library(tidyverse)

titanic <- read_csv("https://mac-stat.github.io/data/titanic.csv") %>%

mutate(Survived = as.factor(Survived)) %>%

filter(!is.na(PClass))

head(titanic)

## # A tibble: 6 × 5

## Name PClass Age Sex Survived

## <chr> <chr> <dbl> <chr> <fct>

## 1 Allen, Miss Elisabeth Walton 1st 29 female 1

## 2 Allison, Miss Helen Loraine 1st 2 female 0

## 3 Allison, Mr Hudson Joshua Creighton 1st 30 male 0

## 4 Allison, Mrs Hudson JC (Bessie Waldo Daniels) 1st 25 female 0

## 5 Allison, Master Hudson Trevor 1st 0.92 male 1

## 6 Anderson, Mr Harry 1st 47 male 112 Simple logistic regression

Announcements etc

SETTLING IN

- Today is a paper day! Put away laptops. You’ll need a basic calculator (possibly on your phone) that can calculate \(\log(x)\) and \(e^x = \text{exp}(x)\).

- After class, you can find the qmd here: “12-logistic-univariate-notes.qmd”.

WRAPPING UP

- Type up your notes in the qmd! This will be a good way to study.

- Today: PP 4 due

- Thursday: Fall break! There is nothing to do / think about for this class over break.

- After Fall break:

- Tuesday = CP 11 (You’re encouraged to do this Monday, not over break.)

- Thursday = PP 5

- Thursday, Oct 30 = Quiz 2

This will focus on the Multiple Linear Regression and Logistic Regression units, but is naturally cumulative.

- Distinguish between probabilities and odds, and convert one to the other

- Explain the differences between linear regression and logistic regression for modeling binary outcomes

- Explore simple logistic regression models

- visualize relationships

- build models in R

- interpret coefficients

- make predictions

- converting from log odds to odds to probability scales

References

Logistic Regression

Let \(Y\) be a binary categorical response variable:

\[Y = \begin{cases} 1 & \; \text{ if event happens} \\ 0 & \; \text{ if event doesn't happen} \\ \end{cases}\]

Further define

\[\begin{split} p &= \text{ probability event happens} \\ 1-p &= \text{ probability event doesn't happen} \\ \text{odds} & = \text{ odds event happens} = \frac{p}{1-p} \\ \end{split}\]

Then a logistic regression model of \(Y\) by \(x\) is \[\log(\text{odds}) = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X\]

We can transform this to get (curved) models of odds and probability:

\[\begin{split} \text{odds} & = e^{\beta_0 + \beta_1 X} \\ p & = \frac{\text{odds}}{\text{odds}+1} = \frac{e^{\beta_0 + \beta_1 X}}{e^{\beta_0 + \beta_1 X}+1} \\ \end{split}\]

Warm-up

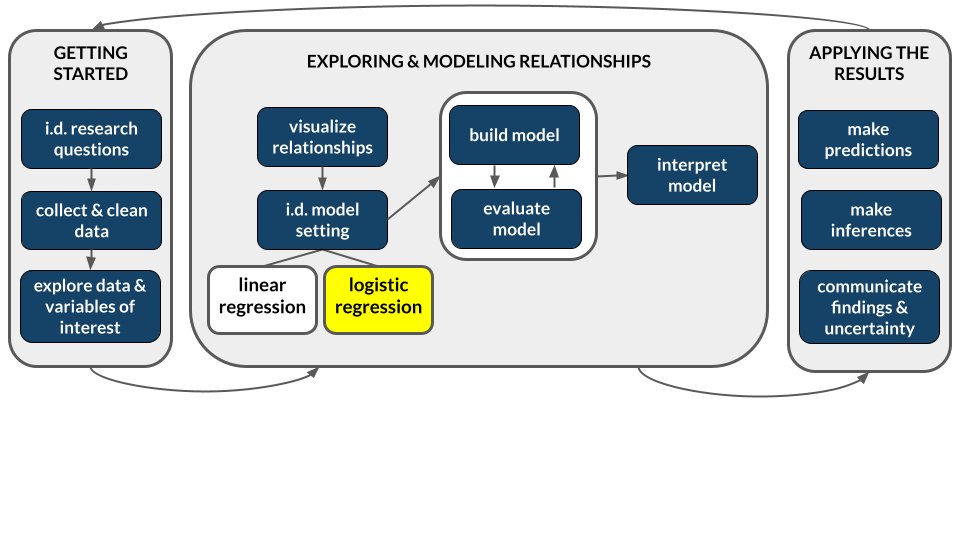

We’ve been focusing on “Normal” linear regression models for quantitative response variables Y. But not all response variables are quantitative! We’ll now explore logistic regression models for binary categorical response variables Y. This dramatically expands the types of relationships we’re able to explore. Though the details of our models will change, the spirit and considerations are the same:

- we want to learn about Y from predictors X

- we want to build, interpret, and evaluate our models

- we need to be mindful of multicollinearity, overfitting, etc in this process

EXAMPLE 1: Normal or logistic?

For each scenario below, indicate whether “Normal” or logistic regression would be the appropriate modeling tool.

We want to model a person’s commute time (Y) by their distance to work (X).

We want to model a person’s commute time (Y) by whether or not they take public transit (X).

We want to model whether or not a person gets a speeding ticket (Y) based on their driving speed (X).

EXAMPLE 2: probability vs odds vs log(odds)

- There’s a 0.9 probability that your team wins its next game. Calculate the corresponding odds and log(odds) of this event. NOTE:

log()is the natural log function in RStudio.

- The log(odds) that your bus is late are -1.0986. Calculate the corresponding odds and probability of this event. NOTE: Use

exp().

EXAMPLE 3: Conditional odds

The Titanic was a British passenger ship that famously sank in 1912 after hitting an iceberg in the North Atlantic Ocean. Approximately 2200 passengers were on board, and it’s estimated that 1500 did not survive the crash. The titanic dataset has info on a sample of these passengers:

Let’s use it to explore the relationship of:

- Y =

Survived(1 = survived, 0 = did not survive) - X =

PClass(ticket class = 1st, 2nd, 3rd)

To this end, check out some tables of counts:

titanic %>%

count(PClass, Survived)

## # A tibble: 6 × 3

## PClass Survived n

## <chr> <fct> <int>

## 1 1st 0 129

## 2 1st 1 193

## 3 2nd 0 160

## 4 2nd 1 119

## 5 3rd 0 573

## 6 3rd 1 138

library(janitor)

titanic %>%

tabyl(PClass, Survived) %>%

adorn_totals(c("row", "col"))

