# Load useful packages and data

library(tidyverse)

peaks <- read_csv("https://mac-stat.github.io/data/high_peaks.csv") %>%

mutate(ascent = ascent / 1000)

# Check it out

head(peaks)9 Confounding variables

Announcements etc

SETTLING IN

- Put away cell phones (like in your backpack, not face down on your table).

- Sit in your new assigned groups. Re-meet one another!

- Download “09-mlr-confounding-notes.qmd”, open it in RStudio, and save it in the “Activities” sub-folder of the “STAT 155” folder.

WRAPPING UP

- Upcoming due dates:

- Tuesday = PP 3 & CP 8

- Thursday = CP 9 & Quiz 1 revisions by the start of class.

- Continued reminders

- You should have already started PP 3 :)!

- If you don’t finish an activity during class, you should complete it outside of class and check the online solutions!

- Study on an ongoing basis, not just right before quizzes!

By the end of this lesson, you should be familiar with:

- confounding variables

- how to control for confounding variables in our models

- how to represent the role of confounding variables using causal diagrams

Required video

- Confounding (and other causal diagrams)

- Required material: Watch from 0:00 - 6:54.

- Optional but important material: 6:55 - end.

Optional

- Read: Section 3.9.2 in the STAT 155 Notes

References

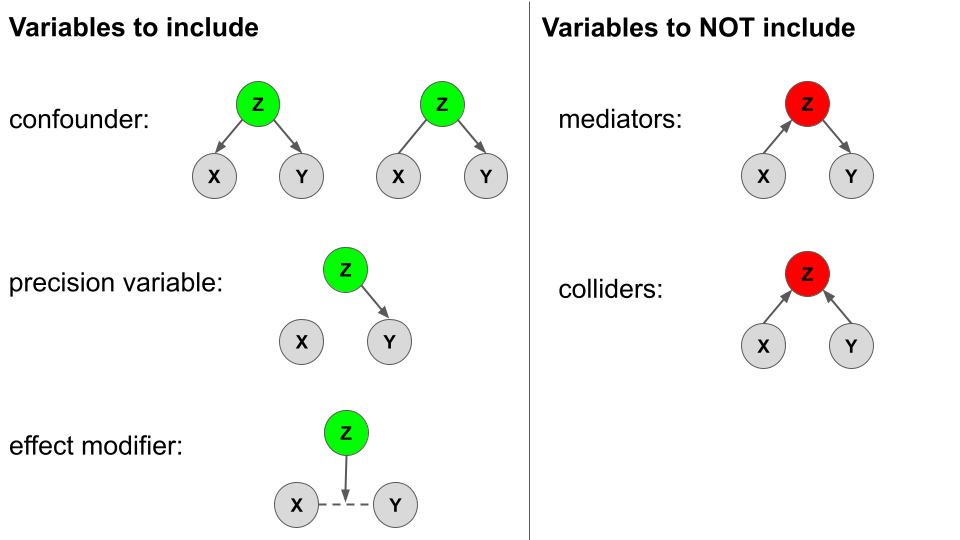

Types of variables in an analysis. First:

- Y = the response variable or outcome of interest

- X = the predictor of interest

When exploring the relationship of Y with X, there are various types of other variables Z. We will largely focus on CONFOUNDERS though it’s good to contrast these with other types!!!

Variables to INCLUDE in our model

\[E[Y|X, Z] = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X + \beta_2 Z\]

- confounders

- Z is a confounder if…

- it is causally associated with both Y and X; or

- it is causally associated with Y, and just associated (not causally) with X

- Failing to adjust for Z leads to an incorrect conclusion about the relationship between Y and X.

- Z is a confounder if…

- precision variable

- Z is a precision variable if it is causally associated with Y, but not associated* (not causally) with X.

- We don’t have to include Z, but it can provide more precise info about the relationship between Y and X, and improve predictions of Y.

- effect modifier

- Z is an effect modifier if it has an effect on the relationship between Y and X.

- We can include Z as an interaction term.

Variables to NOT include in our model

- mediator

- Z is a mediator if it is causally associated with Y and caused by (is the result of ) X.

- Including Z in our model can make it harder to estimate the effect of X on Y – it can attenuate (or even eliminate) the estimated association.

- collider

- Z is a collider if it is caused by Y and caused by X.

- Including Z in our model can introduce bias. For example, it can make it look like there’s an association between Y and X even if one doesn’t exist!

In pictures: Causal diagrams or “directed acyclic graphs” (DAGs)

Warm-up

EXAMPLE 1: Review

Let’s revisit the peaks data:

