# Load necessary packages

library(tidyverse)

# Import data

bigmac <- read_csv("https://mac-stat.github.io/data/bigmac.csv") %>%

rename(income = gross_annual_teacher_income) %>%

select(city, bigmac_mins, income)

# Check it out

head(bigmac)

dim(bigmac)5 Transformations

Announcements etc

SETTLING IN

- Sit in your assigned groups, and catch up.

- Download “05-slr-transformations-notes.qmd”, open it in RStudio, and save it in the “Activities” sub-folder of the “STAT 155” folder.

WRAPPING UP

PP 2 & CP 5 due Thursday

Remember: review first, start early, work with others, ask questions, don’t give your learning over to AI!Quiz 1: next Thursday (9/25)

- structure

- 60 minutes

- taken individually, using pen/pencil & paper

- content

- Unit 1 on Simple Linear Regression, up to and including Thursday’s topic (Categorical predictors)

- you will not need to write R code, but will need to read & interpret R output

- materials

- you can use a 3x5 index card with writing on both sides. These can be handwritten or typed, but you may not include screenshots or share note cards – making your own card is important to the review process. You are required to hand this in with your quiz.

- you cannot use and will not need to use a calculator

- there will be limited opportunities for revision (you can earn up to 50% of missed points back). review syllabus for details.

- check out some study tips in the course manual appendix!

- structure

Upcoming events in MSCS

- Wednesday, 4:40–5:30pm: MSCS Resume Workshop hosted by the MSCS Student Advisory Board + Career Exploration

- Thursday, 11:15-11:45am: MSCS coffee break (OLRI Smail Gallery)

- Thursday, 12:00-1:00pm: MSCS seminar / Puzzle Palooza with Ben Orlin!

- Consider joining the MSCS community listserv (directions here).

- Distinguish between different motivations for transforming variables (e.g. interpretation, regression assumptions).

- Determine when a particular transformation (center, scale, or log) may be appropriate when building a model.

- Interpret regression coefficients after a transformation has taken place.

Required video

Optional

- Reading: Section 3.8.4 in the STAT 155 Notes covers log transformations, and the “ladder of power,” which we will not cover in class.

Warm-up

EXAMPLE 1: Univariate review

Since 1986, The Economist has published “The Big Mac Index” as a metric for comparing purchasing power between cities, giving rise to the phrase Burgernomics. It was developed (sort of jokingly) as a way to explain exchange rates in digestible terms. OPTIONAL: You can read more about the Big Mac index in The Economist.

The bigmac data below, collected in 2006, includes various information on 70 cities:

Included are 3 variables:

citybigmac_mins: average number of minutes of work it takes to afford 1 Big Macincome: the average gross teacher salary in 1 year (USD)

Let’s explore.

# What were the bigmac_mins in New York in 2006?

# Show just these 2 variables.

# Show data on the city that had the smallest bigmac_mins in 2006# Construct and discuss a visualization of bigmac_mins

# Choose a visualization that helps you answer the below question:

# In roughly how many cities were did it take between 50 and 75 minutes to afford a Big Mac?# Calculate the typical bigmac_mins across all cities in 2006

# (What's an appropriate measure here?)

When discussing a visualization for a single variable, remember to comment on:

- central tendency (what’s typical?)

- spread (how much variability is there?)

- shape of the distribution (normal? right-skewed? left-skewed? something else?)

- any outliers

EXAMPLE 2: Modeling intuition

Our goal will be to explore the relationship of bigmac_mins with teacher income, i.e. the extent to which the work time needed to afford a Big Mac in a city might be explained by the average teacher income in that city. What do you expect this to look like? For example, will bigmac_mins increase or decrease as income increases? Will the relationship be linear? Will it be strong?

Check your intuition! Construct and discuss a visualization of bigmac_mins vs income, including a representation of a simple linear regression model of their relationship.

___ %>%

___(___(y = ___, x = ___)) +

geom___() +

geom___(method = ___, se = FALSE)

When discussing a visualization of the relationship between 2+ variables, remember to comment on:

- trend

- strength

- shape

- any outliers

EXAMPLE 3: Modeling review (ON YOUR OWN)

Fit the linear regression model of bigmac_mins vs income:

# Fit the model

bigmac_model_1 <- ___(___, ___)# Get a model summary tableWe already know this is a bad model! Let’s just use it to practice some concepts…

Write out the estimated model formula.

Interpret the

incomecoefficient. Remember: context, units, averages (not individuals), and association (not correlation).Predict the number of minutes it takes to afford a Big Mac in a city with an average teacher income of $4800.

Riga had an average teacher income of $4800 and a “Big Mac time” of 28 minutes. Calculate its residual, i.e. prediction error.

EXAMPLE 4: Model evaluation review (ON YOUR OWN)

1. Is it wrong?

Construct an appropriate evaluative plot of bigmac_model_1. Use it to discuss which of our LINE assumptions (linearity, independence, normality, equal variance) this model appears to violate.

# Residual plot

___ %>%

ggplot(aes(y = ___, x = ___)) +

geom___() +

geom_hline(yintercept = ___)

2. Is it strong?

Answer this question using an appropriate metric, and interpret that metric.

3. Is it fair?

For which cities does this model give poor predictions, hence a misleading conclusion about Big Mac affordability?

NEXT UP: Transformations!

Consider a simple linear regression model:

\[ E(Y | X) = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X \]

In some cases, we may want to transform X, i.e. to model Y vs some function of X:

\[ E(Y | X) = \beta_0 + \beta_1 f(X) \]

NOTE: We may also want to transform Y, but won’t focus on that today!

WHEN SHOULD WE TRANSFORM X?

- Transforming X can improve the interpretability of the model.

For example, we may wish to change the units of measurement on X:- X = height in inches, 2.54 X = height in cm

- X = temperature in Fahrenheit, (X − 32)*5/9 = temperature in Celsius

- Transforming X can sometimes help correct our model when it’s wrong.

