bikes <- read_csv("https://mac-stat.github.io/data/bikeshare.csv") %>%

rename(rides = riders_casual)

# Build sample models

bike_model_1 <- lm(rides ~ weekend + temp_feel + temp_actual, bikes)

bike_model_2 <- lm(rides ~ temp_feel + temp_actual, bikes)

bike_model_3 <- lm(rides ~ weekend, bikes)21 F-Tests & Nested Models

Announcements etc

SETTLING IN

- This is a paper day! Put away laptops and phones.

- After class, you can access the qmd here: “21-f-tests-notes.qmd”.

WRAPPING UP

Upcoming due dates:

- Thursday: PP 8

- If you plan to use an extension, first check how many of the 3 available extensions you have left. These are tracked at the PP Extensions on Moodle.

- If you’ve used 3 extensions, please remember that per course policy, future late PP / homework will not be accepted for credit. I recommend starting PP 8 early and handing in whatever you have completed by the due date – it’s better to get partial credit than no credit. Happy to chat about other strategies, but the main one is starting early :)

- Tuesday: Project final submission

- Finals week: Quiz 3

- 3:00-4:30pm section: Saturday, 12/13 from 1:30-3:30pm

- 1:20-2:50pm section: Tuesday, 12/16 from 1:30-3:30pm

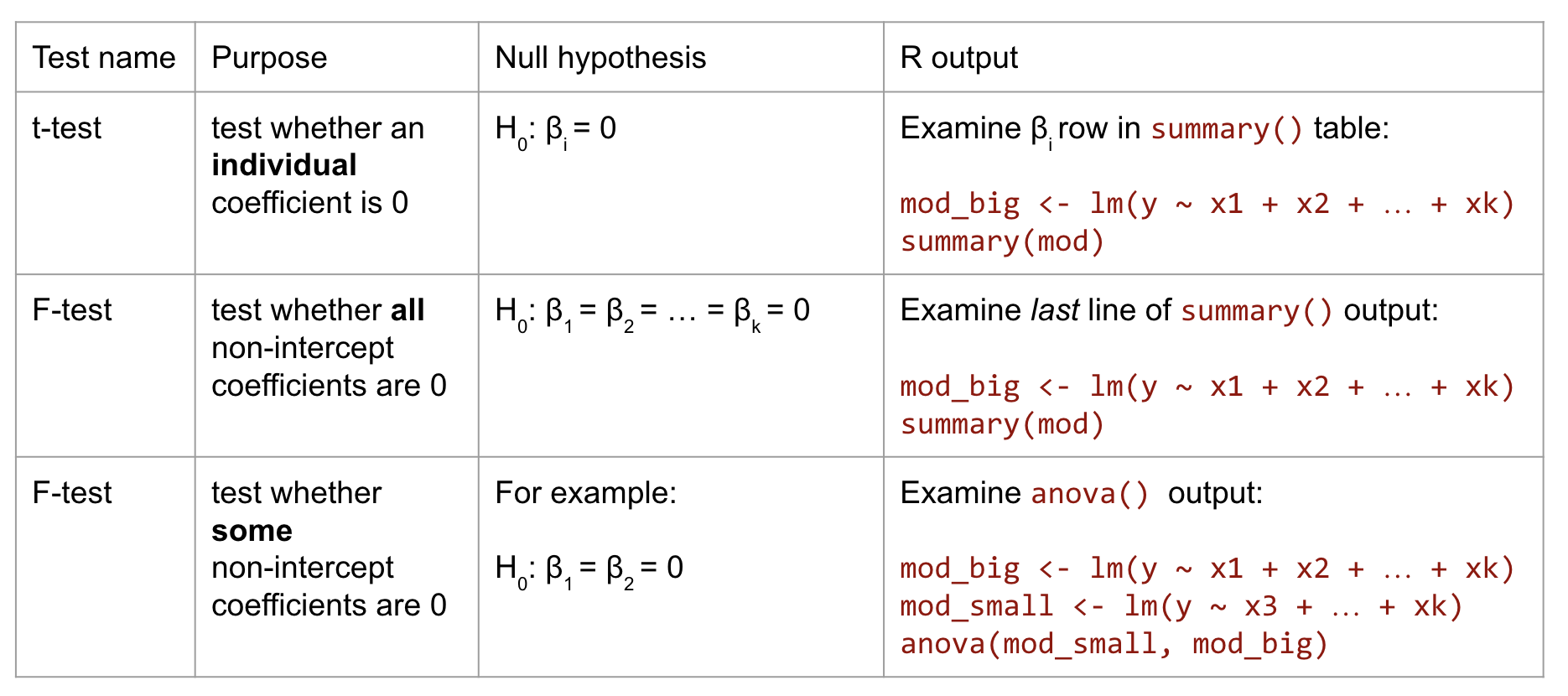

- Determine if one model is nested within another

- Determine which null and alternative hypotheses require an F-test

- Determine which F-tests require the use of the

anovafunction in R vs. the overall F-test given in regular regression output - Interpret the results of an F-test in context

References

The F-test test statistic is not calculated like the t-test test statistic, thus cannot be interpreted the same way! Check out the optional math box below to learn how this statistic is calculated.

Consider 2 models which we’ll estimate using \(n\) data points:

- Model 1 (Big model)

- \(E[Y|X_1,...,X_k,...,X_p] = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X_1 + \cdots + \beta_k X_k + \cdots + \beta_p X_p\)

- “Residual Sum of Squares”: \(RSS_1 = \sum_{i=1}^n (Y_i - \hat{Y}_i)^2\) where \(\hat{Y}_i\) are the predictions calculated from Model 1

- Model 2 (Small model)

- \(E[Y|X_1,...,X_k] = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X_1 + \cdots + \beta_k X_k\)