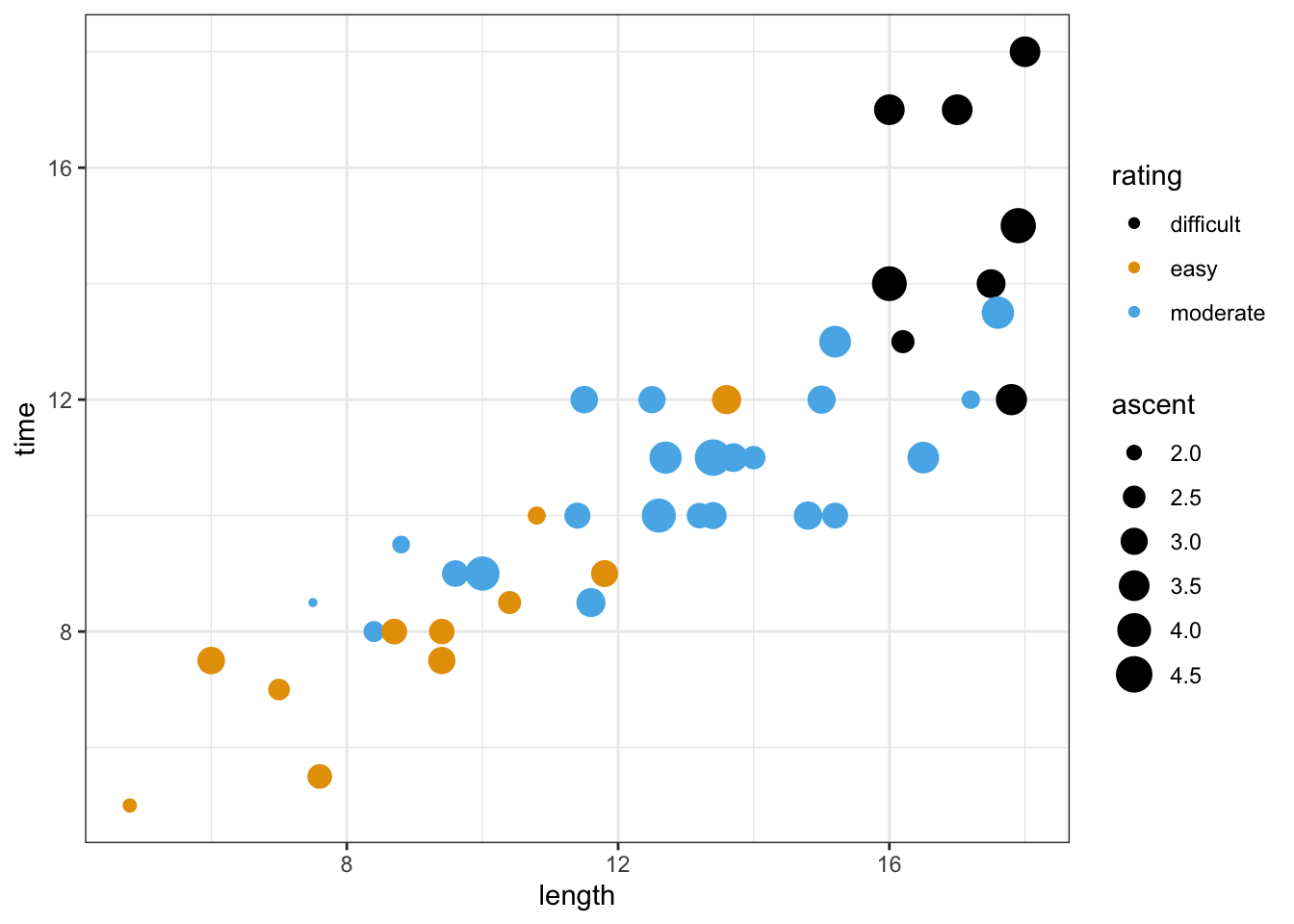

Our goal is to explore the relationship of the time (in hours) that it takes to complete a hike with the hike’s length (in miles), vertical ascent(in 1000s of feet), and rating (easy, moderate, or difficult).

# Modify this code to ATTEMPT to visualize this relationship

peaks %>%

ggplot(aes(y = time, x = length, ___ = ascent, ___ = rating)) +

geom_point()# BONUS: visualize this in "3D"

library(plotly)

peaks %>%

plot_ly(x = ~ascent, y = ~length, z = ~time, color = ~rating,

type = "scatter3d",

mode = "markers",

marker = list(size = 5, colorscale = "Viridis"))Below is a model of this relationship:

peaks_model <- lm(time ~ length + ascent + rating, data = peaks)

summary(peaks_model)Thus the estimated model formula is:

E[time | length, ascent, rating] = 6.511 + 0.459 length + 0.187 ascent - 3.169 ratingeasy - 2.477 ratingmoderate

Interpret the length and ratingeasy coefficients by using the following general strategy: When interpreting a coefficient for variable X, compare two hikes (cases) whose values of X differ by 1 but who are identical for all other variables.

Interpreting the coefficient \(\beta_Q\) for a quantitative variable Q

Holding all other variables in the model constant, each 1-unit increase in Q is associated with \(\beta_Q\) change (increase or decrease) in the expected / average value of Y.

Interpreting the coefficient \(\beta_C\) for an indicator variable on category C

Holding all other variables in the model constant, the expected / average value of Y for the category C is \(\beta_C\) higher/lower than that of the reference category.

EXAMPLE 2: Confounders

In exploring the relationship of Y with our primary predictor of interest X, we may want to / need to adjust for potential confounding variables Z. For example:

- Y = recovery time from a severe cold

- X = treatment, oral medicine or a shot / injection (received at doctor’s office)

A potential confounder is:

- Z = severity of cold symptoms

Explain why Z might be a confounder and draw an appropriate causal diagram, i.e. directed acyclic graph (DAG).

Let Z be a potential confounding variable in the relationship between Y and X.

- Randomized controlled trials / experiments

- We can adjust or control for Z by randomly assigning patients to one of the 2 treatment groups.

- In this case, we can draw causal conclusions (correlation implies causation).

- This is great! But we can’t always run an experiment / trial…

- Observational studies

- Unlike experimental data, observational data is collected without interfering with the study subjects.

- The saying “correlation does not imply causation” stems from unmeasured / unaccounted for confounding in observational studies.

- We can adjust or control for Z by including it in our model of Y vs X.

- This allows us to only assess the relationship between Y and X among groups with the same Z value, thus “removing” the issue of confounding.

- Being able to control for confounders without running an experiment is one of the superpowers of multiple linear regression.

Exercises

Research question: Is there a wage gap, hence possibly discrimination, by marital status among 18-34 year olds?

To explore, we’ll revisit the cps data with employment information collected by the U.S. Current Population Survey (CPS) in 2018:

# Import data

cps <- read_csv("https://mac-stat.github.io/data/cps_2018.csv") %>%

filter(age >= 18, age <= 34) %>%

filter(wage < 250000)

# Check it out

head(cps)Recall that a simple linear regression model of wage by marital suggests that single workers make $17,052 less than married workers, on average:

wage_model_1 <- lm(wage ~ marital, data = cps)

coef(summary(wage_model_1))That’s a big gap!! BUT this model ignores important confounding variables that might help explain this gap.