- Making our model less wrong, in turn, may make it stronger and/or more fair (by removing bias where the original model is not very effective).

- For example, if changes in our predictor X are more natural to think about in terms of percentages (or multiplicative changes) than raw units, Y vs X may be non-linear but Y vs log(X) may be linear.

- Transforming X for no reason is a bad idea!

Only transform X if it’s relevant to your scientific question / interpretations, and occasionally to handle “correctness” for your model. Excessive transformations can make your model more complicated, with little added benefit.

TYPES OF TRANSFORMATIONS

Location transformations, i.e. centering: \(E[Y | X - a] = \beta_0 + \beta_1 (X - a)\)

Scale transformations: \(E[Y | bX] = \beta_0 + \beta_1 (bX)\)

Location and scale transformations: \(E[Y | b(X - a)] = \beta_0 + \beta_1 (b(X - a))\)

Log transformations: \(E[Y | log(X)] = \beta_0 + \beta_1 (log(X))\)

- In statistics, “log” means “ln” unless otherwise specified.

- We’ll do a deeper review of logs in our logistic regression unit!

Other transformations: \(X^2\), \(\sqrt{X}\), etc

EXAMPLE 5: Transformations

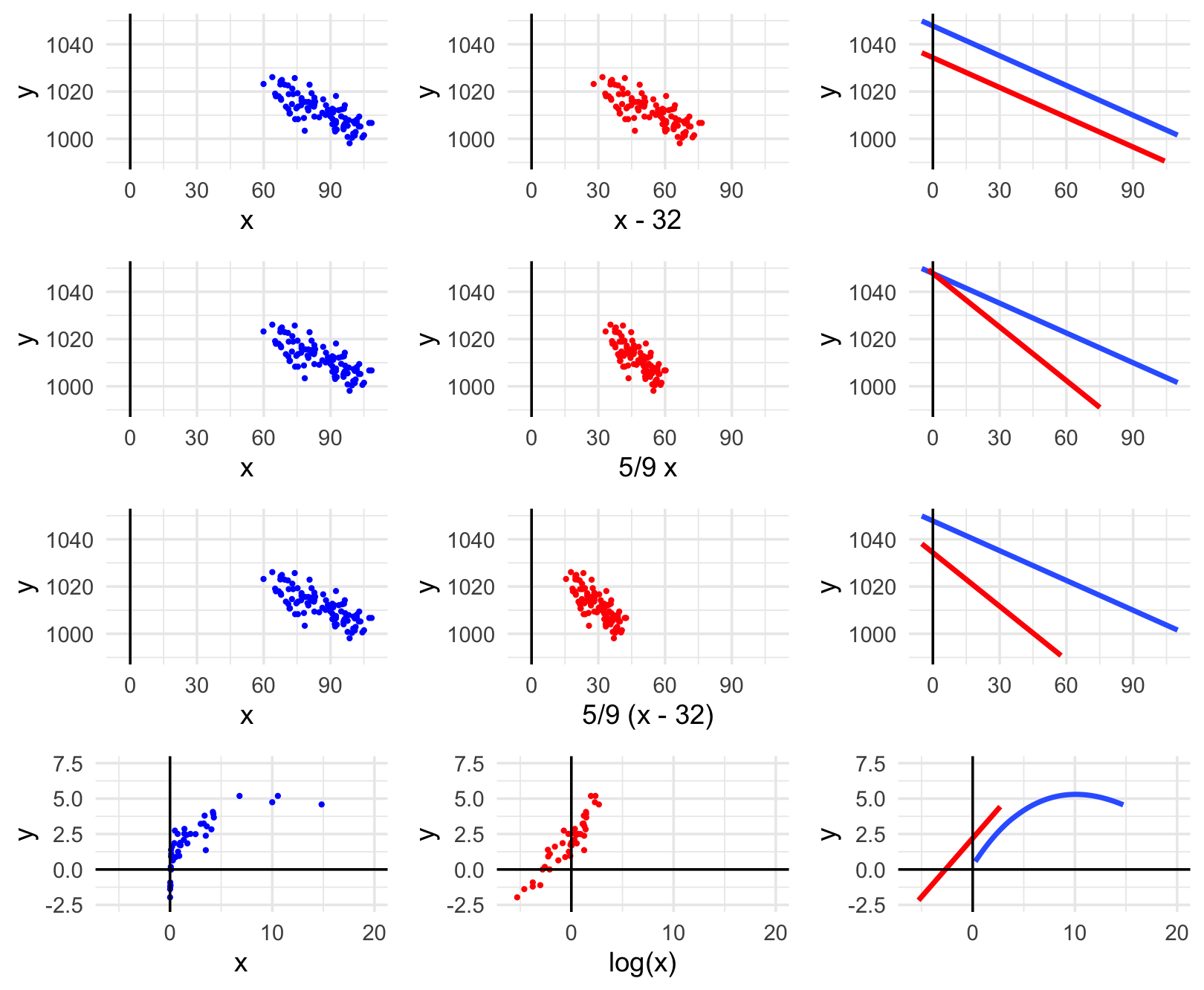

In the image below, each row contains an example of a transformation:

- far left plot = y vs x

- middle plot = y vs transformed x

- right plot = models of y vs x and y vs transformed x on same frame

For each row, indicate how the transformation impacted the point cloud & model.

Row 1 (location transformation): X to X - 32

Row 2 (scale transformation): X to 5/9 X

Row 3 (location & scale transformation): X to 5/9 (X - 32)

Row 4 (log transformation): X to log(X)

\(E[ Y | X ] = \beta_0 + \beta_1 log(X)\)

- Intercept

- \(\beta_0\) = expected value of Y when log(X) = 0

- \(\beta_0\) = expected value of Y when X = 1

- Slope

- \(\beta_1\) = change in the expected value of Y associated with a 1 (logged) unit increase in log(X)

- \(log(1.1) * \beta_1\) is the difference in expected value of Y if we increase X by 10%.