- “Residual Sum of Squares”: \(RSS_2 = \sum_{i=1}^n (Y_i - \hat{Y}_i)^2\) where \(\hat{Y}_i\) are the predictions calculated from Model 2

And consider the F-test:

\(H_0\): \(\beta_{k+1} = \beta_{k+2} = ... = \beta_p = 0\)

\(H_a\): at least one of \(\beta_{k+1}\), \(\beta_{k+2}\), …, \(\beta_p\) is non-0

Then the F-test test statistic measures the additional residual error when using Model 2 vs Model 1, while accounting for the complexity of each model. The greater the test statistic, the greater the residuals when we simplify the model (go from Model 1 to Model 2), thus the more evidence we have to reject \(H_0\):

\[ F = \frac{RSS_2 - RSS_1}{RSS_1} \frac{n - (p + 1)}{p - k} \]

Warm-up

DIRECTIONS

- Throughout this activity, test hypotheses at the 0.05 significance level.

- Make all conclusions and interpretations in context.

To explore the relationship of casual bikeshare ridership with the day of week (weekend or weekday), feels like temperature (F), and actual temperature (F), let’s build 3 sample models:

EXAMPLE 1: Nested models

Which of these models are nested in any other?

EXAMPLE 2: “overall” F-tests

The following population model

E[rides | weekend, temp_feel, temp_actual] = \(\beta_0\) + \(\beta_1\) weekendTRUE + \(\beta_2\) temp_feel + \(\beta_3\) temp_actual

is estimated by bike_model_1:

summary(bike_model_1)The “overall” F-test is reported in the bottom line of the summary(). State the hypotheses, p-value, and your conclusion. NOTE: The F-test test statistic is not calculated like the t-test test statistic.

EXAMPLE 3: t-tests for individual model coefficients

State the hypotheses, p-value, and your conclusion about the t-test in the temp_feel row of the summary(). (Similarly, the t-test in the temp_actual row has a p-value of 0.0935 (> 0.05).)

EXAMPLE 4: F-tests for nested models

The following F-test compares bike_model_3 to bike_model_1. State the hypotheses, p-value, and your conclusion.

# Put the smaller model first!!!

anova(bike_model_3, bike_model_1)

EXAMPLE 5: Different angles

A series of models and tests can provide more insight than one model or test alone! What did we learn about the relationship of rides with temp_feel and temp_actual from Examples 3 and 4 combined? Why do you think this happened? What would you do next?