## PClass 0 1 Total

## 1st 129 193 322

## 2nd 160 119 279

## 3rd 573 138 711

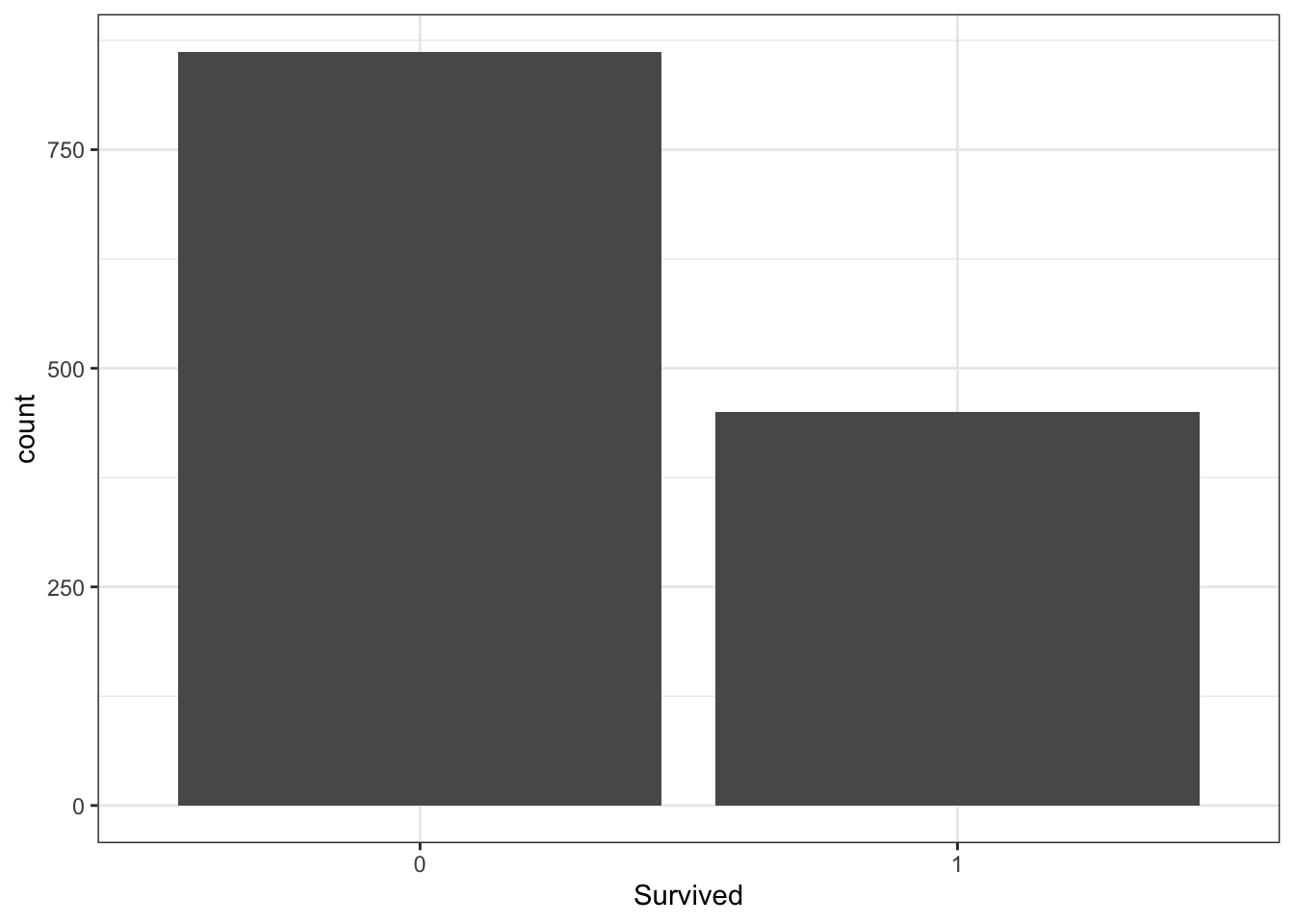

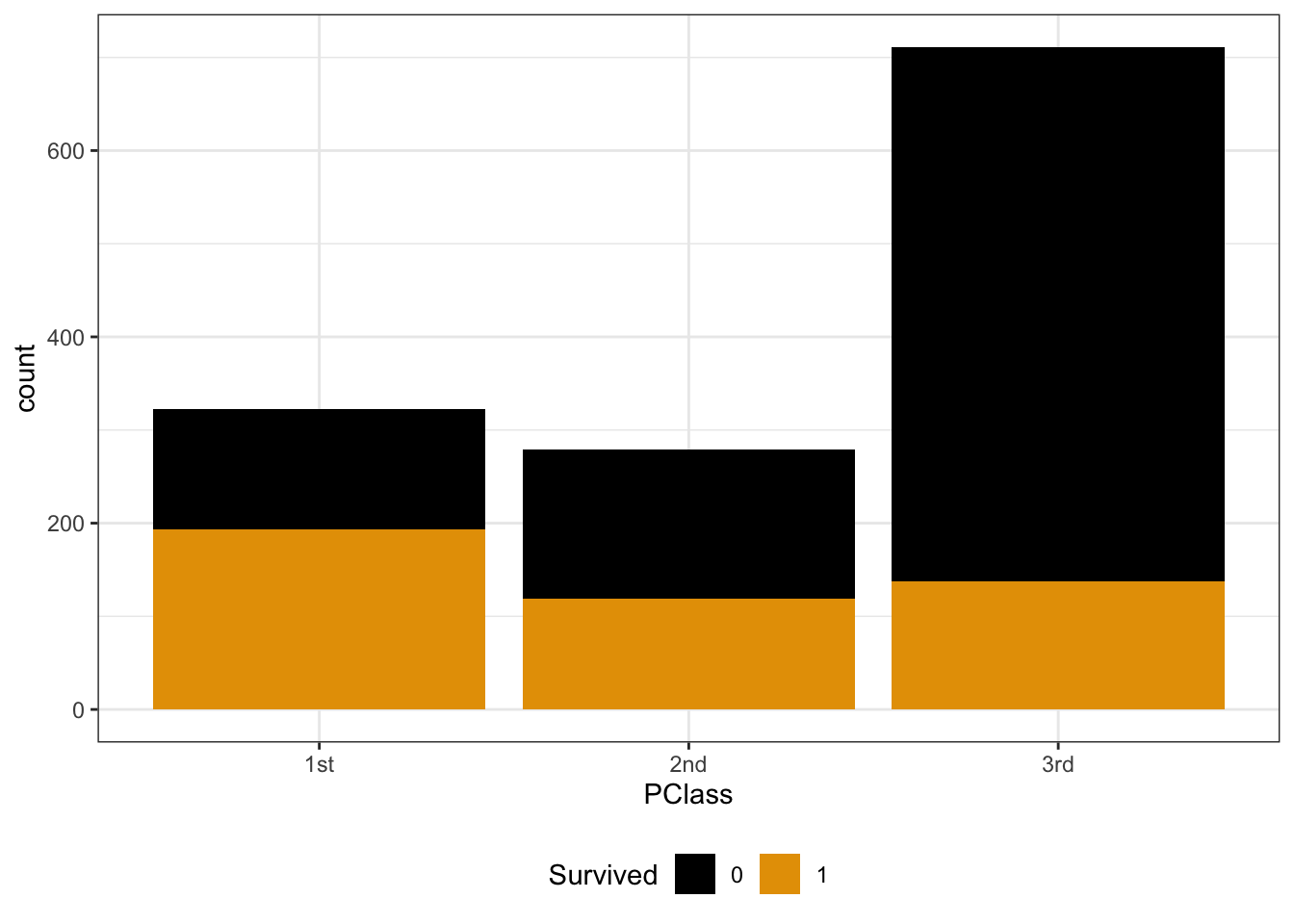

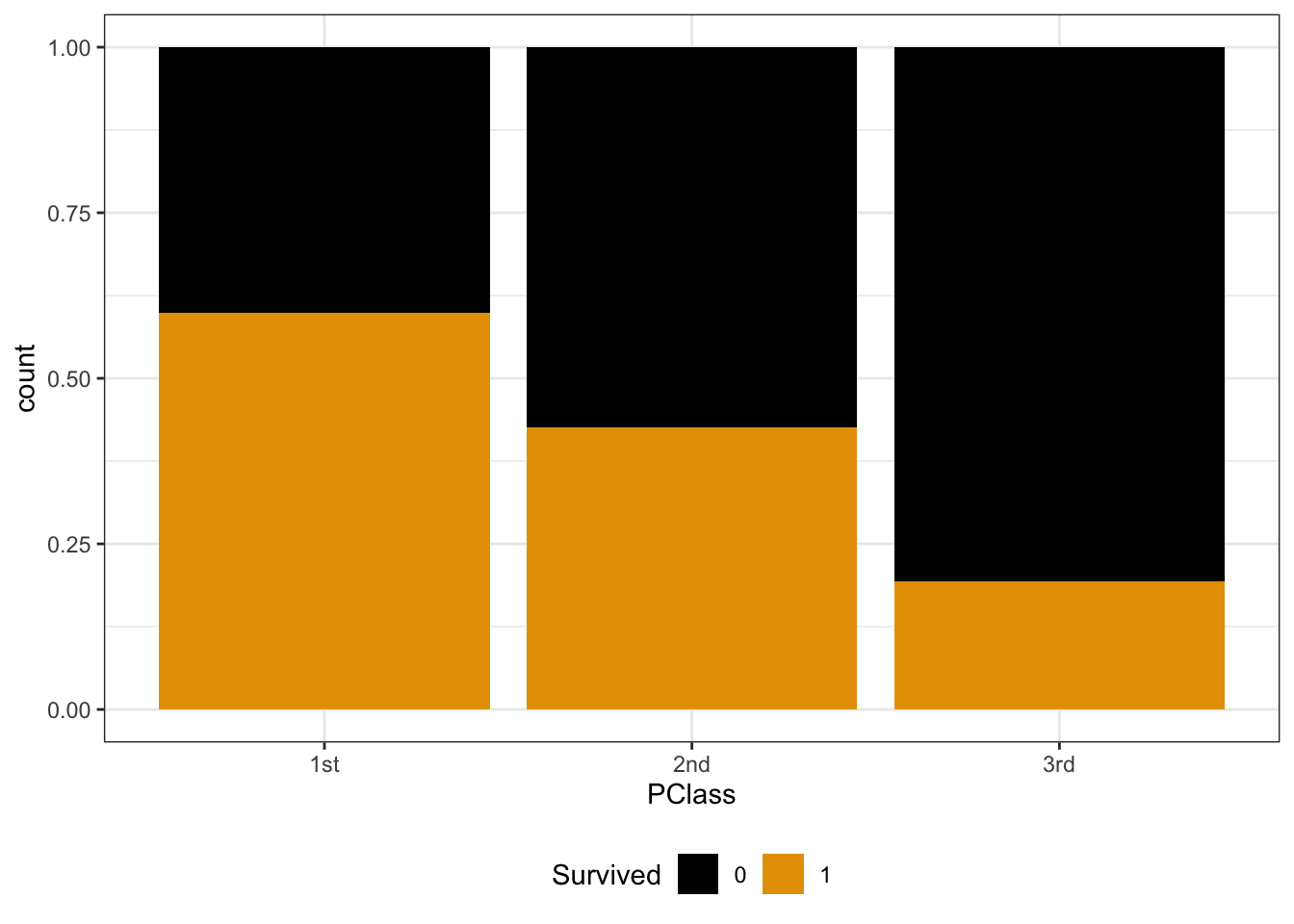

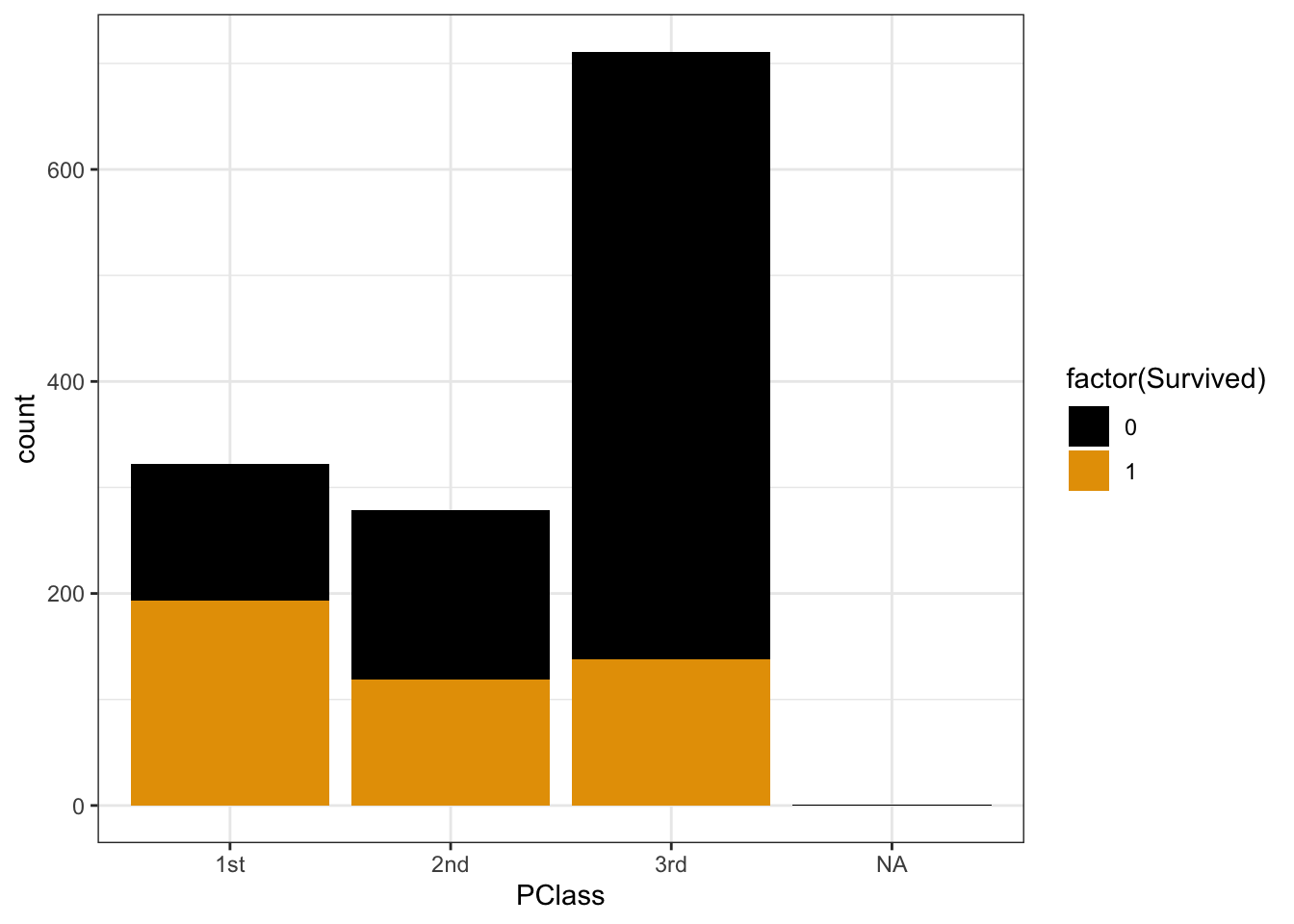

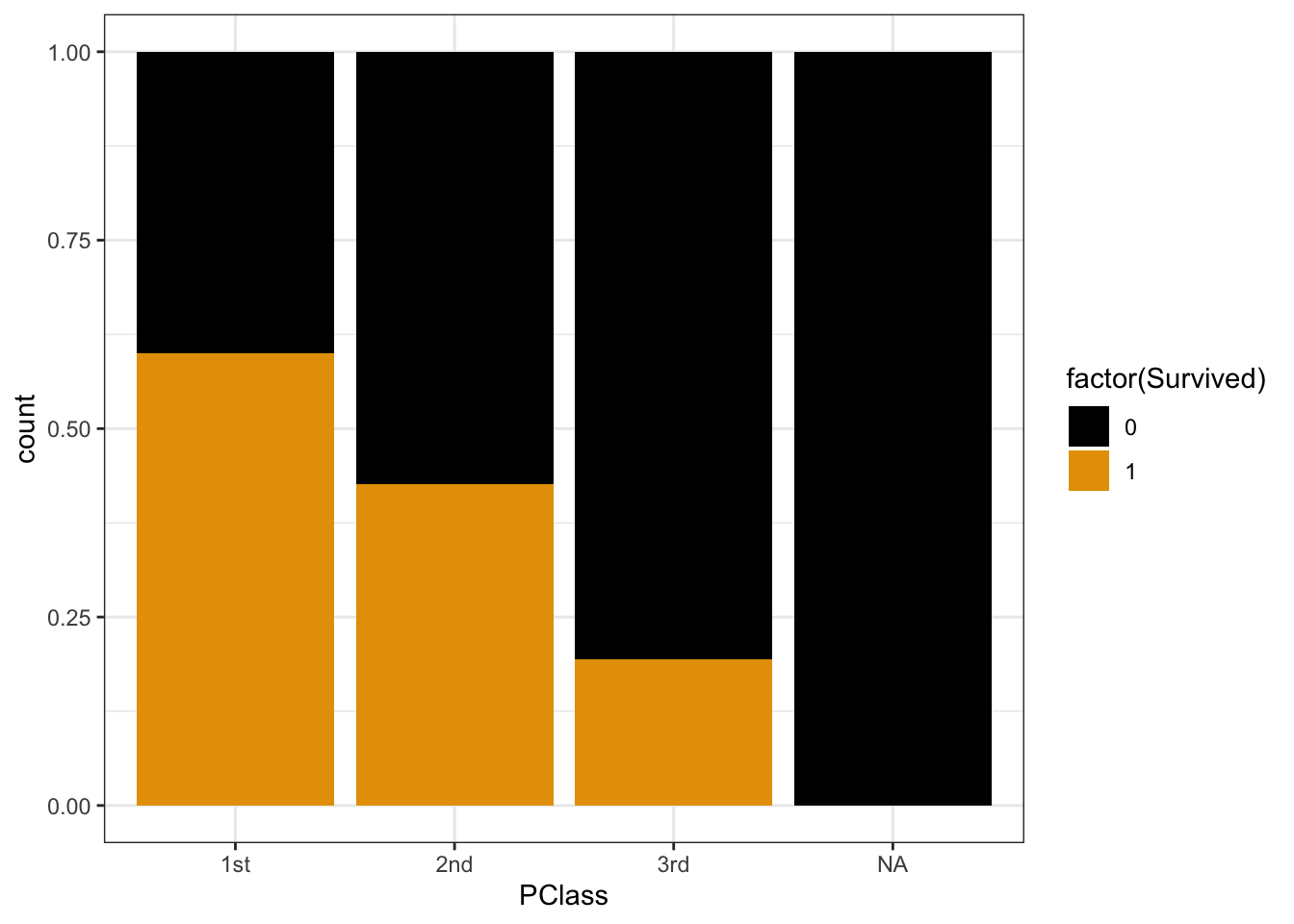

## Total 862 450 1312And a plot of Y alone, and 2 plots of Y with X.

titanic %>%

ggplot(aes(x = Survived)) +

geom_bar() +

theme_bw()

titanic %>%

ggplot(aes(x = PClass, fill = Survived)) +

geom_bar() +

theme_bw() +

theme(legend.position = "bottom")

titanic %>%

ggplot(aes(x = PClass, fill = Survived)) +

geom_bar(position = "fill") +

theme_bw() +

theme(legend.position = "bottom")

Calculate the overall odds that a passenger survived. (Which plot provides insight here?)