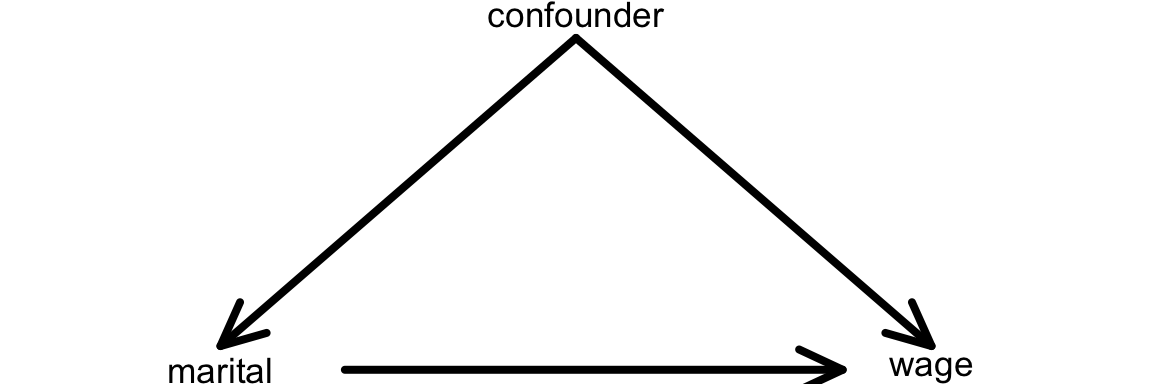

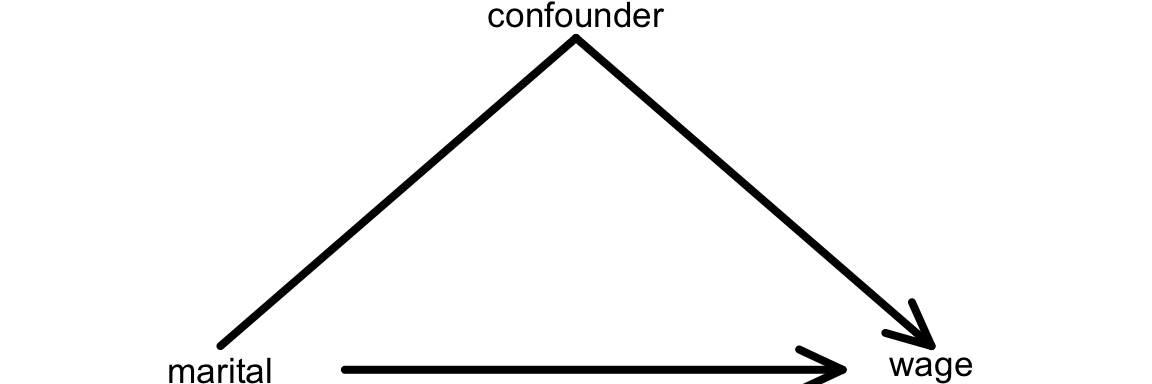

Exercise 1: Confounders

Recall: One definition of a confounding variable is one that

- is a cause of the response / outcome variable (

wage); AND - is a cause of the predictor of interest (

maritalstatus)

We can represent this idea with a causal diagram:

Another definition of a confounding variable is one that

- is a cause of the response variable (

wage) - is associated with the predictor of interest (

maritalstatus), but…- is not a cause of the predictor of interest

- is not caused by the predictor of interest

We can represent this idea with a causal diagram:

QUESTION: Name at least 2 potential confounders in exploring the relationship of wage with marital status.

Exercise 2: How & why do confounders bias results?

Unaccounted-for confounders can be a source of bias in our models. When we ignore them, we often over- or under-estimate the true underlying relationship between a predictor X and response variable Y. To explore why this is important, let’s first look at how our focal predictor marital is associated with our response variable, wage:

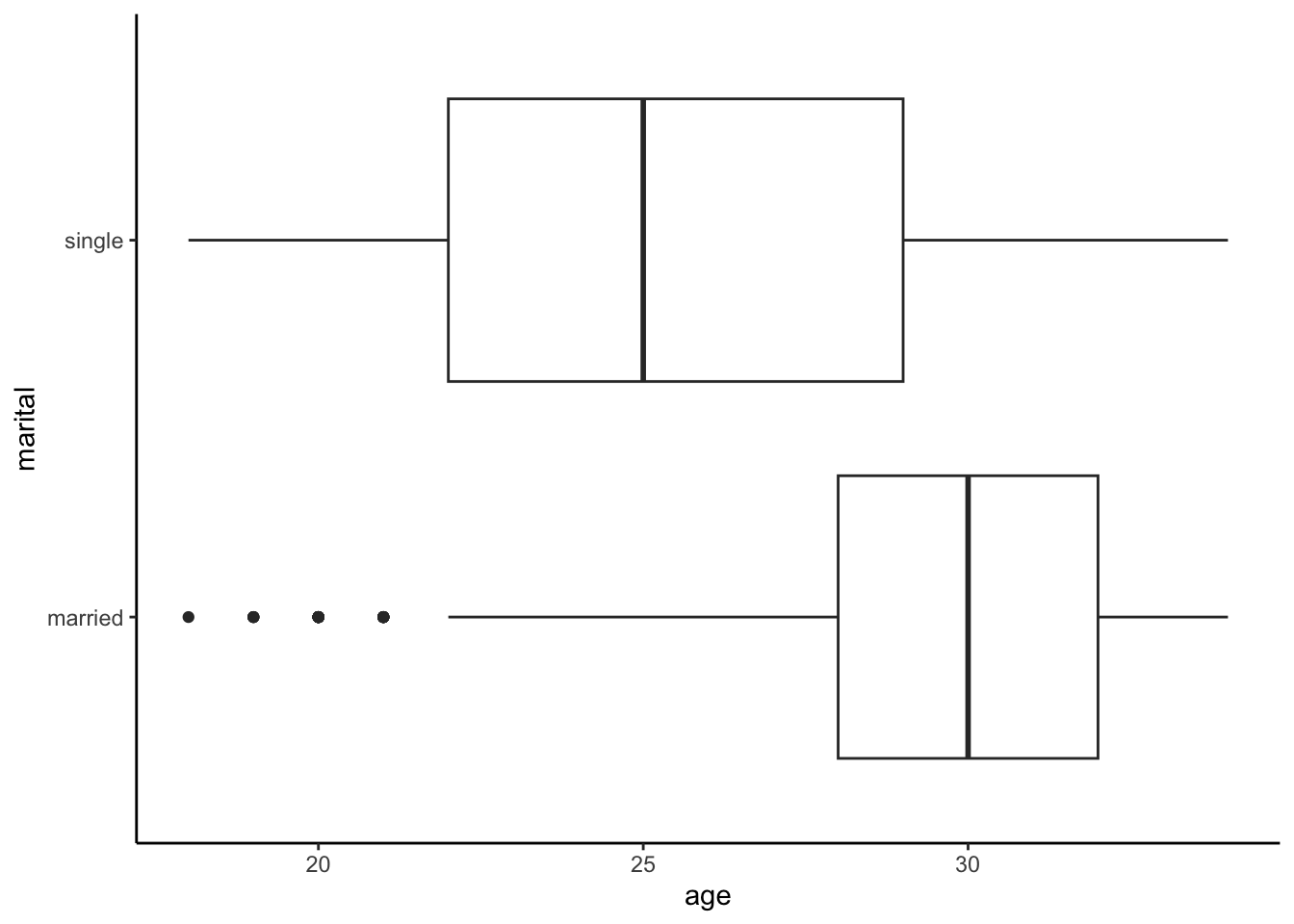

cps %>%

ggplot(aes(x = marital, y = wage)) +

geom_boxplot()Next, consider age as a potential confounder (Z). The below plot shows how age (Z) is associated with marital status (X). The results make sense: the older a person is, the more likely they are to be married!