Exercises

The MacGrades dataset contains a sub-sample (to help preserve anonymity) of every grade assigned to a former Macalester graduating class. We have 6414 observations that include sessionID (section), sid (student), sem (semester), iid (instructor), as well as the following variables that we’ll use in our analysis:

grade: the grade obtained, as a numerical value (i.e. an A is a 4, an A- is a 3.67, etc.)dept: department identifier (anonymized)level: course level (e.g. 100-, 200-, 300-, and 600-)enroll: section enrollment

# Load packages & data

library(tidyverse)

MacGrades <- read_csv("https://mac-stat.github.io/data/MacGrades.csv") %>%

mutate(level = factor(level)) # make level a factor variable

head(MacGrades)Exercise 1: Review

Do average grades differ by department? Let’s explore. For simplicity, we’ll focus on just 6 of 40 departments: A, b, B, M, N, q.

Part a

Which is our response / outcome variable: grade or dept?

Part b

Which type of model is appropriate for exploring this relationship: (Normal) linear regression or logistic regression?

Part c

Interpret the sample estimate of the intercept coefficient:

MacGrades %>%

filter(dept %in% c("A", "b", "B", "M", "N", "q")) %>%

with(lm(grade ~ dept)) %>%

summary()Part d

Which department has the lowest average grade and what is that grade? What about the highest average grade?

Part e

Let \(\beta_1\) be the true but unknown deptb coefficient and consider the t-test:

\(H_0\): \(\beta_1 = 0\)

\(H_a\): \(\beta_1 \ne 0\)

How can we interpret \(H_0\)?

- The average grade in Department b is 0.

- The average grade in Department b is different than in Department A.

- The average grade in Department b is not different than in Department A.

Part f

The p-value for this test is 0.589. Interpret the p-value in context. (Your answer should make clear what 0.589 actually means or measures, not just how it compares to 0.05!)

Part g

What’s your conclusion about this hypothesis test?

- We (do / do not) have statistically significant evidence that the average grade in Department b is 0.

- We (do / do not) have statistically significant evidence that the average grade in Department b is different than in Department A.

Exercise 2: F-test and t-tests

Let’s continue to explore the population model of grades vs department:

\[ E[grades | dept] = \beta_0 + \beta_1 deptb + \beta_2 deptB + \beta_3 deptM + \beta_4 deptN + \beta_5 deptq \]

Part a

Recall our research question: Do average grades differ by department? State the relevant hypotheses using notation.

Part b

State the p-value for this test, and what conclusion you make from this p-value.

Part c

Now check out the t-tests for the individual department coefficients. Are any of these statistically significant? What does this mean in context?

Part d

Explain why Parts b and c are not contradictory!

Exercise 3: grades vs enrollment and level

Next, let’s explore the relationship of grades with course enrollment (a quantitative predictor) and level (a categorical predictor with levels 100, 200, 300, 400, and 600). NOTE: We’ll use data on all departments now, not just the 6 used above.

Complete the below model statement of this relationship. For consistency from student to student, put any enroll terms before any level terms. This is the notation you’ll refer to throughout the next exercises!

E[grades | enroll, level] = \(\beta_0\) +

Exercise 4: Some useful and not useful R output

Below are some models and summaries of various relationships of grades with enrollment and level:

grades_model_2 <- lm(grade ~ enroll + level, MacGrades)

grades_model_3 <- lm(grade ~ enroll, MacGrades)

summary(grades_model_2)

summary(grades_model_3)

anova(grades_model_3, grades_model_2)Part a

grades_model_2 is the sample estimate of the model you wrote out in Exercise 3. Interpret the estimated enroll coefficient.

Part b

For classes of the same level, are course grades associated with enrollments? Using your notation from Exercise 3, state the relevant hypotheses that address this question. THINK: Which coefficient(s) is/are relevant?

Part c

What do you need to test these hypotheses?

- some t-test reported in

summary(grades_model_2) - the overall F-test reported in

summary(grades_model_2) - some t-test reported in

summary(grades_model_3) - the overall F-test reported in

summary(grades_model_3) - to F-test comparison of

grades_model_3togrades_model_2reported usinganova()

Part d

Using the approach you identified in Part c, report a p-value and state your corresponding conclusion.

Exercise 5: continuing with grades vs enrollment and level

Let’s continue exploring the relationship of grades with enrollment and level.

Part a

For classes with the same enrollments, are course grades associated with the level of the course? Using your notation from Exercise 3, state the relevant hypotheses that address this question. THINK: Which coefficient(s) is/are relevant?