EXAMPLE 6: mutate()

If we want to work with a transformed version of a variable in our dataset, we must define and store this variable using the mutate() function in the tidyverse. You learned about mutate() in PP 1.

# Define a variable called bigmac_hrs that records the BigMac info in hours, not minutes

bigmac %>%

mutate(bigmac_hrs = ___) %>%

head()# If we want to use it later, we should store the bigmac_hrs variable in the bigmac dataset

# DO NOT INCLUDE head() OR WE'LL JUST SAVE 6 ROWS!

bigmac <- bigmac %>%

___# Check our work!

head(bigmac)

dim(bigmac)

Exercises (Required)

Goal

Let’s use visualizations to explore the impact of transforming a predictor variable.

Exercise 1: Transformations can help make our model less wrong

Let’s return to our analysis of bigmac_min vs teacher income. We observed above that this relationship is non-linear, thus a linear regression model of bigmac_min by income would be wrong. Since changes in income are often thought of in terms of percentages than raw units (dollars), we might be able to fix this using a log transform of income:

# Create the log_income and log_bigmac variables

bigmac <- bigmac %>%

mutate(log_income = log(income), log_bigmac = log(bigmac_mins))

head(bigmac)Check out a series of plots:

# bigmac_mins vs income

bigmac %>%

ggplot(aes(y = bigmac_mins, x = income)) +

geom_point()# bigmac_mins vs log_income

bigmac %>%

ggplot(aes(y = bigmac_mins, x = log_income)) +

geom_point()# log_bigmac vs log_income

bigmac %>%

ggplot(aes(y = log_bigmac, x = log_income)) +

geom_point()# log_bigmac vs log_income

# BUT with axis labels on the scale of the original units (not logged units)

# Note that we use the original variables, then log them in the last 2 lines!

bigmac %>%

ggplot(aes(y = bigmac_mins, x = income)) +

geom_point() +

scale_x_continuous(trans = "log") +

scale_y_continuous(trans = "log")FOLLOW-UPS

Which of the following models of Big Mac time by income would be the least “wrong”:

- E[Big Mac time | income] = \(\beta_0\) + \(\beta_1\) income

- E[Big Mac time | log(income)] = \(\beta_0\) + \(\beta_1\) log(income)

- E[log(Big Mac time) | log(income)] = \(\beta_0\) + \(\beta_1\) log(income)

Which of the models above would be the toughest to interpret? (What are the trade-offs between interpretability and “correctness”?)

Exercise 2: Transformations can help make our model easier to interpret

Let’s revisit the High Peaks hiking data with a goal of exploring the relationship of average hiking time in hours with distance (length):

# Import data & check it out

peaks <- read_csv("https://mac-stat.github.io/data/high_peaks.csv")

head(peaks)Part a

Currently, hike length is measured in miles. But suppose we wanted to work with hike length in kilometers, not miles. Since 1 mile is roughly 1.60934 km, this would be a scale transformation. Fill in the code below to define & store length_km in the peaks dataset:

# Define length_km

peaks <- ___ %>%

___(length_km = 1.60934 * length)

# Check it out

peaks %>%

select(time, length, length_km) %>%

head()Part b

Check out some plots of hiking time by distance:

# hiking time vs length in miles

peaks %>%

ggplot(aes(y = time, x = length)) +

geom_point() +

geom_smooth(method = "lm", se = FALSE)# hiking time vs length in km

peaks %>%

ggplot(aes(y = time, x = length_km)) +

geom_point() +

geom_smooth(method = "lm", se = FALSE)# both plots on the same axes

# Don't worry about the code!!

peaks %>%

select(time, length, length_km) %>%

pivot_longer(cols = -time, names_to = "Predictor", values_to = "length") %>%

ggplot(aes(y = time, x = length)) +

geom_point() +

geom_smooth(method = "lm", se = FALSE, fullrange = TRUE) +

facet_wrap(~ Predictor) +

lims(y = c(0, 20), x = c(0, 30))FOLLOW-UP:

What impact did the scale transformation have? Specifically, do these 2 models have the same intercepts? The same slopes?

From an interpretation perspective, you might prefer one model over the other depending on whether you’re more comfortable with miles or kilometers. Mathematically, is one model better than the other? For example, is one less wrong? Is one stronger / have a higher R-squared?

Pause

Choose your own adventure (with your group):

Complete the review Examples 3 and 4 above. If you don’t do this now, you should definitely do it outside of class for extra review!

Do the OPTIONAL exercises below which dig deeper into transformations, exploring how they impact our model formulas and interpretations, not just plots of these models. You’re encouraged but not required to complete these exercises (meaning the concepts are important in general, but won’t be used extensively in this particular course).

Work on PP 2.

Work on CP 5.

Exercises (Optional)

Goal

Let’s explore how center (location), scale, and log transformations of a predictor variable may change our regression models and their interpretations.

Exercise 3: Location transformations (Part 1)

homes includes 2006 data on homes in Saratoga County, New York:

# Import data

homes <- read_csv("https://mac-stat.github.io/data/homes.csv")

head(homes)Our goal is to understand the relationship of home Price ($) with Living.Area, the size of a home in square feet:

homes %>%

ggplot(aes(y = Price, x = Living.Area)) +

geom_point() +

geom_smooth(method = "lm", se = FALSE)Part a

Fit a linear regression model of Price by Living.Area:

# Fit the model

home_mod <- ___(Price ~ Living.Area, ___)

# Display model summary output

___(home_mod)Part b

In context, the intercept indicates that the average price of a 0 square foot home is $13,439.394. Confirm that you agree with this statement and explain why it isn’t meaningful / sensible.