cps %>%

ggplot(aes(x = age, y = marital)) +

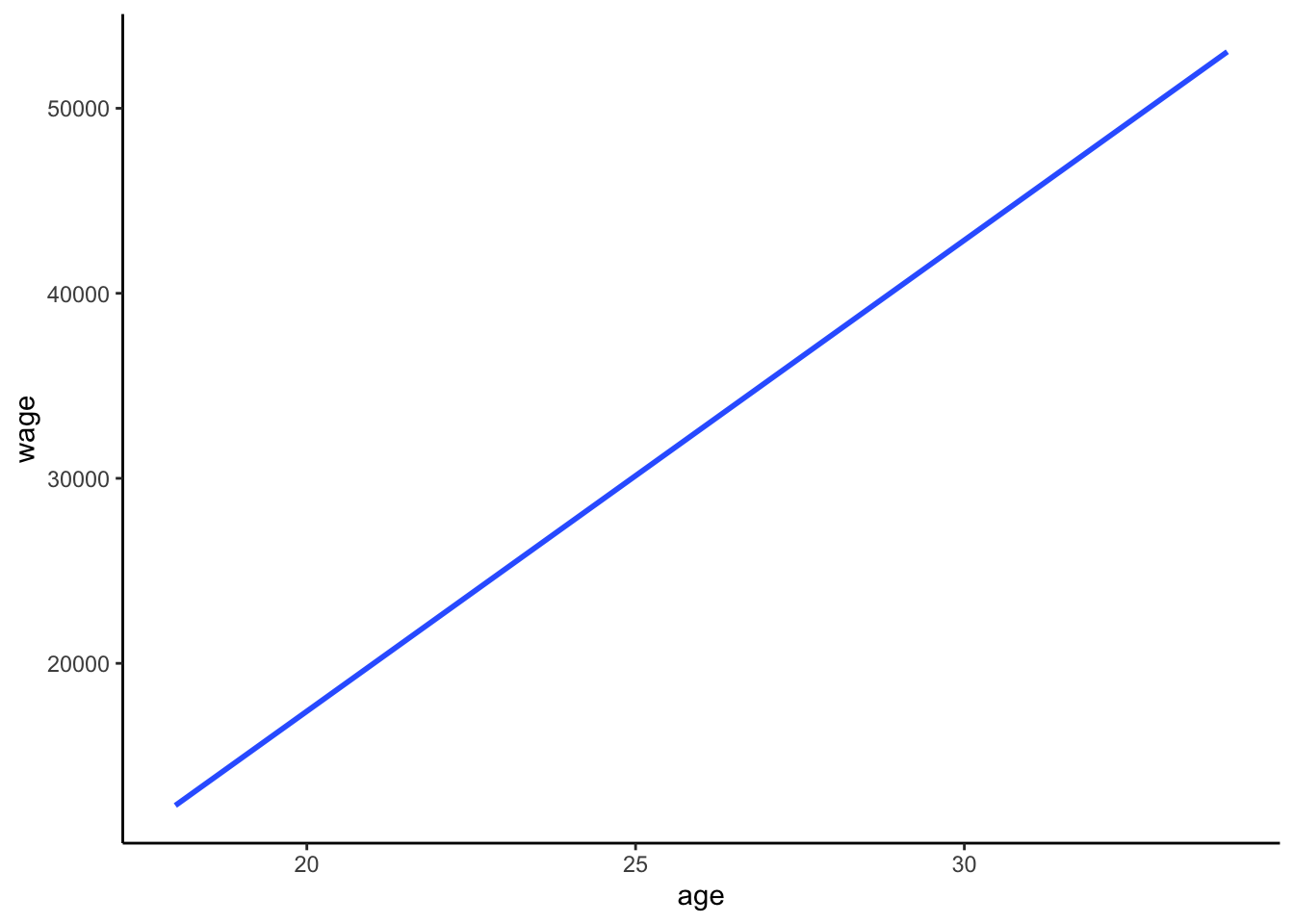

geom_boxplot()Similarly, we can show how age (Z) is associated with wage (Y): The results make sense: older people who have been in the workforce longer typically earn more!

cps %>%

ggplot(aes(x = age, y = wage)) +

geom_smooth(method = "lm", se = FALSE)Let’s now revisit our initial plot of the relationship between marital status and wages:

cps %>%

ggplot(aes(x = marital, y = wage)) +

geom_boxplot()Since we now know that age (Z) is associated with both being married (X) and higher wages (Y), we know that this plot doesn’t tell the full story. People who are married could simply be earning higher wages because they tend to be older, not necessarily because they are married! Age is therefore a confounder in the relationship between marital status and wages.

Exercise 3: Controlling for confounders

The exercise above illustrates that it is important to control or adjust for age when trying to understand the actual causal relationship between marital status and wage. To this end, we’ll have to consider that our cps data was observational, not collected via a randomized trial or experiment. If we had collected the cps data via an experiment, we would have been able to control for age in our exploration of wage vs marital status. BUT what might that experiment look like?!? (Hence why are observational data so common in practice?!?) Discuss with your group.