Y and X are both categorical. To visualize their relationship, we can make bar plots of X, split up by category of Y. Use plots 2 & 3 to describe the relationship of survival with ticket class. (What’s the difference between these plots, and which plot makes it easier to answer this question?!)

How does Y depend upon X? Calculate the conditional odds that a 1st class passenger survived, i.e. the odds of survival conditioned on the passenger being 1st class: Odds(survive | 1st class)

Calculate the conditional odds that a 3rd class passenger survived: Odds(survive | 3rd class)

EXAMPLE 4: Odds ratios

Models help us compare the behavior of Y for different possible X values. In logistic regression, these comparisons are often measured by odds ratios, a ratio of odds (unsurprisingly) that compares the odds of one group to another.

Calculate & interpret the odds ratio of surviving the Titanic, comparing those in the 1st class to those in the 3rd class.

Calculate & interpret the odds ratio of surviving the Titanic, comparing those in the 3rd class to those in the 1st class.

Let “odds for group A” be the conditional odds of an event for some group A. Let “odds for group B” be the conditional odds of an event for some group B. Then the odds ratio (OR) of the event, comparing group A to group B is

OR = (odds for group A) / (odds for group B)

Then OR >= 0 where:

If OR > 1, then the odds of the event are higher for group A than group B. Examples:

- OR = 2: The odds of the event are 2 times higher (100% higher) for group A than group B.

- OR = 1.5: The odds of the event are one and a half times higher (50% higher) for group A than group B.

If OR = 1, then the odds of the event are the same for groups A and B.

If OR < 1, then the odds of the event are lower for group A than group B. Examples:

- OR = 0.5: The odds of the event are half as high (50% as high) for group A than group B.

- OR = 0.2:

- The odds of the event for group A are 0.2 times (20% as high as) the odds for group B.

- The odds of the event are 80% lower for group A than group B.

Exercises

Directions

There’s a lot of new and specialized syntax today. Peak at but not get distracted by the syntax – stay focused on the bigger picture concepts.

The story

The climbers data is sub-sample of the Himalayan Database distributed through the R for Data Science TidyTuesday project. This dataset includes information on the results and conditions for various Himalayan climbing expeditions. Each row corresponds to a single member of a climbing expedition team:

# Load packages and data

library(tidyverse)

climbers <- read_csv("https://mac-stat.github.io/data/climbers_sub.csv") %>%

select(peak_name, success, age, oxygen_used, height_metres)

# Check out the first 6 rows

head(climbers)

## # A tibble: 6 × 5

## peak_name success age oxygen_used height_metres

## <chr> <lgl> <dbl> <lgl> <dbl>

## 1 Ama Dablam TRUE 28 FALSE 6814

## 2 Ama Dablam TRUE 27 FALSE 6814

## 3 Ama Dablam TRUE 35 FALSE 6814

## 4 Ama Dablam TRUE 37 FALSE 6814

## 5 Ama Dablam TRUE 43 FALSE 6814

## 6 Ama Dablam FALSE 38 FALSE 6814Our goal will be to model whether or not a climber has success (Y) by their age (in years) or oxygen_used (TRUE or FALSE). Since success is a binary categorical variable, i.e. a climber is either successful or they’re not, we’ll utilize logistic regression.

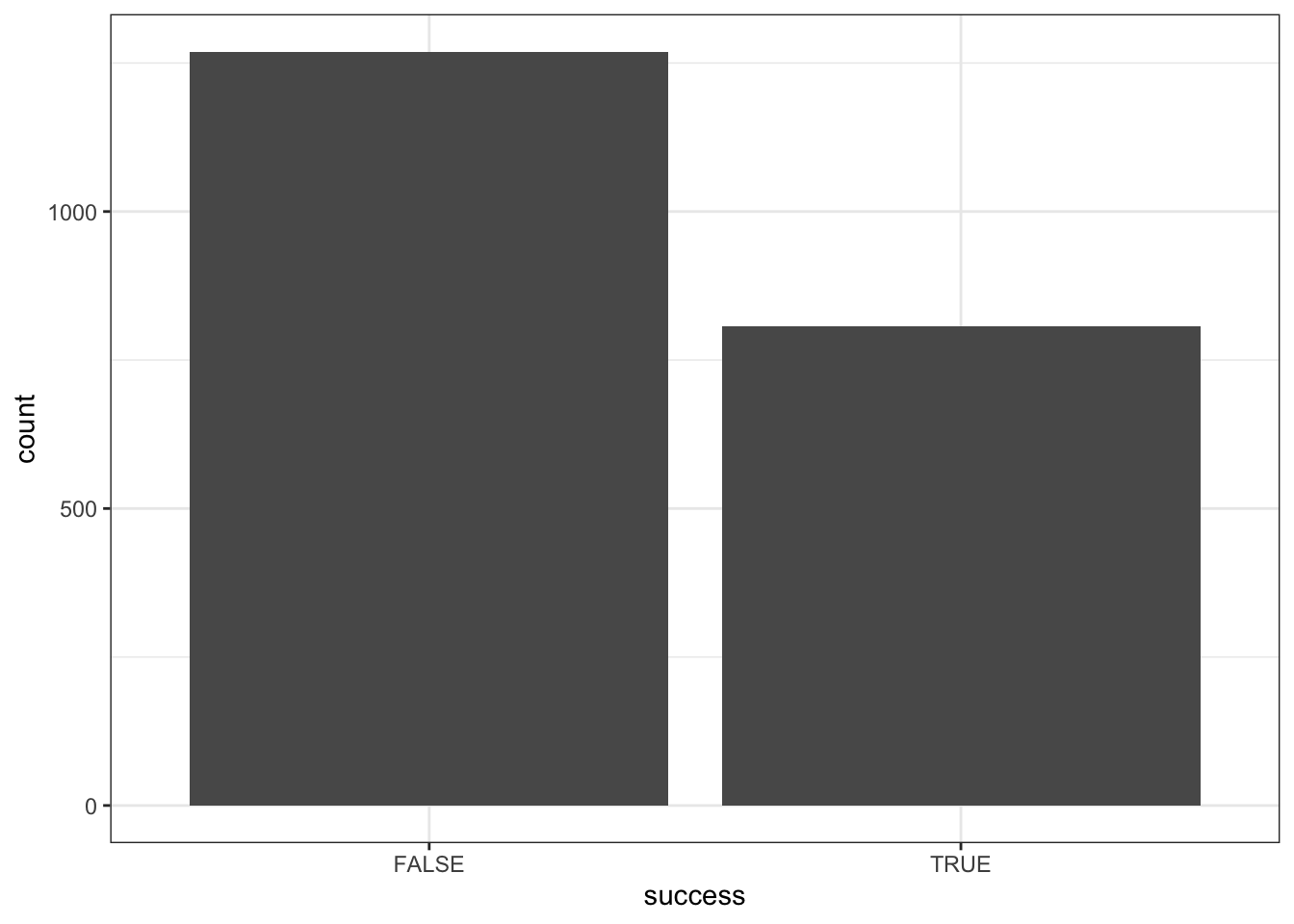

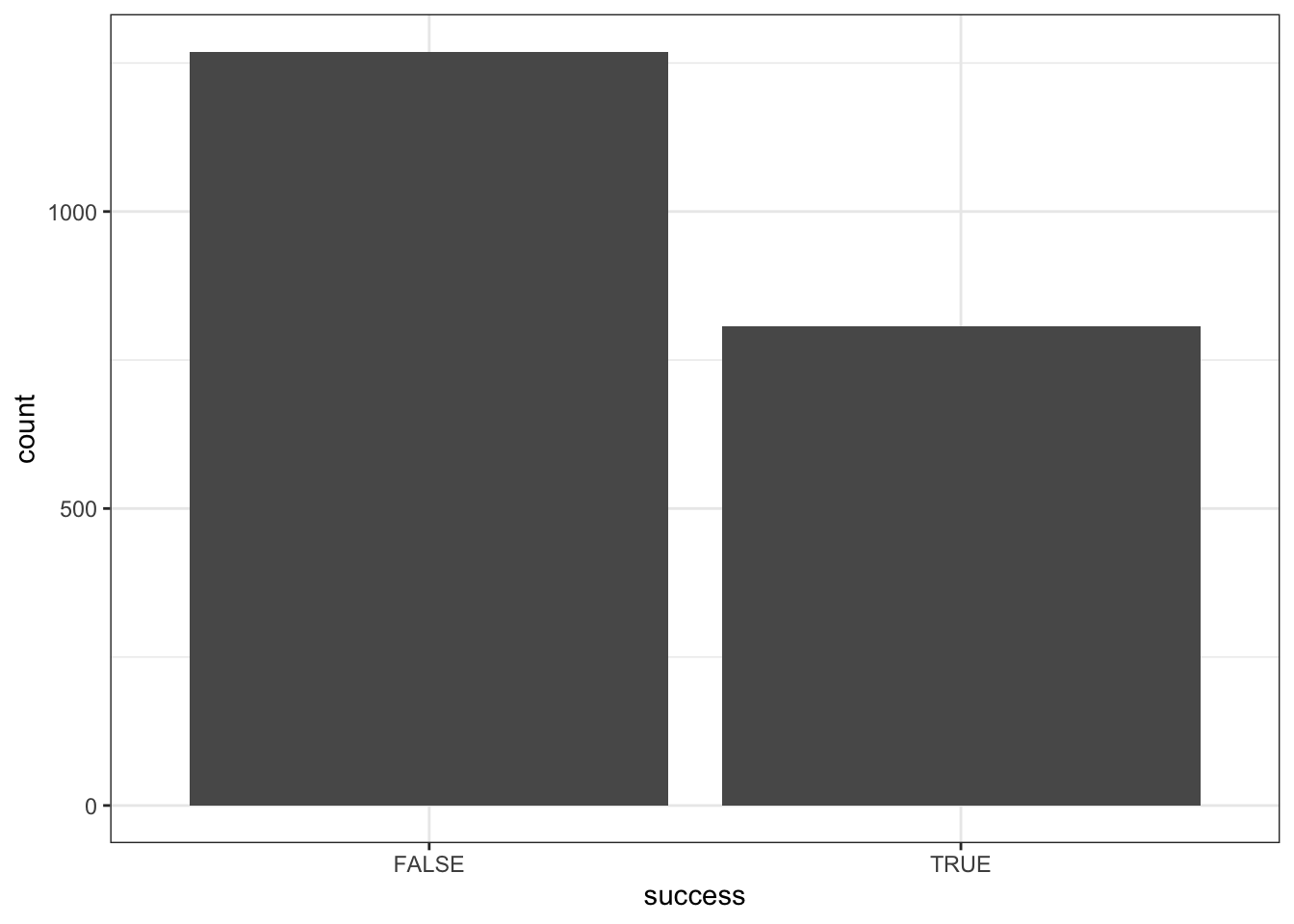

Exercise 1: Getting to know Y

Our response variable Y, success, is binary (hence categorical). Thus we can explore Y alone using a bar plot and table of counts. Discuss what you learn here.

climbers %>%

count(success)

## # A tibble: 2 × 2

## success n

## <lgl> <int>

## 1 FALSE 1269

## 2 TRUE 807

climbers %>%

ggplot(aes(x = success)) +

geom_bar()