Part c

The issue here is that the “baseline” of home_mod is 0 square foot homes, but the smallest house is 616 square feet (far from 0):

homes %>%

summarize(min(Living.Area))If we want a more meaningful baseline, we can use a location transformation to “start” the Living.Area predictor at a more reasonable value (not 0). Specifically, we can center this predictor at 600 square feet (a more meaningful number than 612 in this context) by defining a new predictor:

Living.Area.Shifted = Living.Area - 600

Fill in the code below define this predictor:

# Define Living.Area.Shifted

homes <- homes %>%

___(Living.Area.Shifted = Living.Area - 600)

# Check it out

homes %>%

select(Price, Living.Area, Living.Area.Shifted) %>%

head()

Exercise 4: Location transformations (Part 2)

Consider a new model that uses the new Living.Area.Shifted predictor:

E[Price | Living.Area.Shifted] = \(\beta_0\) + \(\beta_1\) Living.Area.Shifted

We can interpret the model coefficients as follows:

- \(\beta_0\) = the expected home price when (living area - 600) is 0, i.e. when living area is 600

- \(\beta_1\) = the change in the expected home price associated with a 1 square foot increase in (living area - 600), hence a 1 square foot increase in living area

Part a

Use the above coefficient interpretations and the original home_mod (summarized below) to determine what the new coefficients should be:

- E[Price | Living.Area] = 13439.394 + 113.123 Living.Area

- E[Price | Living.Area.Shifted] = ??? + ??? Living.Area.Shifted

Part b

Check your intuition!

# Fit a model of Price vs. Living.Area.Shifted

# Save this as home_mod_2

home_mod_2 <- lm(Price ~ Living.Area.Shifted, data = homes)

# Display the model summary

summary(home_mod_2)Part c

So we now have 2 models of Price by the size of a home, as measured by Living.Area and Living.Area.Shifted:

- E[Price | Living.Area] = 13439.394 + 113.123 Living.Area

- E[Price | Living.Area.Shifted] = 81312.919 + 113.123 Living.Area.Shifted

As indicated by the equal slopes but differing intercepts, these models simply have different locations:

# Don't worry about the code!!

homes %>%

select(Price, Living.Area, Living.Area.Shifted) %>%

pivot_longer(cols = -Price, names_to = "Predictor", values_to = "Size") %>%

ggplot(aes(y = Price, x = Size)) +

geom_point() +

geom_smooth(method = "lm", se = FALSE) +

facet_wrap(~ Predictor)Importantly, they produce the same predictions! For example, use both models to predict the price of a 1000 square foot home (without using the predict() function). These two predictions should be the same, within rounding.

# Predicting price with the home_mod

13439.394 + 113.123*___

# Predicting price with the home_mod_2

81312.919 + 113.123*___Part d

Suppose we start with the model:

\(E[Y | X] = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X\)

Reflecting on your work above, summarize “rules” for how the intercept and slope are impacted if we perform a location transformation, X - a. (Do these change? If so, how do they change? How does this change depend upon “a”?) Either answer this in words, or by filling in the formula below:

\(E[Y | X - a] = ___ + ___ (X - a)\)

Exercise 5: Scale transformations

Let’s revisit the peaks data. Below is a model of hiking time by length in miles:

peaks_model_1 <- lm(time ~ length, data = peaks)

summary(peaks_model_1)The resulting estimated model formula is below:

E[time | length] = 2.04817 + 0.68427 length

where the length coefficient indicates that a 0.68427 hour increase in the expected hiking time is associated with a 1 mile increase in hike length.

Part a

Recall that in Exercise 2 you performed a scale transformation to define length in kilometers, not miles:

length_km = 1.60934 * length

Suppose then that we modeled time by length_km instead of length:

E[time | length_km] = \(\beta_0\) + \(\beta_1\) length_km

We can interpret the model coefficients as follows:

- \(\beta_0\) = the expected hiking time when

length_kmis 0, hence whenlengthis 0 (sincelength_km = 1.60934 * length) - \(\beta_1\) = the change in the expected hiking time associated with a 1 km increase in length, i.e. a

1/1.60934mile increase in length sincelength_km = 1.60934 * length

Use these interpretations and the original peaks_model_1 (summarized below) to determine what the new coefficients should be:

- E[time | length] = 2.04817 + 0.68427 length

- E[time | length_km] = ??? + ??? length_km

Part b

Check your intuition!

# Fit a model of time vs length_km

peaks_model_2 <- lm(time ~ length_km, data = peaks)

# Display the model summary

summary(peaks_model_2)Part c

So we now have 2 models of average hiking time by hike length, as measured by length and length_km:

- E[time | length] = 2.04817 + 0.68427 length

- E[time | length_km] = 2.04817 + 0.42519 length_km

As indicated by the equal intercepts but differing slopes, these models have the same “location” but differing “scales” hence rates of change:

# Don't worry about the code!!

peaks %>%

select(time, length, length_km) %>%

pivot_longer(cols = -time, names_to = "Predictor", values_to = "length") %>%

ggplot(aes(y = time, x = length)) +

geom_point() +

geom_smooth(method = "lm", se = FALSE, fullrange = TRUE) +

facet_wrap(~ Predictor) +

lims(y = c(0, 20), x = c(0, 30))Importantly, they produce the same predictions! For example, use both models to predict the average hiking time of a 10 mile hike. These two predictions should be the same, within rounding.