Exercise 4: Age

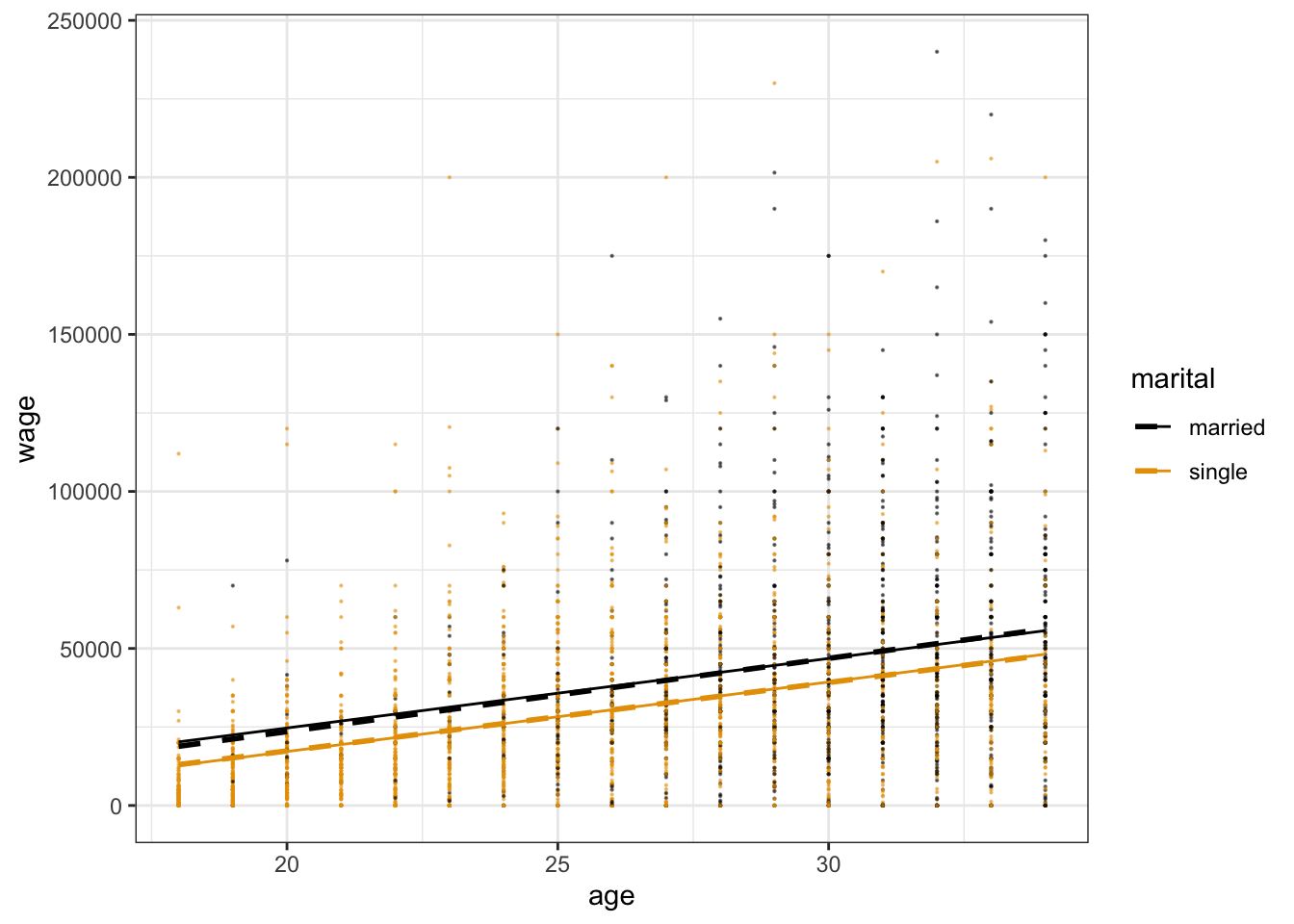

We’re in luck. Even though our cps data is observational, we can control / adjust for age and other confounding variables in the relationship between wage and marital status by including them in our model! That’s one of the superpowers of multiple linear regression. Let’s start by just including age:

# Construct the model

wage_model_2 <- lm(wage ~ marital + age, cps)

coef(summary(wage_model_2))Part a

Fill in the code below to visualize this model: NOTE: The geom_line() layer adds in trend lines from our actual model whereas geom_smooth() would draw the model that uses “interaction terms” (which we’ll learn about next class).

cps %>%

ggplot(aes(y = ___, x = ___, color = ___)) +

geom____(size = 0.1, alpha = 0.5) +

geom_line(aes(y = wage_model_2$fitted.values))Part b

Suppose 2 workers are the same age, but one is married and one is single. By how much do we expect the single worker’s wage to differ from the married worker’s wage? (How does this compare to the $17,052 marital gap among all workers?)

Part c

Multiple choice: How can we interpret the maritalsingle coefficient?

- The average wage is $7500 less for single workers than married workers.

- When controlling for (“holding constant”) age, the average wage is $7500 less for single workers than married workers. That is, among workers of the same age, single workers make $7500 less than married workers on average.

Exercise 5: More confounders

Let’s control for even more potential confounders! Model wages by marital status while controlling for age and years of education:

wage_model_3 <- lm(wage ~ marital + age + education, cps)

coef(summary(wage_model_3))Part a

With so many variables, this is a tough model to visualize. If you had to draw it, how would the model trend appear: 1 point, 2 points, 2 lines, 1 plane, or 2 planes? Explain your rationale. Hint: Pay attention to whether your predictors are quantitative or categorical.

Part b

Recall our research question: Is there a wage gap, hence possibly discrimination, by marital status? Given this question, which coefficient is of primary interest? Interpret this coefficient.

Part c

Interpret the two other coefficients in this model.

Exercise 6: Even more

Let’s control for another potential confounder, the job industry in which one works (categorical):

wage_model_4 <- lm(wage ~ marital + age + education + industry, cps)

coef(summary(wage_model_4))If we had to draw it, this model would appear as 12 planes! The original plane explains the relationship between wage and the 2 quantitative predictors, age and education. Then this plane is split into 12 (2*6) individual planes, 1 for each possible combination of marital status (2 possibilities) and industry (6 possibilities).

Part a

Interpret the main coefficient of interest for our research question.

Part b

When controlling for a worker’s age, marital status, and education level, which industry tends to have the highest wages? The lowest? Provide some numerical evidence.

Exercise 7: Biggest model yet

Build a model that helps us explore wage by marital status while controlling for: age, education, job industry, typical number of work hours, and health status. Store this model as wage_model_5 and report a model summary table.

Exercise 8: Reflection

Take two workers – one is married and the other is single. The models above provided the following insights into the difference in expected wages for these two people:

| Model | Assume the two people have the same… | Wage difference |

|---|---|---|

wage_model_1 |

NA | -$17,052 |

wage_model_2 |

age | -$7,500 |

wage_model_3 |

age, education | -$6,478 |

wage_model_4 |

age, education, industry | -$5,893 |

wage_model_5 |

age, education, industry, hours, health | -$4,993 |

Part a

Though not the case in every analysis, the marital coefficient got closer and closer to 0 as we controlled for more confounders. Explain the significance of this phenomenon, in context. What does it mean?

Part b

Do you still find the wage gap for single vs married people to be meaningfully “large”? Can you think of any remaining factors that might explain part of this remaining gap? Or do you think we’ve found evidence of inequitable wage practices for single vs married workers?

Exercise 9: A new (extreme) example

For a more extreme example of why it’s important to control for confounding variables, let’s return to the diamonds data:

# Import and wrangle the data

data(diamonds)

diamonds <- diamonds %>%

mutate(

cut = factor(cut, ordered = FALSE),

color = factor(color, ordered = FALSE),

clarity = factor(clarity, ordered = FALSE)

) %>%

select(price, clarity, cut, color, carat)Our goal is to explore how the price of a diamond depends upon its clarity (a measure of quality). Clarity is classified as follows, in order from best to worst:

| clarity | description |

|---|---|

| IF | flawless (no internal imperfections) |

| VVS1 | very very slightly imperfect |

| VVS2 | ” ” |

| VS1 | very slightly imperfect |

| VS2 | ” ” |

| SI1 | slightly imperfect |

| SI2 | ” ” |

| I1 | imperfect |

Part a

Check out a model of price by clarity. What clarity has the highest average price? The lowest? (This should be surprising!)

diamond_model_1 <- lm(price ~ clarity, data = diamonds)

# Get a model summary

coef(summary(diamond_model_1))Part b

What confounding variable might explain these results? What’s your rationale?

Exercise 10: Size

It turns out that carat, the size of a diamond, is an important confounding variable. Let’s explore what happens when we control for this in our model:

diamond_model_2 <- lm(price ~ clarity + carat, data = diamonds)

# Get a model summary

coef(summary(diamond_model_2))