Part b

What do you need to test these hypotheses?

- some t-test reported in

summary(grades_model_2) - the overall F-test reported in

summary(grades_model_2) - some t-test reported in

summary(grades_model_3) - the overall F-test reported in

summary(grades_model_3) - to F-test comparison of

grades_model_3togrades_model_2reported usinganova()

Part c

Using the approach you identified in Part b, report a p-value and state your corresponding conclusion.

Exercise 6: Guess the p-value

Consider a new model of grades:

grades_model_4 <- lm(grade ~ level, MacGrades)Part a

Using your notation from Exercise 3, state the hypotheses that would be tested by running anova(grades_model_4, grades_model_2). DO NOT YET RUN THIS CODE!

Part b

WITHOUT RUNNING THE anova() CODE: What will be the p-value reported by anova(grades_model_4, grades_model_2)? What’s your reasoning?

Part c

Check your intuition:

anova(grades_model_4, grades_model_2)

Exercise 7: But is it a “good” model?

In the above exercises, you should have concluded that, when controlling for the other, both course enrollments and course level are significantly associated with grades. But are they “good” predictors? Let’s explore grades_model_2 in more depth.

Part a

The relationships of grade with enroll and level are statistically significant, but are they practically significant / contextually meaningful?

Part b

Grades vary from student to student within and across courses. What percentage of this variation is explained by course enrollments and level?

Part c

Putting this all together, what’s your overall conclusion about the relationship here?

Up next

Work on the project!!! Remember to work in the same Google Doc you shared with me for Milestone 2.

Solutions

bikes <- read_csv("https://mac-stat.github.io/data/bikeshare.csv") %>%

rename(rides = riders_casual) %>%

mutate(day_of_week = fct_relevel(day_of_week, c("Mon", "Tue", "Wed", "Thu", "Fri", "Sat", "Sun")))

# Build sample models

bike_model_1 <- lm(rides ~ weekend + temp_feel + temp_actual, bikes)

bike_model_2 <- lm(rides ~ temp_feel + temp_actual, bikes)

bike_model_3 <- lm(rides ~ weekend, bikes)

EXAMPLE 1: Nested models

bike_model_2 and bike_model_3 are nested in bike_model_1.

EXAMPLE 2: “overall” F-tests

summary(bike_model_1)

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = rides ~ weekend + temp_feel + temp_actual, data = bikes)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -1592.49 -252.52 -17.41 181.65 1973.12

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) -1370.647 86.438 -15.857 <2e-16 ***

## weekendTRUE 813.556 36.312 22.405 <2e-16 ***

## temp_feel 11.997 8.712 1.377 0.1689

## temp_actual 15.884 9.459 1.679 0.0935 .

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 443.8 on 727 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.584, Adjusted R-squared: 0.5823

## F-statistic: 340.2 on 3 and 727 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16\(H_0\): \(\beta_1 = \beta_2 = \beta_3 = 0\)

\(H_a\): at least 1 of \(\beta_1, \beta_2, \beta_3\) is not 0

We reject \(H_0\) (p-value < 0.05). We have statistically significant evidence that at least 1 of weekend, temp_feel, or temp_actual are associated with rides.

EXAMPLE 3: t-tests for individual model coefficients

\(H_0\): \(\beta_2 = 0\)

\(H_a\): \(\beta_2 \ne 0\)

We fail to reject \(H_0\) (p-value > 0.05). We do not have statistically significant evidence that when controlling for weekend and temp_actual, there’s an association between rides and temp_feel. That is, if we already know weekend and temp_actual, then temp_feel doesn’t provide significantly more information about rides.

EXAMPLE 4: F-tests for nested models

# Put the smaller model first!!!

anova(bike_model_3, bike_model_1)

## Analysis of Variance Table

##

## Model 1: rides ~ weekend

## Model 2: rides ~ weekend + temp_feel + temp_actual

## Res.Df RSS Df Sum of Sq F Pr(>F)

## 1 729 253858215

## 2 727 143177975 2 110680240 280.99 < 2.2e-16 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1\(H_0\): \(\beta_2 = \beta_3 = 0\)

\(H_a\): at least 1 of \(\beta_2\) and \(\beta_3\) are non-0

We reject \(H_0\) (p-value < 0.05). We have statistically significant evidence that when controlling for weekend status, rides is associated with at least one of temp_feel or temp_actual. That is, even if we already know weekend status, at least one of temp_actual or temp_feel provides significantly new information about rides.