# Predicting price with the peaks_model_1

2.04817 + 0.68427*___

# Predicting price with the peaks_model_2

2.04817 + 0.42519*___Part d

Suppose we start with the model:

\(E[Y | X] = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X\)

Reflecting on your work above, summarize “rules” for how the intercept and slope are impacted if we perform a scale transformation, bX. (Do these change? If so, how do they change? How does this change depend upon “b”?) Either answer this in words, or by filling in the formula below:

\(E[Y | bX] = ___ + ___ (bX)\)

Exercise 6: Log transformations

Let’s return to the relationship of bigmac_mins vs teacher income. Recall that this relationship is not linear, thus a linear regression model would be very wrong:

bigmac %>%

ggplot(aes(y = bigmac_mins, x = income)) +

geom_point() +

geom_smooth(method = "lm", se = FALSE)Logging the income predictor helps a bit. The resulting relationship is now linear, though it still has unequal variance:

bigmac %>%

ggplot(aes(y = bigmac_mins, x = log_income)) +

geom_point() +

geom_smooth(method = "lm", se = FALSE)Let’s build and interpret this model:

log_model <- lm(bigmac_mins ~ log_income, data = bigmac)

summary(log_model)The estimated model formula is:

E[bigmac_mins | log_income] = 210.875 - 18.142 log_income

Interpreting these on the logged average income scale isn’t very helpful:

\(210.875\): expected number of minutes it takes to afford 1 Big Mac in cities with a logged average income of 0 dollars

\(-18.142\): for every 1 dollar increase in logged income, we expect the time it takes to afford 1 Big Mac to decrease by 18.142 minutes

CHALLENGE: Utilizing the summary box from the warm-up (after Example 5), translate these interpretations to the income not logged income scale.

Exercise 7: EXTRA OPTIONAL CHALLENGE – logging Y

Above we learned about the impact of logging X. Consider what happens if we log Y (but not X):

\(E[ log(Y) | X ] = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X\)

- Intercept

- \(\beta_0\) = average log(Y) outcome when X = 0

- \(e^{\beta_0}\) = geometric average of Y when X = 0

- Slope

- \(\beta_1\) = change in the average log(Y) outcome associated with a 1-unit increase in X

- \(e^{\beta_1}\) = multiplicative change in the geometric average of Y associated with a 1-unit increase in X

NOTE: The arithmetic average of log(Y) (left) is equivalent to the log of the geometric average of Y (right):

\[ \frac{1}{n}(log(Y_1) + log(Y_2) + \cdots + log(Y_n)) = log\left[\left(Y_1*Y_2* \cdots *Y_n \right)^{1/n} \right] \]

Or in shorthand notation:

\[ \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n log(Y_i) = log\left[\left( \prod_{i=1}^n Y_i\right)^{1/n} \right] \]

Your turn:

- Build and discuss a plot of

log_bigmacvsincome(don’t use the logged income). - Fit a linear regression model of

log_bigmacbyincomeand interpret the coefficient estimates.

Exercise 8: EXTRA OPTIONAL CHALLENGE – proving the impacts of logs

Above, you practiced interpreting coefficients on the logged and unlogged scales when our model includes a log transformation (either for Y or X):

\(E[Y | log(X)] = \beta_0 + \beta_1 log(X)\)

\(E[log(Y) | X] = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X\)

You did so using provided definitions. If you’re curious to prove these definitions, and to explore what happens if we log both Y and X, check out this free resource on the topic.

Reflection

Learning goals

Recall that 2 of the main motivations for transforming X in a regression model of Y vs X are to (1) improve the interpretability of the model (e.g. if we want to change units from km to miles), and (2) to try and correct our model when it’s wrong (i.e. if it doesn’t satisfy the linear regression assumptions). The first motivation is nearly always justified by the scientific context of the research questions you are trying to answer or preferences on how X is recorded (e.g. in km vs miles). The second motivation is a bit more muddy. Now that you have experience, reflect on the earlier comment that “Transforming X for no reason is a bad idea!”. Do you agree / disagree? Why?

Code

What new code did you learn today?

Remember that you’re highly encouraged to start tracking and organizing new code in a cheat sheet (eg: a Google doc).

Solutions

EXAMPLE 1: Context

# Load necessary packages

library(tidyverse)

# Import data

bigmac <- read_csv("https://mac-stat.github.io/data/bigmac.csv") %>%

rename(income = gross_annual_teacher_income) %>%

select(city, bigmac_mins, income)

# Check it out

head(bigmac)

## # A tibble: 6 × 3

## city bigmac_mins income

## <chr> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 Amsterdam 19 41900

## 2 Athens 26 24800

## 3 Auckland 14 31600

## 4 Bangkok 67 3900

## 5 Barcelona 21 33100

## 6 Beijing 44 6000

dim(bigmac)

## [1] 70 3# What were the bigmac_mins in New York in 2006?

# Show just these 2 variables.

bigmac %>%

filter(city == "New York") %>%

select(city, bigmac_mins)

## # A tibble: 1 × 2

## city bigmac_mins

## <chr> <dbl>

## 1 New York 13

# Show data on the city that had the smallest bigmac_mins in 2006

bigmac %>%

filter(bigmac_mins == min(bigmac_mins))

## # A tibble: 1 × 3

## city bigmac_mins income

## <chr> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 Tokyo 10 51900# Construct and discuss a visualization of bigmac_mins

# Choose a visualization that helps you answer the below question:

# In roughly how many cities were did it take between 50 and 75 minutes to afford a Big Mac?

bigmac %>%

ggplot(aes(x = bigmac_mins)) +

geom_histogram()

The minutes it took to afford a Big Mac was right skewed. Whereas many cities had Big Mac times under 25 minutes, it varied greatly from city to city, ranging from ~10 to ~100 minutes.