# Plot the model

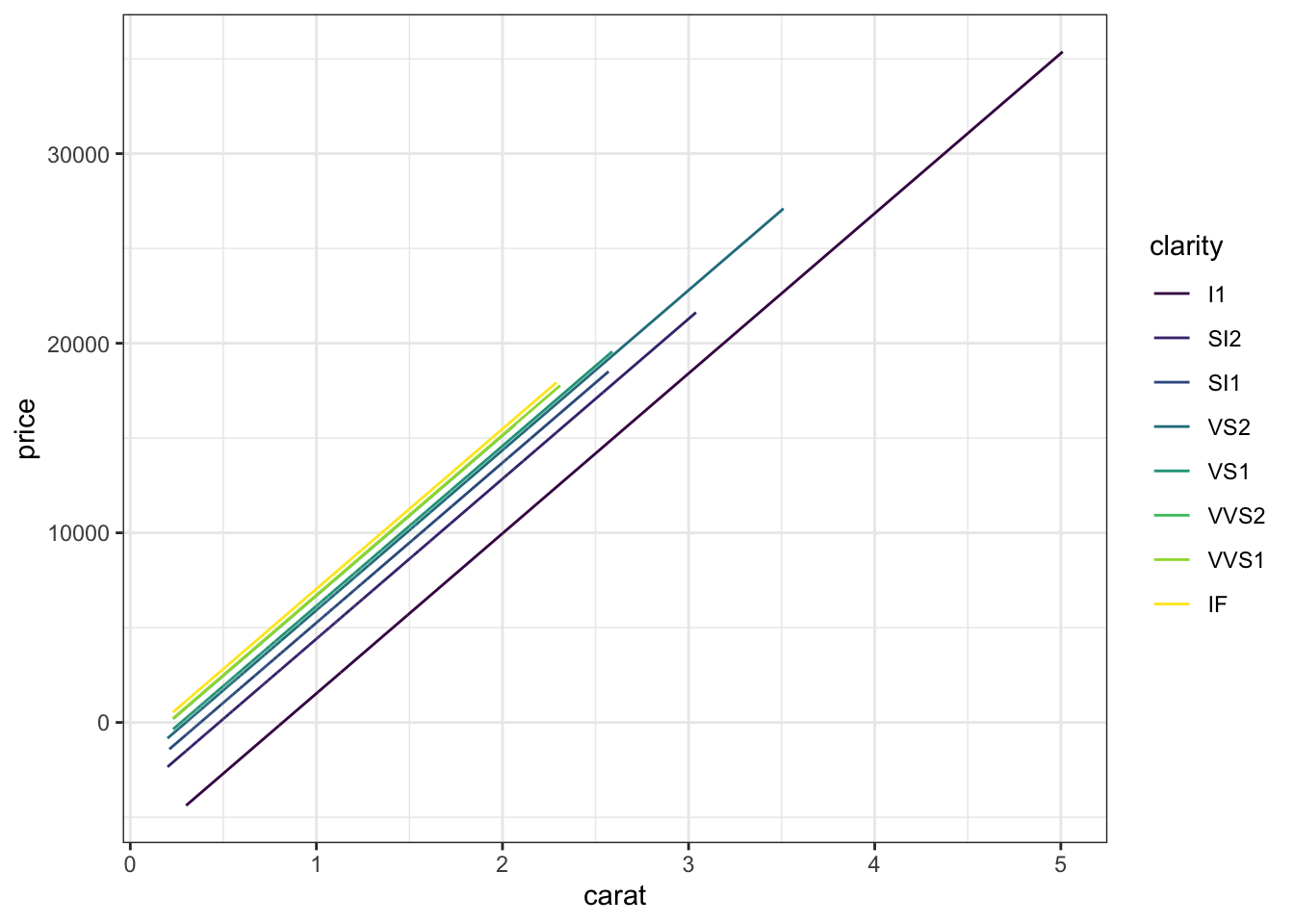

diamonds %>%

ggplot(aes(y = price, x = carat, color = clarity)) +

geom_line(aes(y = diamond_model_2$fitted.values))What do you think now? Which clarity has the highest expected price? The lowest? Provide numerical evidence from the model (not just the visualization).

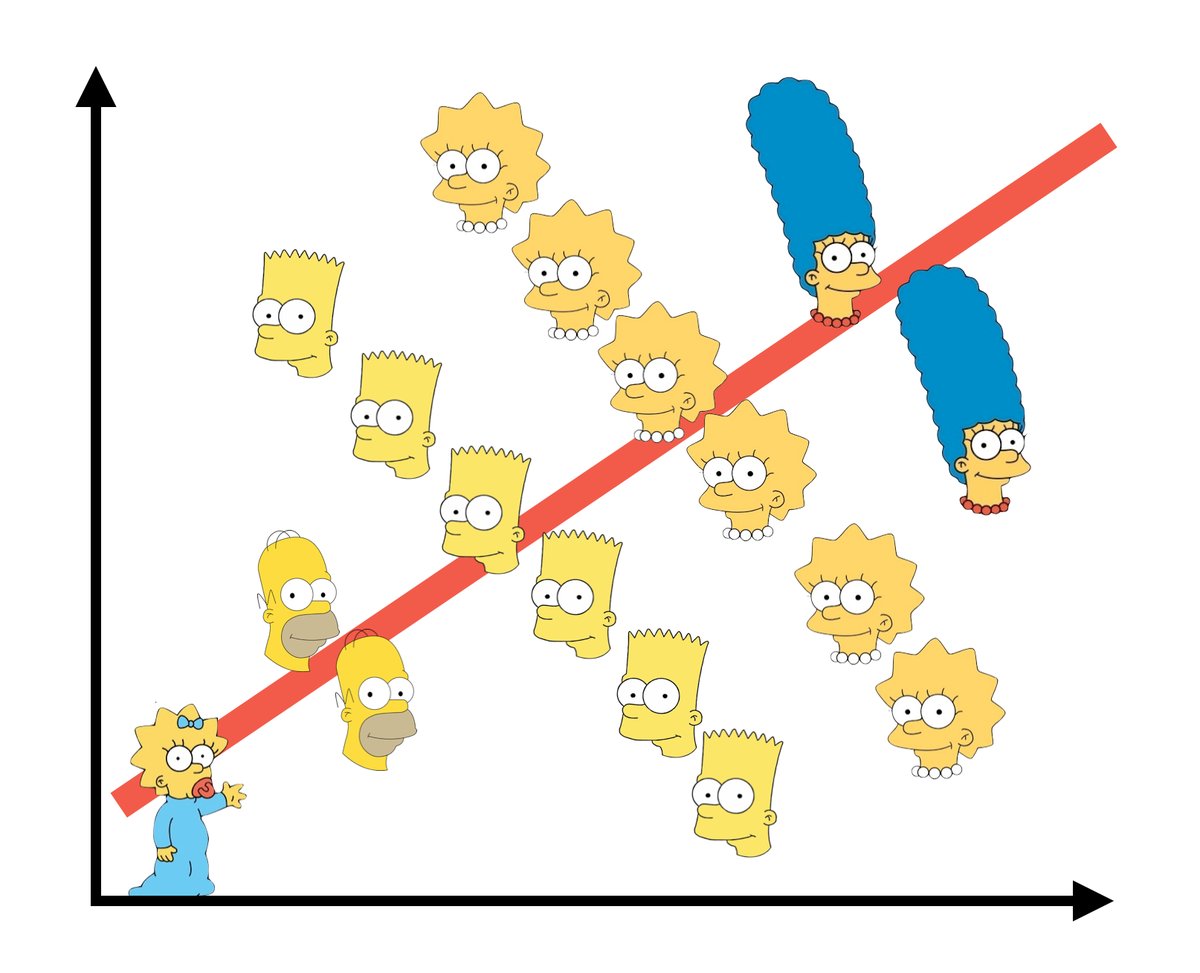

Exercise 11: Simpson’s Paradox

Controlling for carat didn’t just change the clarity coefficients, hence our understanding of the relationship between price and clarity… It flipped the signs of many of these coefficients. This extreme scenario has a name: Simpson’s paradox. Though this paradox is not named for “The Simpson’s”, this graphic does summarize the paradox – though there’s a positive relationship overall, the relationship within each character is negative. Image source: https://jollycontrarian.com/images/e/ed/Simpson_paradox.jpg

CHALLENGE: Explain why this happened and support your argument with graphical evidence. HINTS: Think about the causal diagram below. How do you think carat influences clarity? How do you think carat influences price? Make 2 plots that support your answers.