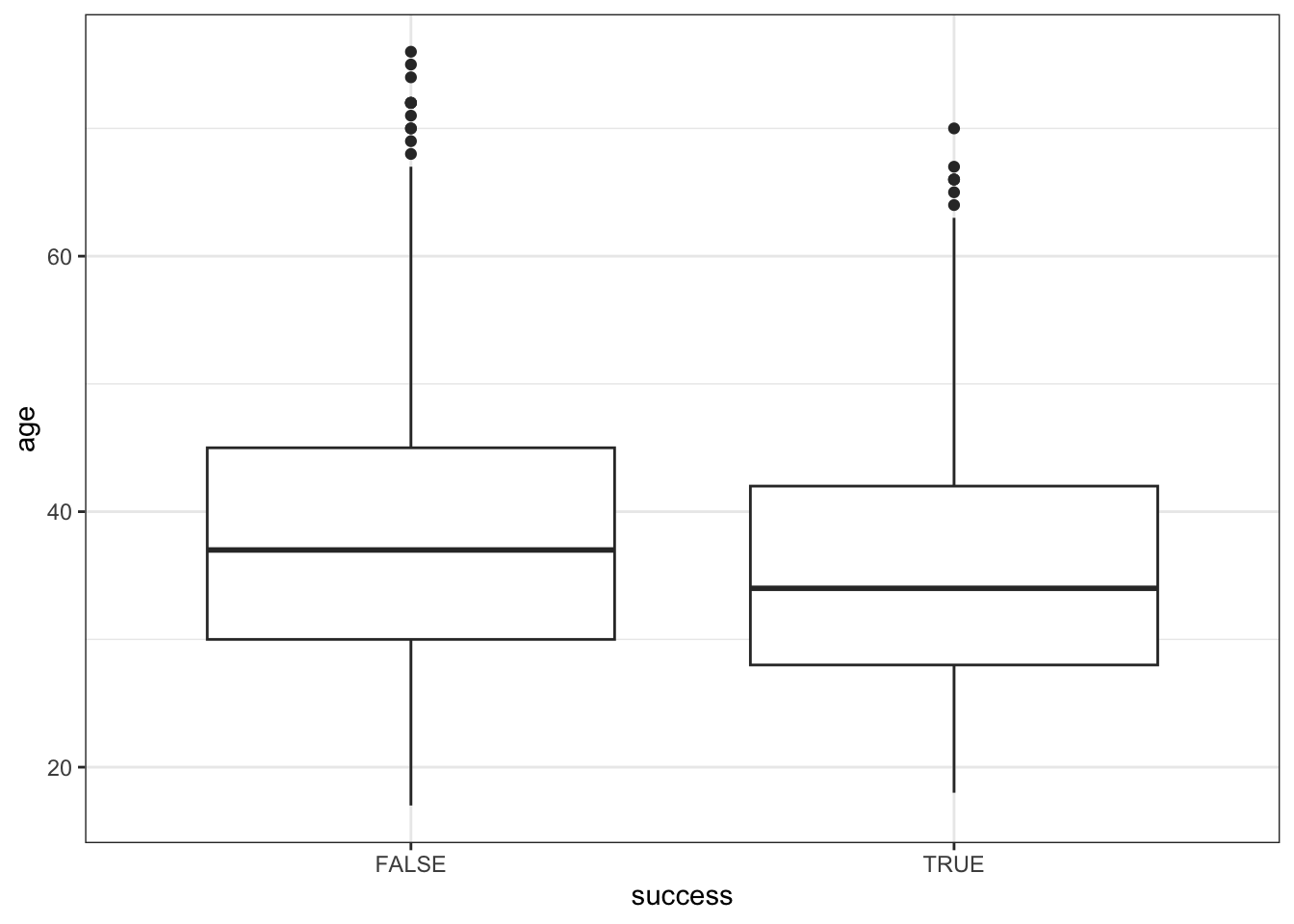

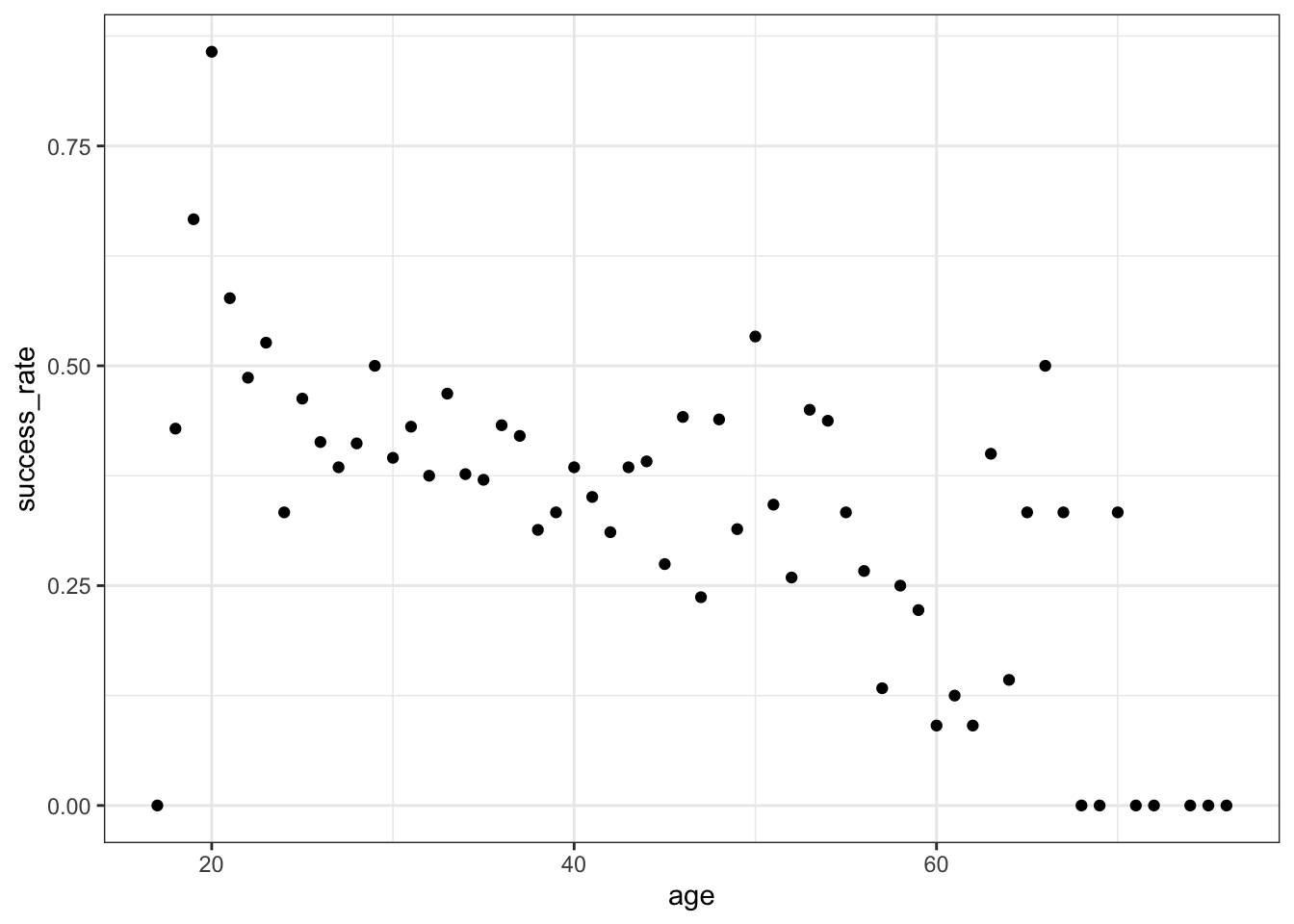

Exercise 2: Visualizing success vs age

Let’s now explore the relationship of success with age. Since success (Y) is categorical and age (X) is quantitative, it can be tempting to draw something like a side-by-side boxplot:

climbers %>%

ggplot(aes(y = age, x = success)) +

geom_boxplot()

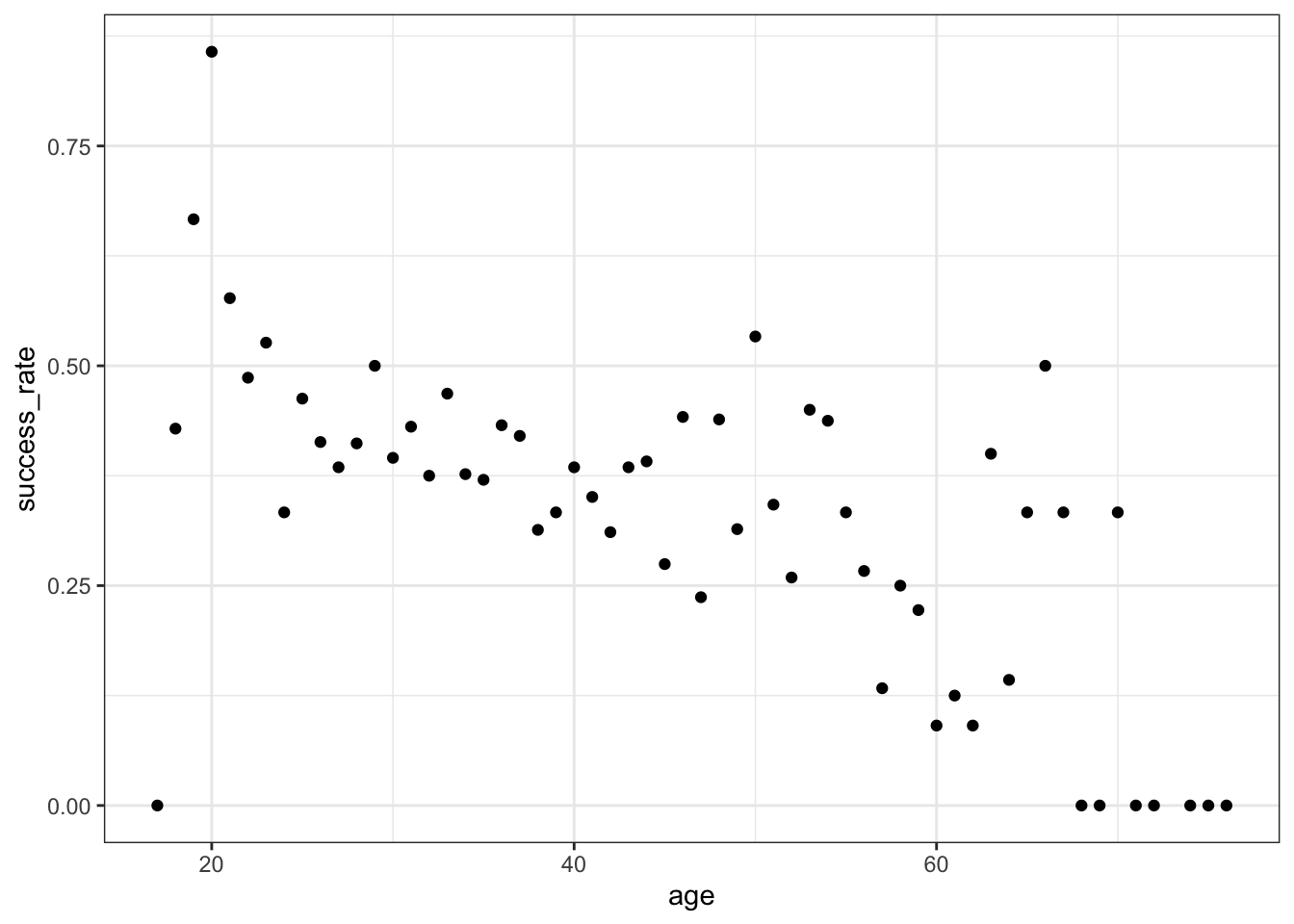

BUT this only gives us insight into the dependence of age on success, not success on age (it reverses the roles of Y and X). Instead, we want to calculate the observed success rate (probability of success) at each age, or in each age bracket.

Part a

Below is a summary of successes and failures at different ages. Calculate the observed success rate (probability of success) for…

18 year olds: ____ / (3 + 4) =

17-19 year olds: ___ / (1 + 4 + 3 + 4 + 8) =

climbers %>%

count(age, success) %>%

head(5)

## # A tibble: 5 × 3

## age success n

## <dbl> <lgl> <int>

## 1 17 FALSE 1

## 2 18 FALSE 4

## 3 18 TRUE 3

## 4 19 FALSE 4

## 5 19 TRUE 8Part b

We can calculate these success rates using group_by() and summarize(). Check that these are consistent with your answers to Part a:

# Calculate success rate by age

climbers %>%

group_by(age) %>%

summarize(success_rate = mean(success)) %>%

head(3)