# Calculate the typical bigmac_mins across all cities in 2006

# (What's an appropriate measure here?)

# Median is appropriate given the right skew

bigmac %>%

summarize(median(bigmac_mins))

## # A tibble: 1 × 1

## `median(bigmac_mins)`

## <dbl>

## 1 25

EXAMPLE 2: Modeling intuition

As annual teacher income gets higher, the time it takes to afford a Big Mac decreases, though the relationship is not linear. Big Mac time is very high when income is below about $10,000 where it sharply decreases. Big Mac time plateaus around ~15-20 minutes in cities with incomes above $20,000.

bigmac %>%

ggplot(aes(y = bigmac_mins, x = income)) +

geom_point() +

geom_smooth(method = "lm", se = FALSE)

EXAMPLE 3: Modeling review

# Fit the model

bigmac_model_1 <- lm(bigmac_mins ~ income, data = bigmac)

# Get a model summary table

summary(bigmac_model_1)

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = bigmac_mins ~ income, data = bigmac)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -29.649 -9.556 -1.784 4.512 43.715

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 5.801e+01 3.104e+00 18.69 < 2e-16 ***

## income -9.092e-04 9.591e-05 -9.48 6.16e-14 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 15.4 on 66 degrees of freedom

## (2 observations deleted due to missingness)

## Multiple R-squared: 0.5766, Adjusted R-squared: 0.5701

## F-statistic: 89.86 on 1 and 66 DF, p-value: 6.164e-14E[bigmac_min | income] = 58.01 - 0.00090923 income

For every 1-dollar increase in average teacher income, the expected time to afford a Big Mac decreases by 0.00090923 minutes. Or for every 1000-dollar increase in average teacher income, the expected time to afford a Big Mac decreases by nearly 1 minute (0.00090923*1000 = 0.90923).

# c

58.01 - 0.00090923*4800

## [1] 53.6457

# d

28 - (58.01 - 0.00090923*4800)

## [1] -25.6457

EXAMPLE 4: Model evaluation review

1. Is it wrong? Yes. The residual plot suggests that the model violates the assumptions of linearity (there’s a curved pattern in the point cloud) and equal variance (the variability in the point cloud increases as the fitted values increase).

# Residual plot

bigmac_model_1 %>%

ggplot(aes(y = .resid, x = .fitted)) +

geom_point() +

geom_hline(yintercept = 0)

2. Is it strong? Moderately. R-squared = 0.5766. That is, the linear model explains roughly 58% of the variability in Big Mac earning times from city to city.

3. Is it fair? The model does worse (the residuals tend to be bigger) for cities with lower teaching incomes (hence higher predicted Big Mac times), thus does not capture reality in those cities.

EXAMPLE 5: Transformations

Row 1 (location transformation): X to X - 32

- shifts the point cloud “left” by 32 units

- shifts the intercept down (not by 32), but slope is the same

Row 2 (scale transformation): X to 5/9 X

- scales the point cloud to a smaller X range

- increases the slope, but intercept is the same

Row 3 (location & scale transformation): X to 5/9 (X - 32)

- shifts the point cloud “left”, and scales the point cloud to a smaller X range

- shifts the intercept down and increases the slope

Row 4 (log transformation): X to log(X)

- straightens out the point cloud and model

EXAMPLE 6: mutate()

# Define a variable called bigmac_hrs that records the BigMac info in hours, not minutes

bigmac %>%

mutate(bigmac_hrs = bigmac_mins / 60) %>%

head()

## # A tibble: 6 × 4

## city bigmac_mins income bigmac_hrs

## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 Amsterdam 19 41900 0.317

## 2 Athens 26 24800 0.433

## 3 Auckland 14 31600 0.233

## 4 Bangkok 67 3900 1.12

## 5 Barcelona 21 33100 0.35

## 6 Beijing 44 6000 0.733

# If we want to use it later, we should store the bigmac_hrs variable in the bigmac dataset

# If we included head() we'd just keep 6 rows!

bigmac <- bigmac %>%

mutate(bigmac_hrs = bigmac_mins / 60)

head(bigmac)

## # A tibble: 6 × 4

## city bigmac_mins income bigmac_hrs

## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 Amsterdam 19 41900 0.317

## 2 Athens 26 24800 0.433

## 3 Auckland 14 31600 0.233

## 4 Bangkok 67 3900 1.12

## 5 Barcelona 21 33100 0.35

## 6 Beijing 44 6000 0.733

dim(bigmac)

## [1] 70 4

Exercise 1: Transformations can help make our model less wrong

# Create the log_income and log_bigmac variables

bigmac <- bigmac %>%

mutate(log_income = log(income), log_bigmac = log(bigmac_mins))

head(bigmac)

## # A tibble: 6 × 6

## city bigmac_mins income bigmac_hrs log_income log_bigmac

## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 Amsterdam 19 41900 0.317 10.6 2.94

## 2 Athens 26 24800 0.433 10.1 3.26

## 3 Auckland 14 31600 0.233 10.4 2.64

## 4 Bangkok 67 3900 1.12 8.27 4.20

## 5 Barcelona 21 33100 0.35 10.4 3.04

## 6 Beijing 44 6000 0.733 8.70 3.78

# bigmac_mins vs income

bigmac %>%

ggplot(aes(y = bigmac_mins, x = income)) +

geom_point()

# bigmac_mins vs log_income

bigmac %>%

ggplot(aes(y = bigmac_mins, x = log_income)) +

geom_point()

# log_bigmac vs log_income

bigmac %>%

ggplot(aes(y = log_bigmac, x = log_income)) +

geom_point()

# log_bigmac vs log_income

# BUT with axis labels on the scale of the original units (not logged units)

# Note that we use the original variables, then log them in the last 2 lines!

bigmac %>%

ggplot(aes(y = bigmac_mins, x = income)) +

geom_point() +

scale_x_continuous(trans = "log") +

scale_y_continuous(trans = "log")

FOLLOW-UP

E[log(Big Mac time) | log(income)] = \(\beta_0\) + \(\beta_1\) log(income)

E[log(Big Mac time) | log(income)] = \(\beta_0\) + \(\beta_1\) log(income). This model is less wrong, but at the expense of interpretability.