EXAMPLE 5: Different angles

temp_feel and temp_actual aren’t significant when the other is in the model, but at least 1 of these is significantly associated with rides. These predictors are likely multicollinear – thus if we already have one of them in our model, we likely don’t need the other. Our next step would be to take 1 out of the model and see what happens to the significance of the other.

Exercise 1: Review

# Load packages & data

library(tidyverse)

MacGrades <- read_csv("https://mac-stat.github.io/data/MacGrades.csv") %>%

mutate(level = factor(level)) # make level a factor variable

head(MacGrades)

## # A tibble: 6 × 8

## sessionID sid grade dept level sem enroll iid

## <chr> <chr> <dbl> <chr> <fct> <chr> <dbl> <chr>

## 1 session1784 S31185 1.33 M 100 FA1991 22 inst265

## 2 session1785 S31185 3.33 k 100 FA1991 52 inst458

## 3 session1792 S31185 3.33 J 300 FA1993 20 inst235

## 4 session1791 S31185 3.67 J 100 FA1993 22 inst223

## 5 session1794 S31185 2.67 J 200 FA1993 22 inst234

## 6 session1810 S31188 3.67 D 300 FA1997 58 inst150Part a

grade

Part b

(Normal) linear regression (grade is quantitative)

Part c

In department A, the average grade is a 3.5.

MacGrades %>%

filter(dept %in% c("A", "b", "B", "M", "N", "q")) %>%

with(lm(grade ~ dept)) %>%

summary()

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = grade ~ dept)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -3.2386 -0.4261 0.1699 0.4999 0.9039

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 3.5000000 0.4622087 7.572 9.93e-14 ***

## deptb -0.2536066 0.4697248 -0.540 0.589

## deptB -0.2614286 0.4837182 -0.540 0.589

## deptM -0.4039440 0.4633833 -0.872 0.384

## deptN 0.1670000 0.4679507 0.357 0.721

## deptq 0.0001132 0.4639496 0.000 1.000

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 0.6537 on 816 degrees of freedom

## (104 observations deleted due to missingness)

## Multiple R-squared: 0.09843, Adjusted R-squared: 0.0929

## F-statistic: 17.82 on 5 and 816 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16Part d

lowest average grade: department M has an average grade of 3.10 (3.50 - 0.40)

highest average grade: department N has an average grade of 3.667 (3.50 + 0.167)

Part e

- The average grade in Department b is not different than in Department A.

Part f

Remember: p-value = P(data | \(H_0\)) Thus if there were truly no difference in the average grades in Departments A and b, the 0.25 grade-point difference we observed between them in our sample data would be pretty common (with a probability of 0.589).

Part g

We fail to reject \(H_0\) (p-value > 0.05). We (do / do not) have statistically significant evidence that the average grade in Department b is different than in Department A.

Exercise 2: F-test and t-tests

Part a

\(H_0:\) \(\beta_1 = \beta_2 = \beta_3 = \beta_4 = \beta_5\)

\(H_a:\) at least one of \(\beta_1\), \(\beta_2\), …, \(\beta_5\) are non-0

Part b

This is an overall F-test!! The p-value is < 2.2e-16 (which is < 0.05). Thus we have statistically significant evidence of an association between grades and department, i.e. that grades differ between at least 2 departments.

Part c

No, none of the t-tests for the individual department coefficients are statistically significant (they’re all > 0.05). This just means that the average grade in department A doesn’t significantly differ from any other department.

Part d

Though the average grade in department A doesn’t significantly differ from any other department (as indicated by the t-tests), other departments can differ from each other (as indicated by the F-test).