## # A tibble: 3 × 2

## age success_rate

## <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 17 0

## 2 18 0.429

## 3 19 0.667

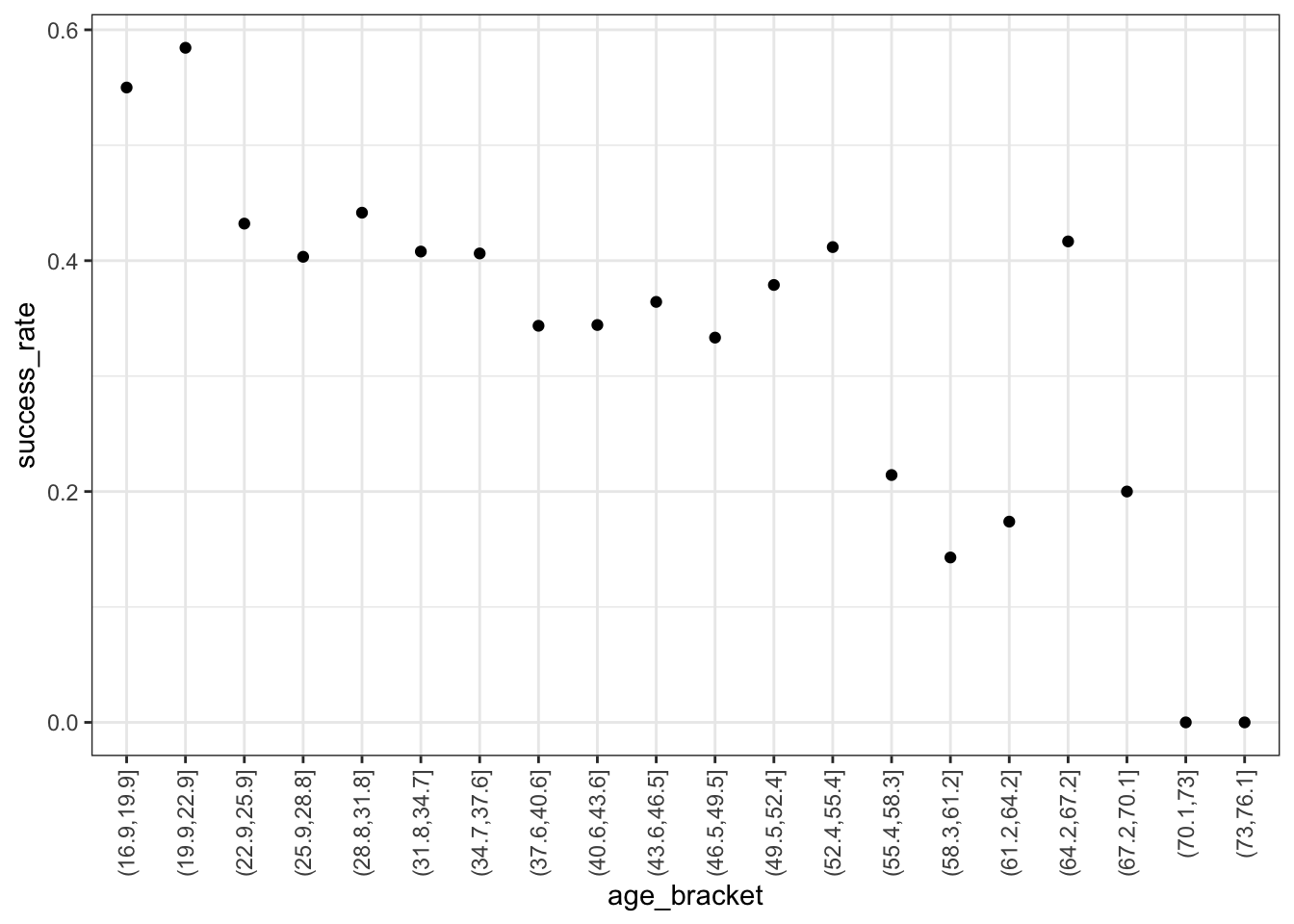

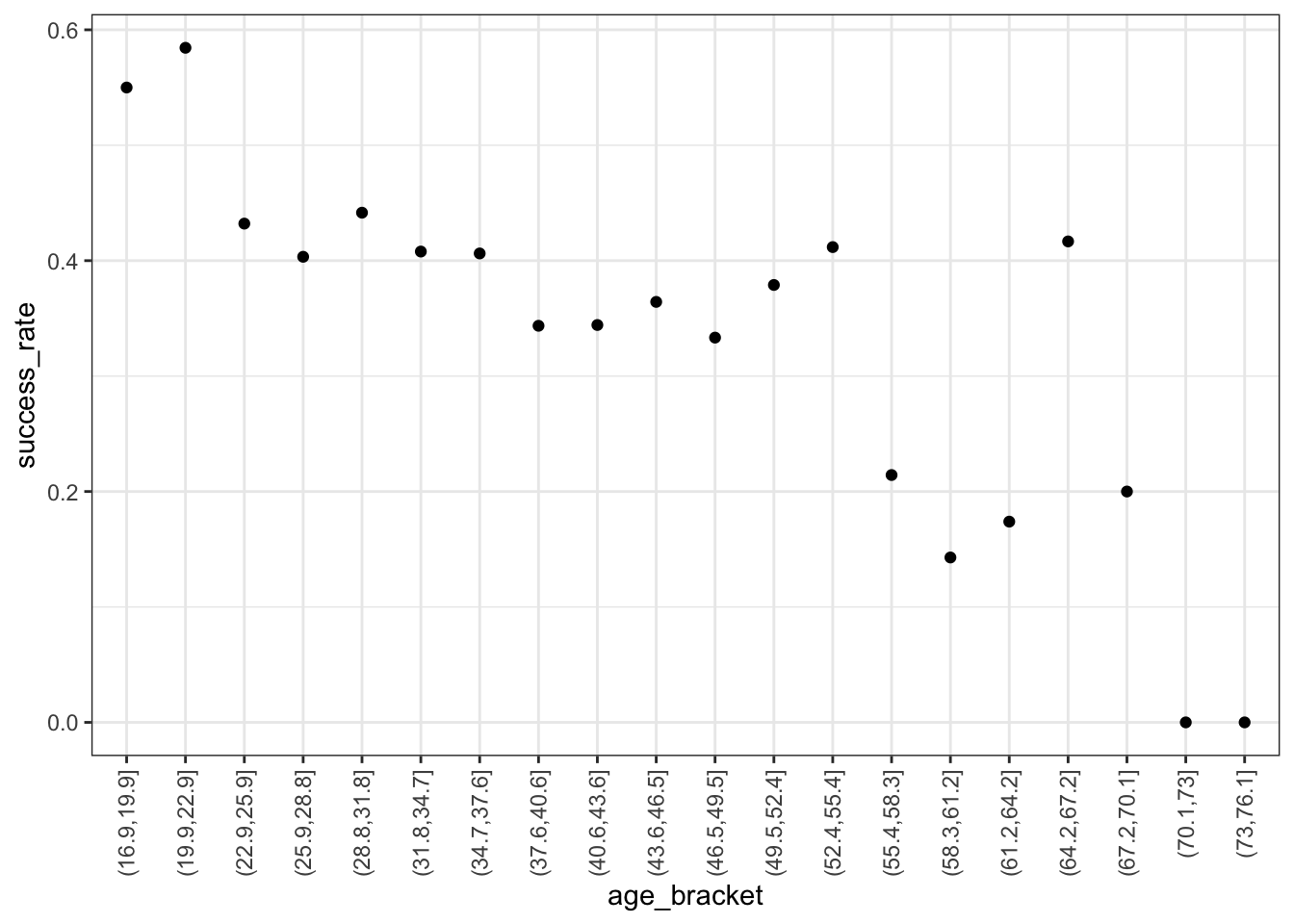

# Split climbers into larger, more stable age brackets

# (This is good when we don't have many observations at each x!)

# Calculate success rate by age bracket

climbers %>%

mutate(age_bracket = cut(age, breaks = 20)) %>%

group_by(age_bracket) %>%

summarize(success_rate = mean(success)) %>%

head(3)

## # A tibble: 3 × 2

## age_bracket success_rate

## <fct> <dbl>

## 1 (16.9,19.9] 0.55

## 2 (19.9,22.9] 0.584

## 3 (22.9,25.9] 0.432Now, plot the success rates by age and age bracket below. Summarize what you learn about the relationship (note that we weren’t able to observe this information from the boxplots!).

climbers %>%

group_by(age) %>%

summarize(success_rate = mean(success)) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = age, y = success_rate)) +

geom_point()

climbers %>%

mutate(age_bracket = cut(age, breaks = 20)) %>%

group_by(age_bracket) %>%

summarize(success_rate = mean(success)) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = age_bracket, y = success_rate)) +

geom_point() +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 90, vjust = 0.5, hjust=1))

Exercise 3: Logistic regression in R

To model the relationship between success and age, we can construct the logistic regression model using the code below. Point out the 2 new things about this code.

climbing_model_1 <- glm(success ~ age, data = climbers, family = "binomial")

coef(summary(climbing_model_1))

## Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

## (Intercept) 0.42568563 0.169177382 2.516209 1.186249e-02

## age -0.02397199 0.004489504 -5.339564 9.317048e-08

Exercise 4: Writing out & plotting the model

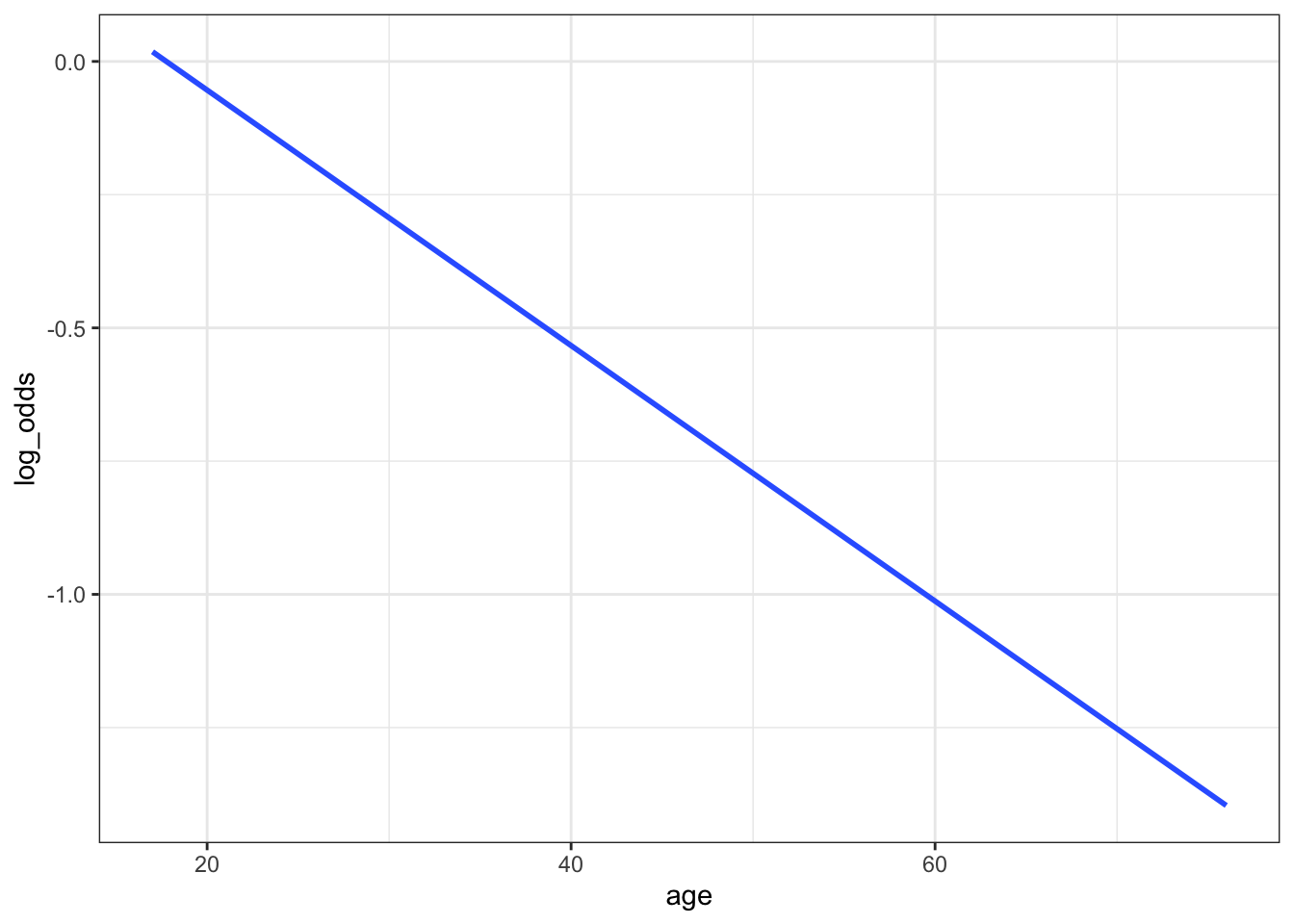

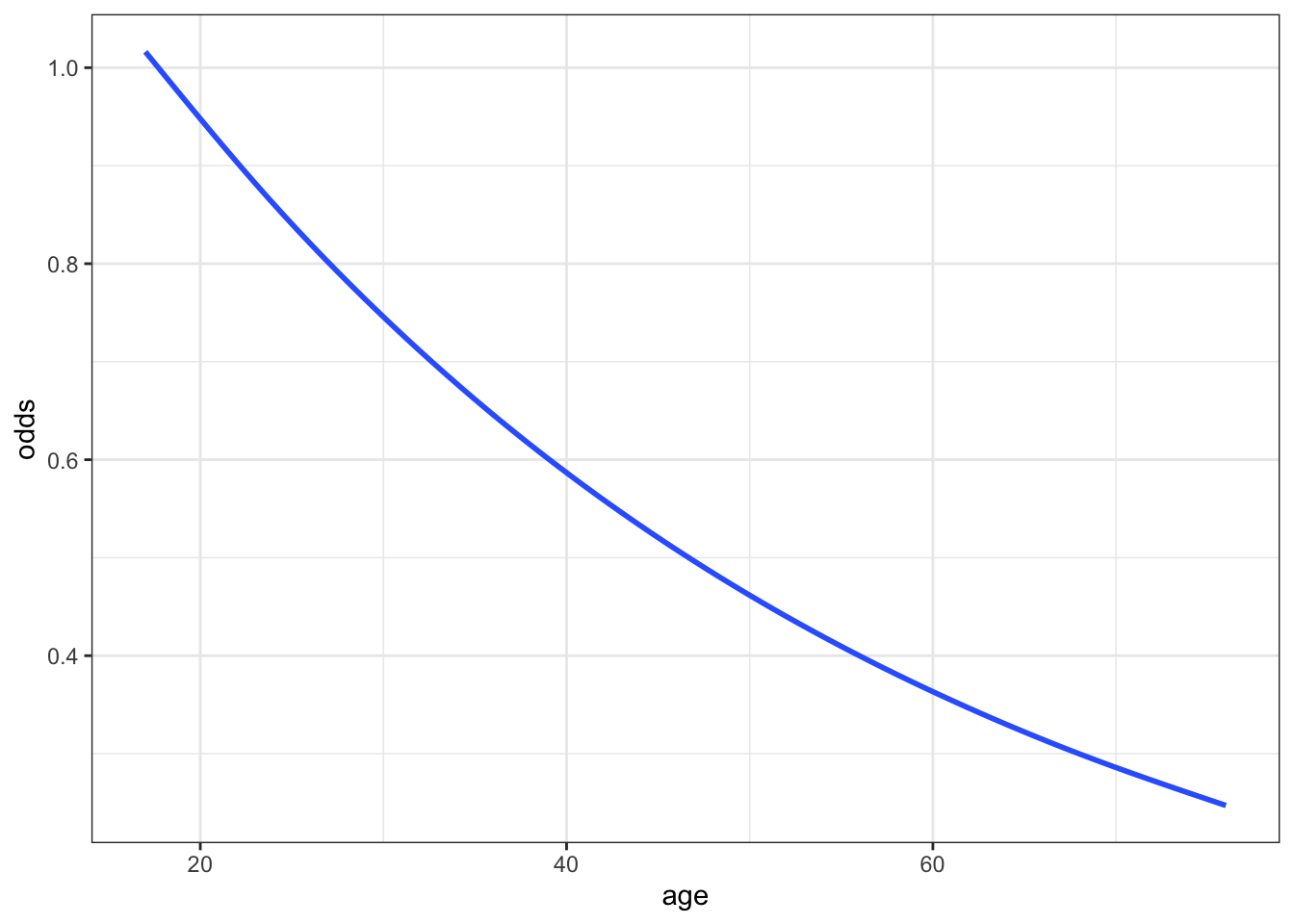

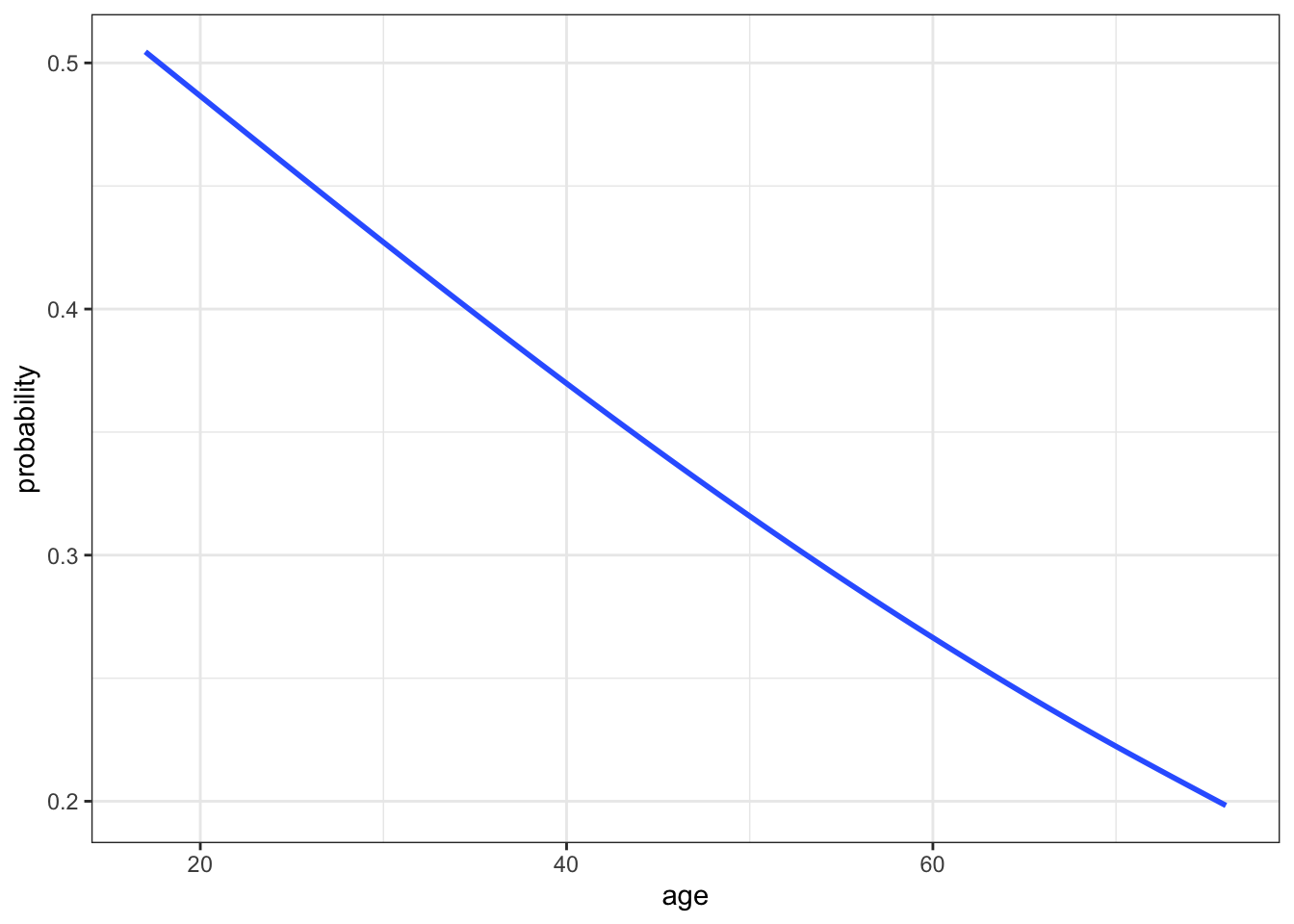

The estimated model formula is stated below on the log(odds), odds, and probability scales.

log(odds of success) = 0.42569 - 0.02397age

odds of success = \(e^{0.42569 - 0.02397\text{age}}\)

probability of success = \(e^{0.42569 - 0.02397\text{age}}\) / (\(e^{0.42569 - 0.02397\text{age}}\) + 1)

Part a

Convince yourselves that you know where the above formulas come from!

Part b

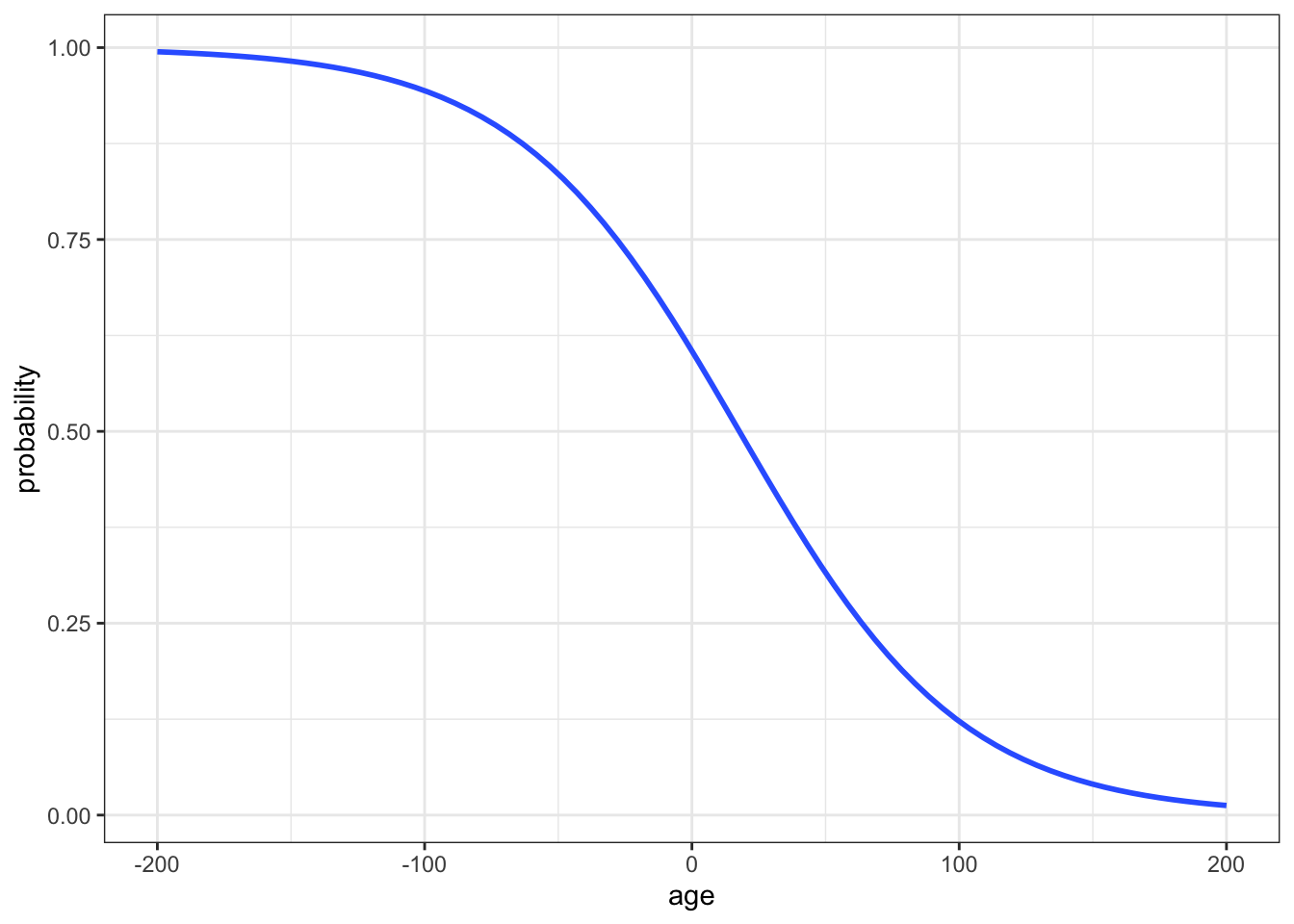

Our one model, expressed on different scales, is plotted below. As with the plot of our data on success rates in Exercise 3, these indicate that success rate decreases with age. (This is true on every scale, of course.) Compare the shapes of the models on these different scales.

- Which model is linear?

- Which model is S-shaped?

- Which model is restricted between 0 and 1 on the y-axis?

- Which model is curved and restricted to be above 0 (but not necessarily below 1) on the y-axis?

# Incorporate predictions on the probability, odds, & log-odds scales

climbers_predictions <- climbers %>%

mutate(probability = climbing_model_1$fitted.values) %>%

mutate(odds = probability / (1-probability)) %>%

mutate(log_odds = log(odds))

# Plot the model on the log-odds scale

ggplot(climbers_predictions, aes(x = age, y = log_odds)) +

geom_smooth(se = FALSE)

# Plot the model on the odds scale

ggplot(climbers_predictions, aes(x = age, y = odds)) +

geom_smooth(se = FALSE)

# Plot the model on the probability scale

ggplot(climbers_predictions, aes(x = age, y = probability)) +

geom_smooth(se = FALSE)

#...and zoom out to see broader (and impossible) age range

ggplot(climbers_predictions, aes(x = age, y = as.numeric(success))) +

geom_smooth(method = "glm", method.args = list(family = "binomial"), se = FALSE, fullrange = TRUE) +

labs(y = "probability") +

lims(x = c(-200,200))

Exercise 5: Predictions

Let’s use the model formulas from the above exercise to make predictions. Consider a 20-year-old climber.

Part a

Calculate the log(odds) that this climber will succeed. HINT: use the log(odds) model.

Part b

Calculate the odds that this climber will succeed. HINT: Either transform the log(odds) prediction or use the odds model.

Part c

Calculate the probability that this climber will succeed. HINT: Either transform the odds prediction or use the probability model.

Part d

Check your calculations 2 ways:

- Are they consistent with the model visualizations above?

- Do they match the results of the

predict()function?

# Check the log-odds prediction

predict(climbing_model_1, newdata = data.frame(age = 20))

## 1

## -0.05375421

# Check the odds prediction

exp(predict(climbing_model_1, newdata = data.frame(age = 20)))

## 1

## 0.947665

# Check the probability prediction

predict(climbing_model_1, newdata = data.frame(age = 20), type = "response")

## 1

## 0.4865647

Exercise 6: Interpreting the intercept

In using the logistic regression model, it’s important to interpret the coefficients. Let’s learn how to do that, starting with the intercept of our model: log(odds of success) = 0.42569 - 0.02397age. Since the model on the log(odds) scale is just a line, we can interpret the intercept as usual:

Among 0 year old climbers (lol), the log(odds of success) is 0.42569.

But who cares?! It’s tough to interpret log(odds). Translate that statement to the odds scale:

Among 0 year old climbers (lol), the odds of success are…

Exercise 7: Interpreting the age coefficient

Since the model on the log(odds) scale is just a line, we can also interpret the age coefficient as the slope of that line:

A 1-year increase in age is associated with a decrease of 0.02397 in the log(odds of success), on average.

Again, since that’s hard to understand, we can convert the age coefficient to the odds scale: \(e^{-0.02397} = 0.976313\). BUT since the odds model is NOT linear, we can’t interpret this as a slope. So what does it mean?