Exercise 2: Transformations can help make our model easier to interpret

# Import data & check it out

peaks <- read_csv("https://mac-stat.github.io/data/high_peaks.csv")

head(peaks)

## # A tibble: 6 × 7

## peak elevation difficulty ascent length time rating

## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr>

## 1 Mt. Marcy 5344 5 3166 14.8 10 moderate

## 2 Algonquin Peak 5114 5 2936 9.6 9 moderate

## 3 Mt. Haystack 4960 7 3570 17.8 12 difficult

## 4 Mt. Skylight 4926 7 4265 17.9 15 difficult

## 5 Whiteface Mtn. 4867 4 2535 10.4 8.5 easy

## 6 Dix Mtn. 4857 5 2800 13.2 10 moderatePart a

# Define length_km

peaks <- peaks %>%

mutate(length_km = 1.60934 * length)

# Check it out

peaks %>%

select(time, length, length_km) %>%

head()

## # A tibble: 6 × 3

## time length length_km

## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 10 14.8 23.8

## 2 9 9.6 15.4

## 3 12 17.8 28.6

## 4 15 17.9 28.8

## 5 8.5 10.4 16.7

## 6 10 13.2 21.2Part b

# hiking time vs length in miles

peaks %>%

ggplot(aes(y = time, x = length)) +

geom_point() +

geom_smooth(method = "lm", se = FALSE)

# hiking time vs length in km

peaks %>%

ggplot(aes(y = time, x = length_km)) +

geom_point() +

geom_smooth(method = "lm", se = FALSE)

# both plots on the same axes

# Don't worry about the code!!

peaks %>%

select(time, length, length_km) %>%

pivot_longer(cols = -time, names_to = "Predictor", values_to = "length") %>%

ggplot(aes(y = time, x = length)) +

geom_point() +

geom_smooth(method = "lm", se = FALSE, fullrange = TRUE) +

facet_wrap(~ Predictor) +

lims(y = c(0, 20), x = c(0, 30))

FOLLOW-UP:

- Same intercepts, different slopes.

- The quality of these models is the same! They’d have the same R-squared, make the same predictions, etc.

Exercise 3: Location transformations (Part 1)

# Import data

homes <- read_csv("https://mac-stat.github.io/data/homes.csv")

head(homes)

## # A tibble: 6 × 16

## Price Lot.Size Waterfront Age Land.Value New.Construct Central.Air

## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 132500 0.09 0 42 50000 0 0

## 2 181115 0.92 0 0 22300 0 0

## 3 109000 0.19 0 133 7300 0 0

## 4 155000 0.41 0 13 18700 0 0

## 5 86060 0.11 0 0 15000 1 1

## 6 120000 0.68 0 31 14000 0 0

## # ℹ 9 more variables: Fuel.Type <dbl>, Heat.Type <dbl>, Sewer.Type <dbl>,

## # Living.Area <dbl>, Pct.College <dbl>, Bedrooms <dbl>, Fireplaces <dbl>,

## # Bathrooms <dbl>, Rooms <dbl>

homes %>%

ggplot(aes(y = Price, x = Living.Area)) +

geom_point() +

geom_smooth(method = "lm", se = FALSE)

Part a

# Fit the model

home_mod <- lm(Price ~ Living.Area, data = homes)

# Display model summary output

summary(home_mod)

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = Price ~ Living.Area, data = homes)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -277022 -39371 -7726 28350 553325

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 13439.394 4992.353 2.692 0.00717 **

## Living.Area 113.123 2.682 42.173 < 2e-16 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 69100 on 1726 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.5075, Adjusted R-squared: 0.5072

## F-statistic: 1779 on 1 and 1726 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16Part b

A 0 square foot home doesn’t exist!

Part c

homes %>%

summarize(min(Living.Area))

## # A tibble: 1 × 1

## `min(Living.Area)`

## <dbl>

## 1 616

# Define Living.Area.Shifted

homes <- homes %>%

mutate(Living.Area.Shifted = Living.Area - 600)

# Check it out

homes %>%

select(Price, Living.Area, Living.Area.Shifted) %>%

head()

## # A tibble: 6 × 3

## Price Living.Area Living.Area.Shifted

## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 132500 906 306

## 2 181115 1953 1353

## 3 109000 1944 1344

## 4 155000 1944 1344

## 5 86060 840 240

## 6 120000 1152 552

Exercise 4: Location transformations (Part 2)

Part a

- E[Price | Living.Area] = 13439.394 + 113.123 Living.Area

- E[Price | Living.Area.Shifted] = 81312.89 + 113.123 Living.Area.Shifted

Why?

- The intercept represents the average house price when

Living.Area.Shiftedis 0, i.e.Living.Areais 600 square feet. From the originalhome_mod, we can calculate the expected price for 600 square foot homes: 13439.394 + (113.123*600) = 81312.89. - The slope in this model represents the average price change for each unit change in

Living.Area.Shifted(which is the same as a unit change inLiving.Area). Based on this, the slope should be the same as inhome_mod($113.12 per square foot).

Part b

Our intuition was correct, within rounding.

# Fit a model of Price vs. Living.Area.Shifted

# Save this as home_mod_2

home_mod_2 <- lm(Price ~ Living.Area.Shifted, data = homes)

# Display the model summary

summary(home_mod_2)

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = Price ~ Living.Area.Shifted, data = homes)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -277022 -39371 -7726 28350 553325

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 81312.919 3515.879 23.13 <2e-16 ***

## Living.Area.Shifted 113.123 2.682 42.17 <2e-16 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 69100 on 1726 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.5075, Adjusted R-squared: 0.5072

## F-statistic: 1779 on 1 and 1726 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16Part c

# Predicting price with the home_mod

13439.394 + 113.123*1000

## [1] 126562.4

# Predicting price with the home_mod_2

81312.919 + 113.123*(1000 - 600)

## [1] 126562.1Part d

- The slope is the same (increasing X - a by 1 unit is the same as increasing X by 1 unit).

- The intercept shifts, the new intercept being \(\beta_0 + a \beta_1\) (i.e. the expected Y when X - a is 0, hence X = a).

\(E[Y | X - a] = [\beta_0 + a \beta_1] + \beta_1 (X - a)\)

Exercise 5: Scale transformations

peaks_model_1 <- lm(time ~ length_miles, data = peaks)

## Error in eval(predvars, data, env): object 'length_miles' not found

summary(peaks_model_1)

## Error: object 'peaks_model_1' not foundPart a

- E[time | length_miles] = 2.04817 + 0.68427 length_miles

- E[time | length_km] = 2.04817 + 0.4251867 length_km

Why?