Exercise 3: grades vs enrollment and level

E[grade | enroll, level] = \(\beta_0\) + \(\beta_1\) enroll + \(\beta_2\) level200 + \(\beta_3\) level300 + \(\beta_4\) level400 + \(\beta_5\) level600

Exercise 4: Some useful and not useful R output

grades_model_2 <- lm(grade ~ enroll + level, MacGrades)

grades_model_3 <- lm(grade ~ enroll, MacGrades)

summary(grades_model_2)

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = grade ~ enroll + level, data = MacGrades)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -3.4916 -0.3481 0.1907 0.5162 0.7764

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 3.4091632 0.0219143 155.568 < 2e-16 ***

## enroll -0.0022628 0.0006907 -3.276 0.001058 **

## level200 0.1040873 0.0200701 5.186 2.22e-07 ***

## level300 0.0743387 0.0201066 3.697 0.000220 ***

## level400 0.1118660 0.0320492 3.490 0.000486 ***

## level600 0.6182478 0.1361974 4.539 5.76e-06 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 0.591 on 5703 degrees of freedom

## (437 observations deleted due to missingness)

## Multiple R-squared: 0.01271, Adjusted R-squared: 0.01185

## F-statistic: 14.69 on 5 and 5703 DF, p-value: 2.453e-14

summary(grades_model_3)

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = grade ~ enroll, data = MacGrades)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -3.4529 -0.3871 0.2265 0.5534 0.8448

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 3.4842350 0.0173790 200.485 < 2e-16 ***

## enroll -0.0031336 0.0006683 -4.689 2.81e-06 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 0.5934 on 5707 degrees of freedom

## (437 observations deleted due to missingness)

## Multiple R-squared: 0.003838, Adjusted R-squared: 0.003664

## F-statistic: 21.99 on 1 and 5707 DF, p-value: 2.806e-06

anova(grades_model_3, grades_model_2)

## Analysis of Variance Table

##

## Model 1: grade ~ enroll

## Model 2: grade ~ enroll + level

## Res.Df RSS Df Sum of Sq F Pr(>F)

## 1 5707 2009.8

## 2 5703 1991.9 4 17.904 12.815 2.19e-10 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1Part a

When controlling for course level, the average grade in a course decreases by 0.002 for each additional enrollment (or by 0.02 for each additional 10 enrollments).

Part b

\(H_0:\) \(\beta_1 = 0\)

\(H_a:\) \(\beta_1 \ne 0\)

Part c

- some t-test reported in

summary(grades_model_2)

Part d

The p-value of 0.001058 (reported in the enroll row) is < 0.05. Thus we reject \(H_0\): We have statistically significant evidence that, when controlling for course level, average grades are significantly associated with course enrollments (average grades decrease as enrollments increase).

Exercise 5: continuing with grades vs enrollment and level

Part a

\(H_0:\) \(\beta_2 = \beta_3 = \beta_4 = \beta_5 = 0\)

\(H_a:\) at least one of \(\beta_2, \beta_3, \beta_4, \beta_5\) are not 0

Part b

- to F-test comparison of

grades_model_3togrades_model_2reported usinganova()

Part c

The p-value is 2.19e-10 < 0.05. Thus we reject \(H_0\): We have statistically significant evidence that, when controlling for course enrollment, average grades differ by course level.

Exercise 6: Guess the p-value

grades_model_4 <- lm(grade ~ level, MacGrades)Part a

\(H_0:\) \(\beta_1 = 0\)

\(H_a:\) \(\beta_1 \ne 0\)

Part b

will vary

Part c

The p-value is 0.001058, which is the same as the t-test on the enroll coefficient in summary(grades_model_2). The p-value is the same because they’re testing the same hypotheses!

anova(grades_model_4, grades_model_2)

## Analysis of Variance Table

##

## Model 1: grade ~ level

## Model 2: grade ~ enroll + level

## Res.Df RSS Df Sum of Sq F Pr(>F)

## 1 5704 1995.6

## 2 5703 1991.9 1 3.7491 10.734 0.001058 **

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Exercise 7: But is it a “good” model?

Part a

The enroll predictor doesn’t seem practically meaningful (to me!). There’s a small decrease in average grade per enrollment (0.002) when controlling for level. Given the small class sizes at Mac, this per-enrollment decrease wouldn’t “add up” to a meaningful drop in average grade in most courses.

But the level predictor does seem practically meaningful (to me!). For example, an increase of 0.6 in the average grade from a 100-level to a 600-level course, when controlling for enrollment, is a big jump on the GPA scale.

Part b

Only 1.271%. (This is the R-squared value.)

Part c

It seems that course grades are associated with course level and enrollments, but these factors are not “good” predictors of grades.