Part a

Below are the odds of success among various ages:

exp(predict(climbing_model_1, newdata = data.frame(age = 23)))

## 1

## 0.8819057

exp(predict(climbing_model_1, newdata = data.frame(age = 22)))

## 1

## 0.9033021

exp(predict(climbing_model_1, newdata = data.frame(age = 21)))

## 1

## 0.9252177

exp(predict(climbing_model_1, newdata = data.frame(age = 20)))

## 1

## 0.947665Calculate and interpret the odds ratio of success, comparing 23-year-olds to 22-year-olds. (Do not use rounded numbers in this calculation or those below!)

Part b

Calculate and interpret the odds ratio of success, comparing 22-year-olds to 21-year-olds.

Part c

Calculate and interpret the odds ratio of success, comparing 21-year-olds to 20-year-olds.

Part d

Summarize the punchline here.

On the log(odds) scale, the

agecoefficient is 0.02397:

On average, for every 1-year increase in age, log(odds of success) decrease by 0.02397.On the odds scale, the

agecoefficient is \(e^{-0.02397} = 0.976313\):

On average, for every 1-year increase in age, odds of success are ???% as high.That is, they decrease by ???%

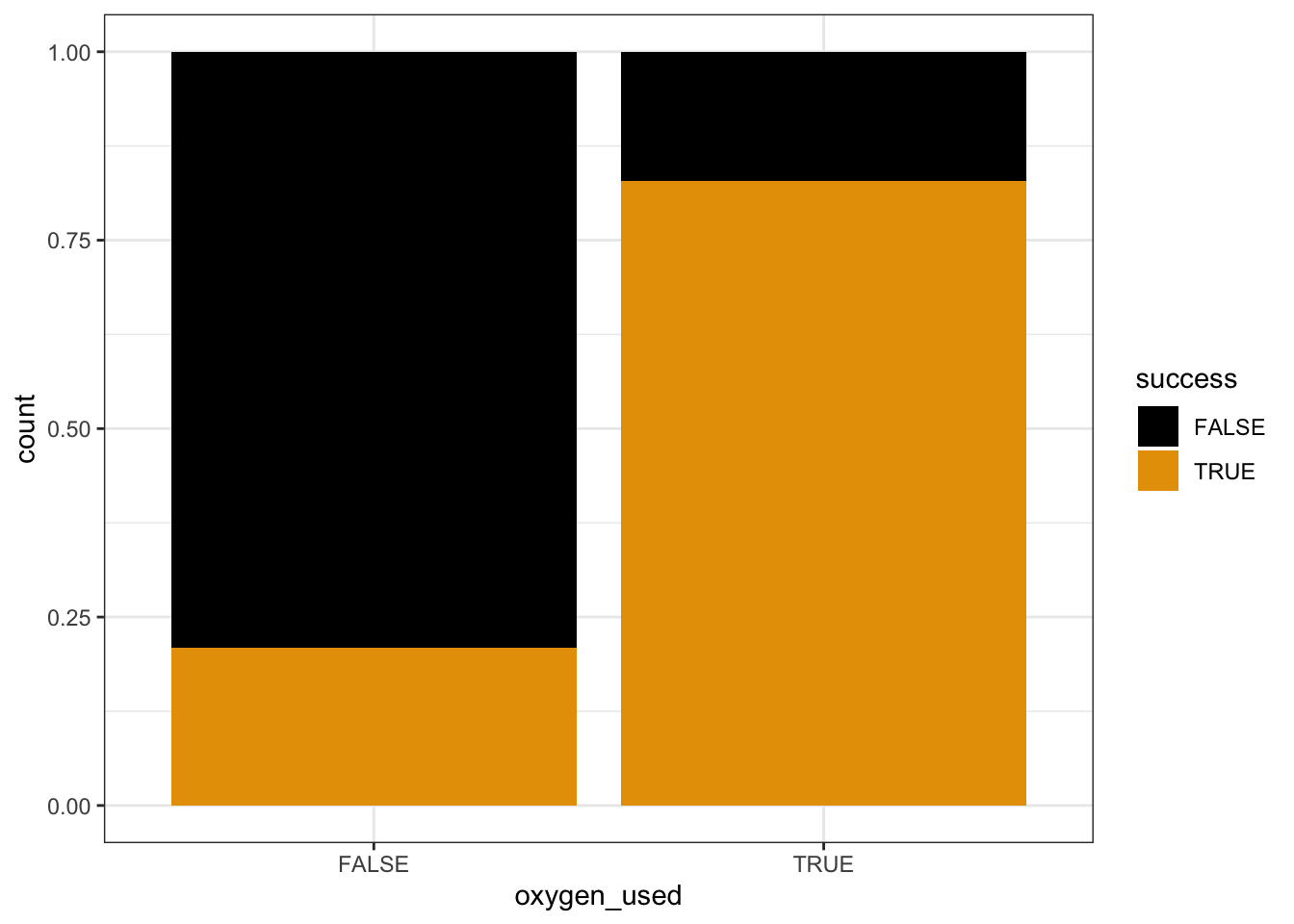

Exercise 8: Another climbing model

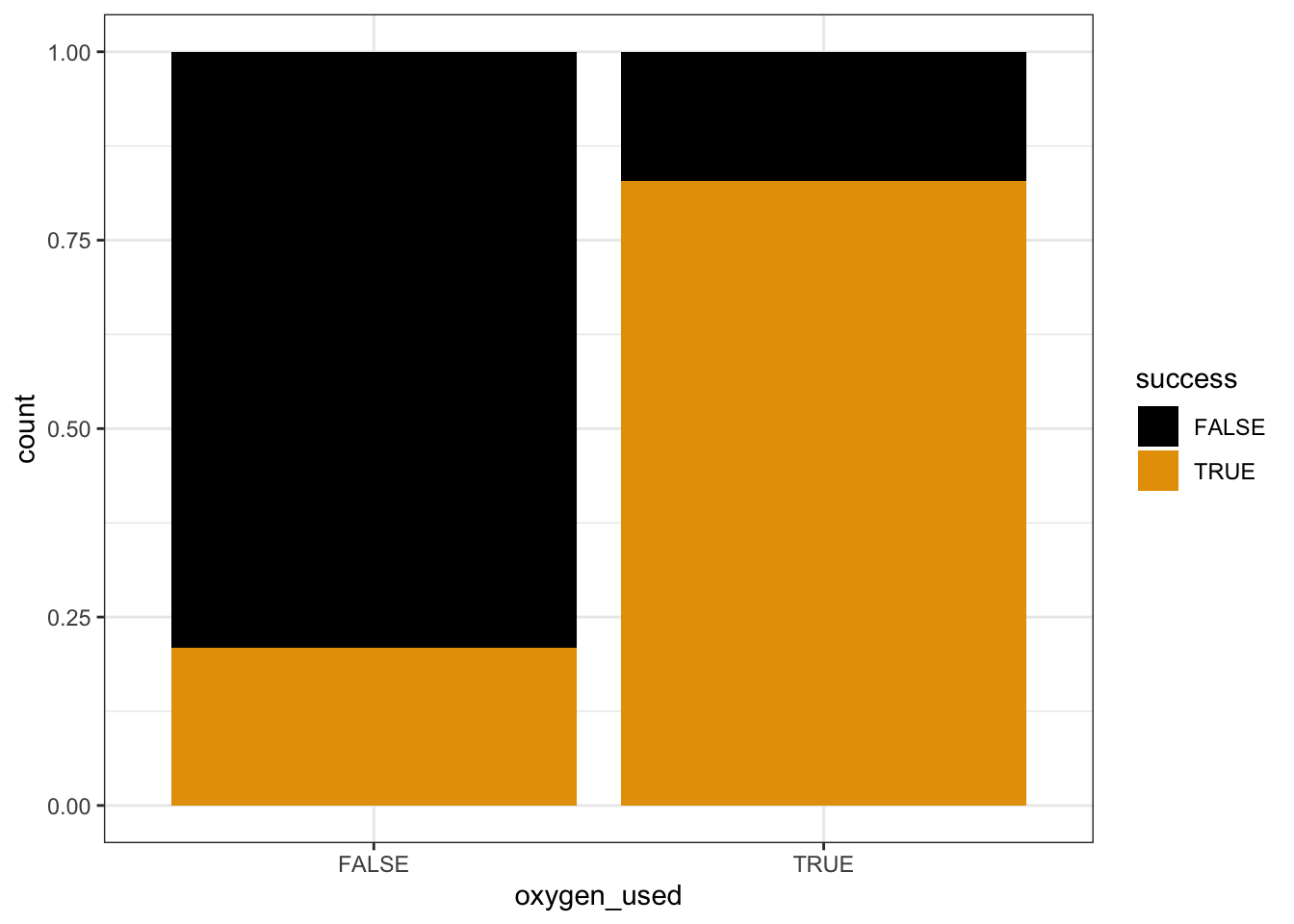

Next, let’s explore the relationship of success (Y) with oxygen_used (X). Since both variables are categorical, we can fill in a bar plot of X with the categories of Y:

# Plot the relationship

climbers %>%

ggplot(aes(x = oxygen_used, fill = success)) +

geom_bar(position = "fill")

# Model the relationship

climbing_model_2 <- glm(success ~ oxygen_used, data = climbers, family = "binomial")

coef(summary(climbing_model_2))

## Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

## (Intercept) -1.327993 0.0639834 -20.75528 1.098514e-95

## oxygen_usedTRUE 2.903864 0.1257404 23.09412 5.304291e-118Thus the estimated model formula is:

log(odds of success) = -1.327993 + 2.903864 oxygen_usedTRUE

Part a

Describe what you learn about the relationship from the plot alone.

Part b

Calculate:

- the odds of success for a climber that doesn’t use oxygen

- the probability of success for a climber that doesn’t use oxygen

Part c

Calculate:

- the odds of success for a climber that uses oxygen

- the probability of success for a climber that uses oxygen

Part d

Check that your probability and odds calculations match those below:

exp(predict(climbing_model_2, newdata = data.frame(oxygen_used = FALSE)))

## 1

## 0.2650086

predict(climbing_model_2, newdata = data.frame(oxygen_used = FALSE), type = "response")

## 1

## 0.2094915

exp(predict(climbing_model_2, newdata = data.frame(oxygen_used = TRUE)))

## 1

## 4.834951

predict(climbing_model_2, newdata = data.frame(oxygen_used = TRUE), type = "response")

## 1

## 0.828619Part e

Calculate and interpret the odds ratio of success, comparing climbers that do use oxygen to those that don’t. NOTE: Your calculation should be above 1!!

Exercise 9: Interpreting coefficients

Let’s interpret the coefficients of our logistic regression model:

log(odds of success) = -1.327993 + 2.903864 oxygen_usedTRUE

On the log(odds) scale:

- The log(odds of success) for climbers that don’t use oxygen is -1.327993.

- The log(odds of success) is 2.903864 higher for climbers that use oxygen than for those that don’t.

Yuk. Convert those coefficients to the odds scale:

exp(-1.327993)

exp(2.903864)Part a

How can we interpret the intercept on the odds scale, 0.265? Where have you observed this number before?!

Part b

How can we interpret the oxygen_usedTRUE coefficient on the odds scale, 18.24? Where have you observed this number before?!

Exercise 10: Connecting tables to logistic regression

For the simple logistic regression model with 1 predictor, which is categorical, the model coefficients can be calculated from the table of counts! Here rows represent whether oxygen was used and columns represent whether the climber was successful:

# Rows correspond to oxygen_used

# Columns correspond to success

climbers %>%

tabyl(oxygen_used, success) %>%

adorn_totals(c("row", "col"))

## oxygen_used FALSE TRUE Total

## FALSE 1166 309 1475

## TRUE 103 498 601

## Total 1269 807 2076Part a

Use this table to calculate the odds of success for somebody that didn’t use oxygen. Where have you observed this number before?! HINT: Use the FALSE row.

Part b

Use this table to calculate the odds ratio of success, comparing climbers that do use oxygen to those that don’t. Where have you observed this number before?! HINT: You’ll first need to calculate the odds of success for people that use oxygen.

Exercise 11: Interpreting logistic regression coefficients

In general (not just for climbers), let’s summarize how to interpret logistic regression coefficients. Review the details below and convince yourself that these general properties are consistent with your work above. Let \(Y\) be a binary categorical response variable (eg: Y = 1 if the event of interest happens and is 0 otherwise). Then a logistic regression model of \(Y\) by \(Y\) is

\[\log(\text{odds}) = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X\]

- Coefficient interpretation for quantitative X

\[\begin{split} \beta_0 & = \text{ LOG(ODDS) when } X=0 \\ e^{\beta_0} & = \text{ ODDS when } X=0 \\ \beta_1 & = \text{ change in LOG(ODDS) per 1 unit increase in } X \\ e^{\beta_1} & = \text{ multiplicative change in ODDS per 1 unit increase in } X \text{ (ie. the odds ratio, comparing the odds for X + 1 vs X)} \\ \end{split}\] - Coefficient interpretation for categorical X

\[\begin{split} \beta_0 & = \text{ LOG(ODDS) at the reference category } \\ e^{\beta_0} & = \text{ ODDS at the reference category } \\ \beta_1 & = \text{ unit change in LOG(ODDS) relative to the reference} \\ e^{\beta_1} & = \text{ multiplicative change in ODDS relative to the reference } \text{ (ie. the odds ratio, comparing the odds for the given category vs the reference category)} \\ \end{split}\]

Exercise 12: R code

A lot of R code was used to produce the plots and other output above. The code is not the point. It’s more important to understand the logistic regression concepts, and the output of the code – you can always look up code. With that in mind, review the code to get a sense for the structure!