- The intercept represents the average hiking time when

length_kmis 0, hence whenlength_milesis 0. Thus the intercept is the same as in the original model, from which we know that the average hiking time whenlength_milesis 0 is 2.04817 hours. - The slope in this model represents the average change in hiking time for each 1-km increase in

length_km, which is the same as a (1/1.60934)-unit change inlength_miles(since 1 km = (1/1.60934) miles). Based on this, the slope should be 0.68427*(1 / 1.60934) = 0.4251867.

Part b

# Fit a model of time vs length_km

peaks_model_2 <- lm(time ~ length_km, data = peaks)

# Display the model summary

summary(peaks_model_2)

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = time ~ length_km, data = peaks)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -2.4491 -0.6687 -0.0122 0.5590 4.0034

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 2.04817 0.80371 2.548 0.0144 *

## length_km 0.42519 0.03829 11.105 2.39e-14 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 1.449 on 44 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.737, Adjusted R-squared: 0.7311

## F-statistic: 123.3 on 1 and 44 DF, p-value: 2.39e-14Part c

# Don't worry about the code!!

peaks %>%

select(time, length_miles, length_km) %>%

pivot_longer(cols = -time, names_to = "Predictor", values_to = "length") %>%

ggplot(aes(y = time, x = length)) +

geom_point() +

geom_smooth(method = "lm", se = FALSE, fullrange = TRUE) +

facet_wrap(~ Predictor) +

lims(y = c(0, 20), x = c(0, 30))

## Error in `select()`:

## ! Can't select columns that don't exist.

## ✖ Column `length_miles` doesn't exist.

# Predicting price with the peaks_model_1

2.04817 + 0.68427*10

## [1] 8.89087

# Predicting price with the peaks_model_2

2.04817 + 0.42519*(10*1.60934)

## [1] 8.890923Part d

- The intercept is the same. bX = 0 when X = 0.

- The slope changes to \(\beta_1 / b\) since a 1-unit increase in bX is equivalent to a (1/b)-unit increase in X.

\(E[Y | bX] = \beta_0 + (\beta_1/b) (bX)\)

Exercise 6: Log transformations

bigmac %>%

ggplot(aes(y = bigmac_mins, x = income)) +

geom_point() +

geom_smooth(method = "lm", se = FALSE)

bigmac %>%

ggplot(aes(y = bigmac_mins, x = log_income)) +

geom_point() +

geom_smooth(method = "lm", se = FALSE)

log_model <- lm(bigmac_mins ~ log_income, data = bigmac)

summary(log_model)

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = bigmac_mins ~ log_income, data = bigmac)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -36.817 -6.951 -1.241 6.032 41.357

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 210.875 14.687 14.36 <2e-16 ***

## log_income -18.142 1.502 -12.08 <2e-16 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 13.21 on 66 degrees of freedom

## (2 observations deleted due to missingness)

## Multiple R-squared: 0.6886, Adjusted R-squared: 0.6838

## F-statistic: 145.9 on 1 and 66 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16\(210.875\): expected number of minutes it takes to earn 1 Big Mac in cities with an average income of 1 dollar (X = 1 when log(X) = 0))

\(log(1.1)*(-18.142) = -1.73\): for every 10% increase in income, the expected time it takes to earn 1 Big Mac to decrease by 1.73 minutes.

log(1.1)*(-18.142)WHY? Suppose we have two salaries: Salary1 and Salary2. If Salary2 is 10% higher than Salary1, then Salary2/Salary1 = 1.1. It is a property of logarithms that log(Salary2/Salary1) = log(Salary2) - log(Salary1). In this case log(Salary2/Salary1) = log(Salary2) - log(Salary1) = log(1.1) = 0.09531018. So a 10% increase in salary is a 0.09 unit increase in the log scale. Thus, while a 1 unit increase in log salary is associated with an average decrease of 18 Big Mac minutes, a 0.0953 unit increase in log salary (which corresponds to a 10% multiplicative increase), is associated with a 1.7 minute decrease in Big Mac minutes:

# Multiplicative difference of 1.1, or 10% between salaries gives us the

log(1.1) * -18.142

## [1] -1.729117

Exercise 7: EXTRA OPTIONAL CHALLENGE – logging Y

bigmac %>%

ggplot(aes(y = log_bigmac, x = income)) +

geom_point() +

geom_smooth(method = "lm", se = FALSE)

new_bigmac_model <- lm(log_bigmac ~ income, bigmac)

summary(new_bigmac_model)

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = log_bigmac ~ income, data = bigmac)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -0.71669 -0.23163 -0.03674 0.18606 0.67940

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 4.035e+00 6.703e-02 60.19 <2e-16 ***

## income -2.684e-05 2.072e-06 -12.96 <2e-16 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 0.3326 on 66 degrees of freedom

## (2 observations deleted due to missingness)

## Multiple R-squared: 0.7178, Adjusted R-squared: 0.7135

## F-statistic: 167.9 on 1 and 66 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

exp(4.035)

## [1] 56.54292

exp(-0.00002684)

## [1] 0.9999732E[log_bigmac | income] = 4.035 - 0.00002684 income

- Intercept: For cities with an average income of 0 (which doesn’t exist)…

- the average logged Big Mac earning time is 4.035 minutes; equivalently,

- the geometric average Big Mac earning time is 56.5 minutes (\(e^4.035 = 56.5\)).

- Slope: When average income increases by 1 dollar…

- the average logged Big Mac earning time drops by 0.00002684 minute; equivalently,

- the geometric average Big Mac earning time multiples by a factor of 0.9999732 (\(e^{-0.00002684} = 0.9999732\)), i.e. it’s 99.99732% as high

Exercise 8: EXTRA OPTIONAL CHALLENGE – proving the impacts of logs

Check out the resource!