Exercise 12: Final conclusion

What’s your final conclusion about diamond prices?

Which diamonds are more expensive: flawed ones or flawless ones?

Exercise 13: Reflection

Write a one-sentence warning label for what might happen if we do not control for confounding variables in our model.

Solutions

EXAMPLE 1: Review

# one of many options

peaks %>%

ggplot(aes(y = time, x = length, size = ascent, color = rating)) +

geom_point()

peaks_model <- lm(time ~ length + ascent + rating, data = peaks)

coef(summary(peaks_model))

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 6.5106514 1.62983740 3.994663 2.627176e-04

## length 0.4590819 0.08158314 5.627166 1.465288e-06

## ascent 0.1874830 0.34215350 0.547950 5.866973e-01

## ratingeasy -3.1685224 0.86219113 -3.674965 6.827232e-04

## ratingmoderate -2.4767827 0.61058560 -4.056405 2.177589e-04lengthcoefficient:- Among hikes with the same vertical ascent and challenge rating, each additional mile of the hike is associated with a 0.46 hour increase in completion time on average.

- Holding vertical ascent and challenge rating constant (fixed), each additional mile of the hike is associated with a 0.46 hour increase in completion time on average.

ratingeasycoefficient:- Among hikes with the same length and vertical ascent, the average completion time of easy hikes is 3.2 hours less than that of difficult hikes (reference category).

- Holding constant hike length and vertical ascent, the average completion time of easy hikes is 3.2 hours less than that of difficult hikes.

EXAMPLE 2: Confounders

The severity of symptoms (Z) might influence the treatment type (X) – people with lighter symptoms would likely use oral medicine. The severity of symptoms (Z) might also influence the recovery time (Y) – the lighter the symptoms the quicker the recovery.

Exercise 1: Confounders

age, education, job industry, …

marital vs wage:

cps %>%

ggplot(aes(x=marital, y=wage))+

geom_boxplot()+

theme_classic()

age vs marital:

cps %>%

ggplot(aes(x=age, y=marital))+

geom_boxplot()+

theme_classic()

age vs wage:

cps %>%

ggplot(aes(x=age, y=wage))+

geom_smooth(method="lm", se=F)+

theme_classic()

Exercise 2: How & why do confounders bias results?

just read the exercise :)

Exercise 3: Controlling for confounders

We’d have to get 2 groups that are similar with respect to age, and assign 1 group to get married and 1 group to be single. that would be weird (and unethical).

Exercise 4: Age

# Construct the model

wage_model_2 <- lm(wage ~ marital + age, cps)

coef(summary(wage_model_2))

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) -19595.948 3691.6998 -5.308110 1.184066e-07

## maritalsingle -7500.146 1191.8526 -6.292847 3.545964e-10

## age 2213.869 120.7701 18.331265 2.035782e-71- .

cps %>%

ggplot(aes(y = wage, x = age, color = marital)) +

geom_point(size = 0.1, alpha = 0.5) +

geom_line(aes(y = wage_model_2$fitted.values), size = 0.5)

bonus! adding in the geom_smooth layer:

cps %>%

ggplot(aes(y = wage, x = age, color = marital)) +

geom_point(size = 0.1, alpha = 0.5) +

geom_line(aes(y = wage_model_2$fitted.values), size = 0.5)+

geom_smooth(method="lm", se=F, linetype="dashed")

-$7500

- When controlling for (“holding constant”) age, single workers make $7500 less than married workers on average.

- Among workers of the same age, single workers make $7500 less than married workers on average.

Exercise 5: More confounders

wage_model_3 <- lm(wage ~ marital + age + education, cps)

coef(summary(wage_model_3))

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) -64898.607 4099.8737 -15.829416 2.254709e-54

## maritalsingle -6478.094 1119.9345 -5.784351 7.988760e-09

## age 1676.796 116.3086 14.416777 1.102113e-45

## education 4285.259 207.2158 20.680173 3.209448e-892 planes: There are 2 quantitative predictors which form the dimensions of the plane. The marital status categorical predictor creates 2 planes.

The

maritalsinglecoefficient is of main interest:- Among workers of the same age and years of education, single workers earn $6478 less than married workers.

agecoefficient: Among workers of the same marital status and years of education, each additional year of age is associated with a $1677 increase in salary on average.educationcoefficient: Among workers of the same marital status and age, each additional year of education is associated with a $4285 increase in salary on average.

Exercise 6: Even more

wage_model_4 <- lm(wage ~ marital + age + education + industry, cps)

coef(summary(wage_model_4))

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) -52498.857 7143.8481 -7.3488206 2.533275e-13

## maritalsingle -5892.842 1105.6898 -5.3295615 1.053631e-07

## age 1493.360 116.1673 12.8552586 6.651441e-37

## education 3911.117 243.0192 16.0938565 4.500408e-56

## industryconstruction 5659.082 6218.5649 0.9100302 3.628760e-01

## industryinstallation_production 1865.650 6109.2613 0.3053806 7.600964e-01

## industrymanagement 1476.884 6031.2901 0.2448704 8.065727e-01

## industryservice -7930.403 5945.6509 -1.3338158 1.823603e-01

## industrytransportation -1084.176 6197.2462 -0.1749448 8.611342e-01Among workers of the same job industry, education, and age, single workers make $5893 less than a married worker on average.

highest = construction (because it has the highest positive coefficient), lowest = service (because it has the most negative coefficient)

Exercise 7: Biggest model yet

wage_model_5 <- lm(wage ~ marital + age + education + industry + hours + health, cps)

coef(summary(wage_model_5))

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) -64886.5747 6914.18198 -9.38456275 1.171028e-20

## maritalsingle -4992.7685 1061.84882 -4.70195794 2.687274e-06

## age 1061.1410 115.83503 9.16079518 9.031462e-20

## education 3443.7625 236.12723 14.58435151 1.128646e-46

## industryconstruction 5381.3857 5959.05620 0.90306007 3.665630e-01

## industryinstallation_production 2951.0372 5854.23981 0.50408547 6.142365e-01

## industrymanagement 5107.6364 5782.95334 0.88322283 3.771832e-01

## industryservice -3074.5127 5705.56537 -0.53886207 5.900201e-01

## industrytransportation -207.3439 5940.02074 -0.03490626 9.721567e-01

## hours 732.1340 43.72488 16.74410733 2.340115e-60

## healthfair -7407.7981 2901.71339 -2.55290483 1.072955e-02

## healthgood -2470.8096 1259.44276 -1.96182766 4.987035e-02

## healthpoor -9086.9110 7657.43781 -1.18667774 2.354441e-01

## healthvery_good 292.5278 1020.89213 0.28654136 7.744823e-01

Exercise 8: Reflection

- These confounders explained away more and more of the wage gap between single and married workers.