Exercise 13: VERY optional math challenge

Consider a simple logistic regression model:

\[\log(\text{odds}) = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X\]

Prove that \(e^{\beta_1}\) indicates the MULTIPLICATIVE change in ODDS for a 1-unit increase in X, i.e. that it’s equivalent to the odds ratio for “X+1” vs “X”.

Solutions

EXAMPLE 1: Normal or logistic?

- Normal. Y is quantitative.

- Normal. Y is quantitative.

- Logistic. Y is binary.

EXAMPLE 2: probability vs odds vs log(odds)

# a.

# odds

0.9 / (1 - 0.9)

# log(odds)

log(9)

# b.

# odds

exp(-1.0986)

# prob

0.333 / (0.333 + 1)

EXAMPLE 3: Conditional odds

library(tidyverse)

titanic <- read_csv("https://mac-stat.github.io/data/titanic.csv")

head(titanic)

## # A tibble: 6 × 5

## Name PClass Age Sex Survived

## <chr> <chr> <dbl> <chr> <dbl>

## 1 Allen, Miss Elisabeth Walton 1st 29 female 1

## 2 Allison, Miss Helen Loraine 1st 2 female 0

## 3 Allison, Mr Hudson Joshua Creighton 1st 30 male 0

## 4 Allison, Mrs Hudson JC (Bessie Waldo Daniels) 1st 25 female 0

## 5 Allison, Master Hudson Trevor 1st 0.92 male 1

## 6 Anderson, Mr Harry 1st 47 male 1

titanic %>%

count(PClass, Survived)

## # A tibble: 7 × 3

## PClass Survived n

## <chr> <dbl> <int>

## 1 1st 0 129

## 2 1st 1 193

## 3 2nd 0 160

## 4 2nd 1 119

## 5 3rd 0 573

## 6 3rd 1 138

## 7 <NA> 0 1

library(janitor)

titanic %>%

tabyl(PClass, Survived, show_na = FALSE) %>%

adorn_totals(c("row", "col"))

## PClass 0 1 Total

## 1st 129 193 322

## 2nd 160 119 279

## 3rd 573 138 711

## Total 862 450 1312.

# probability of survival 450 / 1312 # odds of survival (450 / 1312) / (1 - (450 / 1312))Survival was most likely for 1st class passengers and least likely for 3rd class passengers. NOTE: The first plot makes more clear that there were more 3rd class passengers, but the second plot makes it easier to compare survival rates among each class.

titanic %>%

ggplot(aes(x = PClass, fill = factor(Survived))) +

geom_bar()

titanic %>%

ggplot(aes(x = PClass, fill = factor(Survived))) +

geom_bar(position = "fill")

.

# probability of survival for 1st class 193 / 322 ## [1] 0.5993789 # odds of survival for 1st class (193 / 322) / (1 - (193 / 322)) ## [1] 1.496124.

# probability of survival for 3rd class 138 / 711 ## [1] 0.1940928 # odds of survival for 3rd class (138 / 711) / (1 - (138 / 711)) ## [1] 0.2408377

EXAMPLE 4: Odds ratios

The odds of survival were more than 6 times higher for 1st class vs 3rd class:

# odds of survival for 1st class / odds of survival for 3rd class 1.50 / 0.24The odds of survival for 3rd class passengers were only 16% as high as those for 1st class passengers (i.e. they were 84% lower):

# odds of survival for 3rd class / odds of survival for 1st class 0.24 / 1.50

# Load packages and data

library(tidyverse)

climbers <- read_csv("https://mac-stat.github.io/data/climbers_sub.csv") %>%

select(peak_name, success, age, oxygen_used, height_metres)

# Check out the first 6 rows

head(climbers)

## # A tibble: 6 × 5

## peak_name success age oxygen_used height_metres

## <chr> <lgl> <dbl> <lgl> <dbl>

## 1 Ama Dablam TRUE 28 FALSE 6814

## 2 Ama Dablam TRUE 27 FALSE 6814

## 3 Ama Dablam TRUE 35 FALSE 6814

## 4 Ama Dablam TRUE 37 FALSE 6814

## 5 Ama Dablam TRUE 43 FALSE 6814

## 6 Ama Dablam FALSE 38 FALSE 6814Exercise 1: Getting to know Y

Roughly 40% of climbers succeed.

climbers %>%

count(success)

## # A tibble: 2 × 2

## success n

## <lgl> <int>

## 1 FALSE 1269

## 2 TRUE 807

climbers %>%

ggplot(aes(x = success)) +

geom_bar()

Exercise 2: Visualizing success vs age

Part a

climbers %>%

count(age, success) %>%

head(5)

## # A tibble: 5 × 3

## age success n

## <dbl> <lgl> <int>

## 1 17 FALSE 1

## 2 18 FALSE 4

## 3 18 TRUE 3

## 4 19 FALSE 4

## 5 19 TRUE 818 year olds: 3 / (3 + 4) = 0.43

17-19 year olds: (3 + 8) / (1 + 4 + 3 + 4 + 8) = 0.55

Part b

Success rates start at nearly 60% for teenagers, then decrease with age – success rates approach 0 for climbers in their 70s.

# Calculate success rate by age

climbers %>%

group_by(age) %>%

summarize(success_rate = mean(success))

## # A tibble: 59 × 2

## age success_rate

## <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 17 0

## 2 18 0.429

## 3 19 0.667

## 4 20 0.857

## 5 21 0.577

## 6 22 0.486

## 7 23 0.526

## 8 24 0.333

## 9 25 0.463

## 10 26 0.413

## # ℹ 49 more rows

# Split climbers into larger, more stable age brackets

# (This is good when we don't have many observations at each x!)

# Calculate success rate by age bracket

climbers %>%

mutate(age_bracket = cut(age, breaks = 20)) %>%

group_by(age_bracket)

## # A tibble: 2,076 × 6

## # Groups: age_bracket [20]

## peak_name success age oxygen_used height_metres age_bracket

## <chr> <lgl> <dbl> <lgl> <dbl> <fct>

## 1 Ama Dablam TRUE 28 FALSE 6814 (25.9,28.8]

## 2 Ama Dablam TRUE 27 FALSE 6814 (25.9,28.8]

## 3 Ama Dablam TRUE 35 FALSE 6814 (34.7,37.6]

## 4 Ama Dablam TRUE 37 FALSE 6814 (34.7,37.6]

## 5 Ama Dablam TRUE 43 FALSE 6814 (40.6,43.6]

## 6 Ama Dablam FALSE 38 FALSE 6814 (37.6,40.6]

## 7 Ama Dablam TRUE 23 FALSE 6814 (22.9,25.9]

## 8 Ama Dablam FALSE 36 FALSE 6814 (34.7,37.6]

## 9 Ama Dablam TRUE 48 FALSE 6814 (46.5,49.5]

## 10 Ama Dablam TRUE 25 FALSE 6814 (22.9,25.9]

## # ℹ 2,066 more rows

climbers %>%

group_by(age) %>%

summarize(success_rate = mean(success)) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = age, y = success_rate)) +

geom_point()

climbers %>%

mutate(age_bracket = cut(age, breaks = 20)) %>%

group_by(age_bracket) %>%

summarize(success_rate = mean(success)) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = age_bracket, y = success_rate)) +

geom_point() +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 90, vjust = 0.5, hjust=1))

Exercise 3: Logistic regression in R

We’re using glm instead of lm, and add family = "binomial" to specify that this is a logistic model:

climbing_model_1 <- glm(success ~ age, data = climbers, family = "binomial")

coef(summary(climbing_model_1))

## Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

## (Intercept) 0.42568563 0.169177382 2.516209 1.186249e-02

## age -0.02397199 0.004489504 -5.339564 9.317048e-08

Exercise 4: Writing out & plotting the model

- .

- log(odds) model

- probability model

- probability model

- odds model

- log(odds) model

Exercise 5: Predictions

#a

log_odds <- 0.42568563 - 0.02397199 * 20

log_odds

## [1] -0.05375417

#b

odds <- exp(log_odds)

odds

## [1] 0.947665

#c

prob <- odds / (odds + 1)

prob

## [1] 0.4865647

#d

predict(climbing_model_1, newdata = data.frame(age = 20))

## 1

## -0.05375421

exp(predict(climbing_model_1, newdata = data.frame(age = 20)))

## 1

## 0.947665

predict(climbing_model_1, newdata = data.frame(age = 20), type = "response")

## 1

## 0.4865647

Exercise 6: Interpreting the intercept

Among 0 year old climbers (lol), the odds of success is 1.5, i.e. 1.5 times more likely than not.

exp(0.42569)

Exercise 7: Interpreting the age coefficient

exp(predict(climbing_model_1, newdata = data.frame(age = 23)))

## 1

## 0.8819057

exp(predict(climbing_model_1, newdata = data.frame(age = 22)))

## 1

## 0.9033021

exp(predict(climbing_model_1, newdata = data.frame(age = 21)))

## 1

## 0.9252177

exp(predict(climbing_model_1, newdata = data.frame(age = 20)))

## 1

## 0.947665Part a

The odds of success for a 23-year-old are 97.6% as high as those for a 22-year-old (i.e. the odds are 2.4% lower).

0.8819057 / 0.9033021Part b

The odds of success for a 22-year-old are 97.6% as high as those for a 21-year-old (i.e. the odds are 2.4% lower).

0.9033021 / 0.9252177Part c

The odds of success for a 21-year-old are 97.6% as high as those for a 20-year-old (i.e. the odds are 2.4% lower).

0.9252177 / 0.947665Part d

On the log(odds) scale, the

agecoefficient is 0.02397:

On average, for every 1-year increase in age, log(odds of success) decrease by 0.02397.On the odds scale, the

agecoefficient is \(e^{-0.02397} = 0.976313\):

On average, for every 1-year increase in age, odds of success are 97.6% as high. That is, they decrease by 2.4%.

Exercise 8: Another climbing model

# Plot the relationship

climbers %>%

ggplot(aes(x = oxygen_used, fill = success)) +

geom_bar(position = "fill")

# Model the relationship

climbing_model_2 <- glm(success ~ oxygen_used, data = climbers, family = "binomial")

coef(summary(climbing_model_2))

## Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

## (Intercept) -1.327993 0.0639834 -20.75528 1.098514e-95

## oxygen_usedTRUE 2.903864 0.1257404 23.09412 5.304291e-118Part a

Success is more likely if you use oxygen. The probability of success appears to be between 85% and 90% for people that use oxygen, and under 25% for people that don’t.

Part b

# log(odds)

-1.327993

# odds

exp(-1.327993)

# probability

exp(-1.327993) / (exp(-1.327993) + 1)Part c

# log(odds)

-1.327993 + 2.903864

# odds

exp(-1.327993 + 2.903864)

# probability

exp(-1.327993 + 2.903864) / (exp(-1.327993 + 2.903864) + 1)Part d

exp(predict(climbing_model_2, newdata = data.frame(oxygen_used = FALSE)))

## 1

## 0.2650086

predict(climbing_model_2, newdata = data.frame(oxygen_used = FALSE), type = "response")

## 1

## 0.2094915

exp(predict(climbing_model_2, newdata = data.frame(oxygen_used = TRUE)))

## 1

## 4.834951

predict(climbing_model_2, newdata = data.frame(oxygen_used = TRUE), type = "response")

## 1

## 0.828619Part e

4.834951 / 0.2650086

## [1] 18.24451

Exercise 9: Interpreting coefficients

Part a

This is the odds of success for somebody that doesn’t use oxygen (the reference level).

Part b

This is the odds ratio of success, comparing climbers that use oxygen to those that don’t. The odds of success are 18 times higher if using oxygen.

Exercise 10: Connecting tables to logistic regression

# Rows correspond to oxygen_used

# Columns correspond to success

climbers %>%

tabyl(oxygen_used, success) %>%

adorn_totals(c("row", "col"))

## oxygen_used FALSE TRUE Total

## FALSE 1166 309 1475

## TRUE 103 498 601

## Total 1269 807 2076Part a

This is the intercept coefficient on the odds scale!

# probability of success (no oxygen)

309 / 1475

## [1] 0.2094915

# odds of success (no oxygen)

(309 / 1475) / (1 - (309 / 1475))

## [1] 0.2650086Part b

This is the oxygen_usedTRUE coefficient on the odds scale!

# probability of success (oxygen)

498 / 601

## [1] 0.828619

# odds of success (oxygen)

(498 / 601) / (1 - (498 / 601))

## [1] 4.834951

# odds ratio

4.834951 / 0.2650086

## [1] 18.24451