- Answers will vary. A potential factor that we haven’t considered is a worker’s role within a given industry.

Exercise 9: A new (extreme) example

diamond_model_1 <- lm(price ~ clarity, data = diamonds)

# Get a model summary

coef(summary(diamond_model_1))

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 3677.41676 25.88161 142.086092 0.000000e+00

## clarity.L -1723.35264 98.72036 -17.456913 4.696367e-68

## clarity.Q -428.36467 96.70081 -4.429794 9.450847e-06

## clarity.C 647.87442 83.30820 7.776838 7.567234e-15

## clarity^4 -123.13052 66.72533 -1.845334 6.499443e-02

## clarity^5 804.80570 54.62487 14.733320 4.907171e-49

## clarity^6 -273.65013 47.67881 -5.739449 9.549240e-09

## clarity^7 81.18721 42.01910 1.932150 5.334619e-02highest = SI2, lowest = VVS1

will vary.

Exercise 10: Size

diamond_model_2 <- lm(price ~ clarity + carat, data = diamonds)

# Get a model summary

coef(summary(diamond_model_2))

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) -2977.26896 13.11110 -227.0799509 0.000000e+00

## clarity.L 4216.77507 33.65424 125.2969766 0.000000e+00

## clarity.Q -1931.40632 31.87080 -60.6011296 0.000000e+00

## clarity.C 1005.84704 27.39341 36.7185805 1.486332e-291

## clarity^4 -480.17830 21.94294 -21.8830399 1.089041e-105

## clarity^5 283.94435 17.97527 15.7963882 4.403172e-56

## clarity^6 12.66308 15.68062 0.8075624 4.193461e-01

## clarity^7 198.04828 13.81518 14.3355543 1.597902e-46

## carat 8440.05729 12.65126 667.1315412 0.000000e+00

# Plot the model

diamonds %>%

ggplot(aes(y = price, x = carat, color = clarity)) +

geom_line(aes(y = diamond_model_2$fitted.values))

highest = IF, lowest = I1 (reference category)

This is what we would have expected!

Exercise 11: Simpson’s Paradox

The bigger the diamond the bigger the price:

diamonds %>%

ggplot(aes(y = price, x = carat)) +

geom_point()

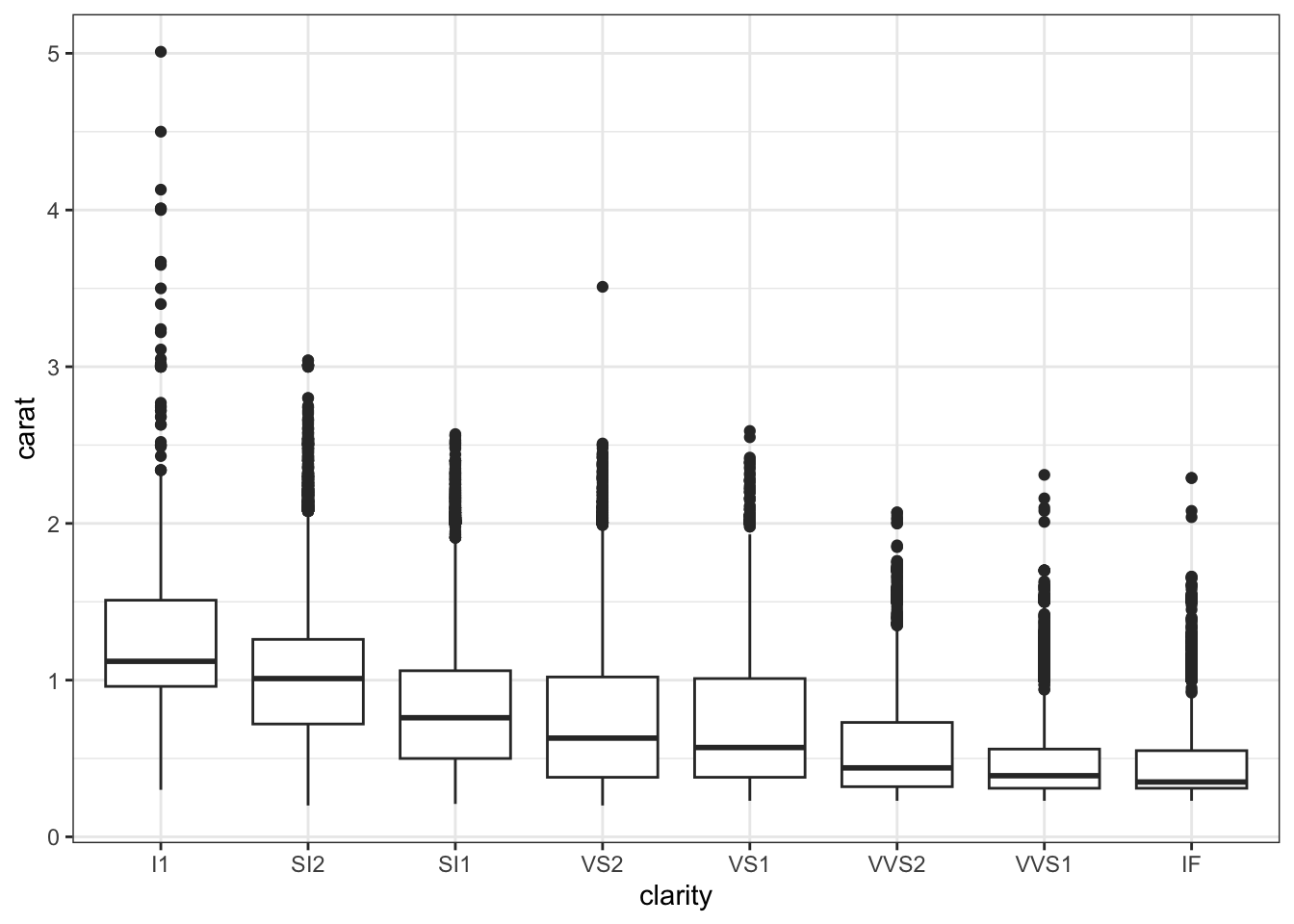

BUT the bigger the diamond, the more flawed it tends to be:

diamonds %>%

ggplot(aes(y = carat, x = clarity)) +

geom_boxplot()

Thus flawed diamonds looked more expensive, but only because they also tend to be bigger (and size is a bigger driver of price).

Exercise 12: Final conclusion

Flawless diamonds are more expensive.